Battle of Rowton Heath facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Rowton Heath |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of English Civil War | |||||||

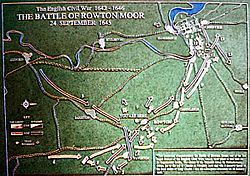

Rowton Moor Battle Site |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Marmaduke Langdale Lord Bernard Stewart † |

Sydenham Poyntz Col. Michael Jones |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 3,500 horse Unknown number of foot |

3,350 horse 500 musketeers |

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 600 killed 900 prisoners |

Unknown | ||||||

The Battle of Rowton Heath, also known as the Battle of Rowton Moor, took place on 24 September 1645. It was a key moment during the English Civil War. In this battle, the Parliamentarian forces, led by Sydnam Poyntz, fought against the Royalists, who were under the direct command of King Charles I.

The battle was a major loss for the Royalists. They suffered heavy casualties, and King Charles I was stopped from helping the city of Chester, which was under siege. Before this battle, King Charles had been trying to join forces with the Marquess of Montrose in Scotland. This was after the Royalists lost the Battle of Naseby.

Even though Charles's efforts to meet Montrose failed, they caused enough trouble that a group managing the war for Parliament, called the Committee of Both Kingdoms, told Sydnam Poyntz to chase the King. Poyntz had about 3,000 cavalry (soldiers on horseback). When Charles learned that Chester, his last important port, was under siege, he marched there. He wanted to help the city's defenders.

On 23 September 1645, Charles ordered 3,000 cavalry, led by Marmaduke Langdale, to camp outside Chester. Charles and 600 other soldiers went into the city. Their plan was to attack the Parliamentarian forces besieging Chester from two sides. Charles wrongly believed that Poyntz had not followed them. However, Poyntz was only about 15 miles behind. He moved to attack Langdale's forces early on 24 September.

Langdale managed to push Poyntz back at first. But the Parliamentarians besieging Chester sent more soldiers. Langdale was then forced to retreat to Rowton Heath, which was closer to Chester. He waited for his own reinforcements there. This extra Royalist force, led by Charles Gerard and Lord Bernard Stewart, could not reach Langdale. Instead, Langdale was attacked by both Poyntz's force and the new Parliamentarian soldiers. After being driven off the field and failing to regroup at Chester, the Royalists retreated as night fell.

The Royalists lost many soldiers. About 600 were killed, including Lord Bernard Stewart, and 900 were taken prisoner. This defeat meant Charles could not help Chester, which then fell to the Parliamentarians on 3 February 1646. Charles left with about 2,400 cavalry. Most of these remaining soldiers were later defeated by Poyntz in an ambush at Sherburn-in-Elmet on 15 October 1645.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

After King Charles I's main army was largely destroyed at the Battle of Naseby on 14 June 1645, the First English Civil War started to go much better for the Parliamentarians. Charles went with his remaining soldiers to Raglan Castle in Wales. He hoped to find new recruits there and cross the Bristol Channel to join George Goring, who was the last Royalist commander with a large army.

But Goring was defeated at the Battle of Langport on 10 July. Also, the new troops in South Wales "fell apart." So, Charles gave up on that plan. Even though he had lost much of Northern England after the Battle of Marston Moor, Charles still had many soldiers in the West of England. Plus, one of his supporters, the Marquess of Montrose, was winning many battles in Scotland.

The Royalist army tried to meet Montrose in Scotland. In early August, Charles took 2,500 soldiers and marched north. But he had to turn back at Doncaster because David Leslie was advancing with 4,000 cavalry. Charles's troops then raided an area called the Eastern Association. They reached Huntington and forced the Parliamentarians who were besieging Hereford to leave.

In response, the Committee of Both Kingdoms ordered Sydnam Poyntz to chase the King. Charles managed to avoid Poyntz's forces. On 18 September, he marched north again. He took 3,500 cavalry, led by William Vaughan and Lord Charles Gerrard, as far as the River Wye at Presteigne. At this point, a messenger told Charles that "part of the outer defenses of Chester were given to the enemy." This forced him to change his plans and march towards Chester.

Chester had been under siege since December 1644. A loose blockade had been set up around the town. With Bristol now taken by the Parliamentarians, Chester was the last port the Royalists controlled. It was very important because it helped them get new soldiers from Ireland and North Wales.

On 20 September 1645, a force of 500 cavalry, 200 dragoons (soldiers who rode horses but fought on foot), and 700 infantry (foot soldiers) attacked the Royalist barricades. This force was led by Michael Jones. The defenders were completely surprised and fell back to the inner city. On 22 September, Parliamentarian cannons began firing at the city. After breaking through parts of the walls, they asked the defenders to surrender, but they refused. The Parliamentarians then attacked in two places. Both attacks were pushed back. In one case, the defenders fought back on foot. In the other, the attackers' ladders were too short to climb the wall.

Even with this success, the attacking Parliamentarian forces grew stronger, while the defenders were tired. So, when Charles and his army arrived on 23 September, they were welcomed with great joy.

The Battle Begins

King Charles's army had 3,500 cavalry. They were split into four groups. The largest group was 1,200 soldiers from the Northern Horse, led by Sir Marmaduke Langdale. There was also Gerard's group of 800 men, who had fought with him in South Wales. Sir William Vaughan had a group of 1,000 soldiers. Finally, there were 200 members of the Life Guards, who were Charles's personal bodyguards, led by Lord Bernard Stewart.

Even though these troops had experience, their numbers were smaller, and their spirits were low because of recent defeats. Charles and Gerard managed to get past the loose Parliamentarian siege around Chester. They took 600 men into the city. The other 3,000 cavalry, led by Langdale, crossed the River Dee at Holt. They camped at Hatton Heath, about five miles south of Chester. The plan was to trap the Parliamentarian besiegers between the two Royalist forces. They thought this would be easy since the besiegers only had 500 cavalry and 1,500 foot soldiers.

The Royalist plan failed because they didn't know about Poyntz and his 3,000 cavalry. They thought he had lost track of them. But they were wrong. As Charles entered Chester, Poyntz's soldiers arrived in Whitchurch, about 15 miles from Chester. When Poyntz heard about the situation, he promised to advance in the morning "with a large group of cavalry." This encouraged the Parliamentarians around Chester to keep fighting.

However, one of Poyntz's messengers was caught by Sir Richard Lloyd. Lloyd immediately sent a message to Charles and Langdale. After a quick meeting, they decided that Gerard's force and the Lifeguards, along with 500 foot soldiers, would advance. Their goal was to either join Langdale or stop Colonel Jones's forces from meeting Poyntz. Charles would stay in Chester and watch the battle from a tower in the city's defenses, which is now known as King Charles' Tower.

Fighting at Hatton Heath

Langdale moved north with 3,000 cavalry. At Miller's Heath on the morning of 24 September, he realized that Poyntz's force of 3,000 was also moving north. Miller's Heath was mostly open land, with the Whitchurch-Chester Road running through it. This road was surrounded by hedges. Langdale placed dragoons and dismounted troopers with carbines (a type of gun) along the hedgerows.

Poyntz's scouts didn't do a good job, so he didn't know Langdale was there until the dragoons started firing at his leading soldiers around 7:00 am. Because Poyntz wasn't ready, his army was stretched out in a long line. The ground was also boggy, making it hard for them to get off their horses. Poyntz had also underestimated the Royalists' strength. He tried attacking with only the troops he had immediately available, thinking they would be enough.

Poyntz was wrong. His leading soldiers got tangled up with the Royalist troops and couldn't make much progress. It took about half an hour of close fighting at the start of the Whitchurch-Chester Road to push the Royalists back. As the Parliamentarians moved onto the open ground to chase the Royalists, a fresh group of Royalist troops attacked them. With no reinforcements, Poyntz had to retreat. In this skirmish, the Parliamentarians lost 20 soldiers, many were wounded, and between 50 and 60 were taken prisoner.

The Royalists lost fewer soldiers, but they were in a difficult spot. They needed more soldiers from Chester to follow up on their success and defeat Poyntz's army. So, Langdale sent Lieutenant Colonel Jeffrey Shakerley to tell Charles and ask for more troops. Shakerley arrived in Chester and delivered his message quickly. But no orders were given for another six hours. Historians think this delay might have been because the Royalist troops were tired. Also, there were rivalries among the Royalist commanders, with Gerard and Digby disagreeing, and others disliking Langdale. King Charles wasn't strong enough to stop these arguments.

However, the Parliamentarians did send help. Around 2:00 pm, the Chester forces sent 350 cavalry and 400 musketeers (soldiers with muskets) under Colonels Michael Jones and John Booth to help Poyntz.

The Main Battle at Rowton Heath

The Royalists in Chester saw the Parliamentarian reinforcements under Jones and Booth advancing. They sent Shakerley to warn Langdale's force. After getting the message, Langdale pulled back closer to Chester. He regrouped his soldiers at Rowton Heath, which was a completely open area. At the same time, the Royalists in Chester began to move. Gerard advanced with 500 foot soldiers and 500 cavalry.

Gerard hoped to attack Jones's force from behind. But the Parliamentarians reacted by sending 200 cavalry and 200 infantry to stop this. Since they had a shorter distance to travel, this Parliamentarian force met Gerard on Hoole Heath. After a confused fight where Lord Bernard Stewart was killed, Gerard's force was stopped from reaching Langdale.

Instead, Jones and Booth joined up with Poyntz. This gave the Parliamentarians a combined force of 3,000 cavalry and 500 musketeers. They were facing a tired Royalist army of about 2,500 cavalry. Around 4:00 pm, Poyntz advanced, with his musketeers firing a full volley (many shots at once) to cover their movement.

Langdale tried to charge back, but the Royalists were quickly outflanked (attacked from the sides). With the Parliamentarian musketeers firing into the back of Langdale's force, the Royalists broke apart. Some escaped by Holt Bridge, and others ran towards Chester. On Hoole Heath, these retreating soldiers met part of Gerard's force. They made a successful counter-attack at first, but then they were forced back to the walls of Chester. There, the retreating cavalry jammed up the streets. This allowed the Parliamentarian musketeers to fire into the confused mass of horsemen, leading to a complete and disorderly retreat.

What Happened Next

The Battle of Rowton Heath was a "major disaster" for King Charles. It's estimated that 600 Royalist soldiers were killed, and 900 were captured. This included 50 members of the Life Guard and Lord Bernard Stewart. Parliamentarian losses were also high, but the exact number is not known. The battle did give Chester a short break from the siege.

Despite this, Charles left the next day with his remaining 2,400 cavalry. He went to Denbigh Castle before moving on to Newark-on-Trent. With Charles gone, Chester was left without more help. The city surrendered to the Parliamentarians on 3 February 1646. The rest of the Royalist cavalry were completely destroyed when Poyntz ambushed them at Sherburn-in-Elmet on 15 October 1645.

Images for kids

-

Phoenix Tower on Chester city walls, where Charles is said to have watched his army lose.