Battle of Pensacola (1814) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Pensacola |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of 1812 | |||||||

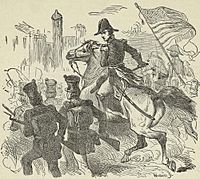

Jackson and his troops entering Pensacola on November 6, 1814 |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

Creek Native Americans |

|||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 4,000 infantry | British: 100 infantry from Royal Marines, Red Sticks and Royal Marine Artillery Unknown artillery and black slaves 1 fort 1 coastal battery Spanish: 500 infantry Unknown artillery 1 fort Creek: Unknown warriors |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| ~7 killed and 11 wounded | ~15 killed or wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Pensacola happened from November 7 to 9, 1814. It was a key event during the War of 1812. In this battle, American forces fought against British and Spanish soldiers. They were also joined by Creek Native Americans and African Americans who supported the British.

General Andrew Jackson led the American troops. They attacked the city of Pensacola in Spanish Florida. This city was controlled by British and Spanish forces. After the fighting, the British and their allies left Pensacola. The remaining Spanish forces then surrendered to General Jackson.

This battle was special because it was the only time during the War of 1812 that fighting happened in Spanish territory. Spain was not happy when the British quickly left the city. A group of five British warships also sailed away from Pensacola.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After Horseshoe Bend

Many Creek people, known as the Red Sticks, fled to Spanish West Florida. This happened after they lost a big battle called the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Because these Creek refugees were in Pensacola, a British captain named George Woodbine came to the city in July 1814.

Captain Woodbine worked with the refugees and the Spanish governor of Pensacola. This allowed the British to set up a military base in Pensacola. They were there from August 23, 1814. At first, they took over Fort San Miguel and the town itself. But the British and Spanish governor had problems. So, the British left the town. They moved to Fort San Carlos and a battery at Santa Rosa Punta de Siguenza.

Gordon's Mission

The armed Creek warriors at Horseshoe Bend made General Jackson worried. He sent Captain John Gordon to check on Pensacola. Jackson wanted to know if the British were using it to arm Native Americans who were against the United States.

When Captain Gordon arrived in Pensacola, he saw the British flag flying at the fort. He also saw British officers training and arming Creek warriors. Gordon's son-in-law, Felix Zollicoffer, later wrote about this trip. He said Gordon traveled 300 miles alone through the forest. He avoided different Native American groups. Gordon brought back important information to General Jackson. This information was about the Spanish forts and how Spain was helping the British and Native Americans. This report helped Jackson decide to attack Pensacola.

Preparing for Battle

General Jackson planned to force the British out of Pensacola. After that, he wanted to march to New Orleans. He knew he needed to defend New Orleans from a possible British attack. Jackson's army had fewer soldiers because some had left. So, he had to wait for Brigadier General John Coffee and his volunteer soldiers.

Jackson and Coffee met in Alabama. Jackson gathered an army of up to 4,000 men. They started marching towards Pensacola on November 2. They arrived on November 6. The British and Spanish forces in Pensacola had about 100 British soldiers and a coastal battery. They also had about 500 Spanish soldiers. There were also an unknown number of British and Spanish artillery troops and Creek warriors.

Jackson first sent a messenger, Major Henri Piere, to the Spanish Governor Mateo González Manrique. Major Piere carried a white flag, which meant he came in peace. But as he got close to the city, soldiers in Fort San Miguel fired at him. Jackson then sent a second messenger, who was Spanish. Jackson offered to put American soldiers in the forts. These Americans would hold the forts until Spanish troops could take them over. This would show that Spain was neutral in the conflict. However, Governor Manrique said no to this offer.

The Battle

At dawn, General Jackson had 3,000 troops marching into the city. The Americans went around the city from the east. This helped them avoid fire from the forts. They marched along the beachfront. But the sandy beach made it hard to move their cannons.

Even so, the attack continued. In the center of town, British and Spanish soldiers fought back. They had a line of infantry supported by a cannon battery. But the Americans charged forward and captured the battery.

Governor Manrique then appeared with a white flag. He agreed to surrender on any terms Jackson offered, as long as Jackson would spare the town. Fort San Miguel surrendered on November 7. But Fort San Carlos, which was about 14 miles to the west, was still held by the British.

Jackson planned to attack Fort San Carlos the next day. However, the British blew up the fort and left it before Jackson could move on it. The remaining British soldiers left Pensacola. A group of British warships also sailed away. Some Spanish soldiers went with the retreating British forces. They did not return to Pensacola until 1815.

After the Battle

The battle forced the British out of Pensacola. The Spanish were left in control. They were angry at the British. The British had left so quickly after Jackson's attack. They also destroyed the forts and took some of the Spanish soldiers with them.

Jackson thought the British warships that left Pensacola might attack Mobile, Alabama. So, Jackson left Pensacola to the Spanish. He then went to Mobile. When he arrived there, he received urgent requests to go to New Orleans to help defend it.

The American army had very few casualties. About seven soldiers died, and eleven were wounded. The Spanish and British forces had at least 15 soldiers killed or wounded. A British officer, Lieutenant Colonel Edward Nicolls, said no British soldiers died. He believed the Americans had 15 deaths and many more wounded.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Pensacola (1814) para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Pensacola (1814) para niños

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |