Battle of Schellenberg facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Schellenberg |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the War of the Spanish Succession | |||||||

The Battle of Schellenberg by Jan van Huchtenburg |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Grand Alliance: | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

|

|

||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 5,041-6,000 killed or wounded | 4,000-5,000 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||

The Battle of Schellenberg, also known as the Battle of Donauwörth, happened on July 2, 1704. It was a key moment during the War of the Spanish Succession. This war was fought to decide who would rule Spain after the old king died without an heir. Many European countries formed alliances to support their chosen ruler.

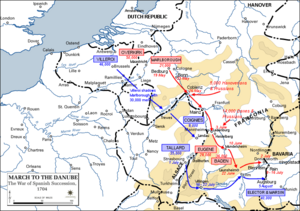

This battle was part of a big plan by the Duke of Marlborough. He wanted to protect Vienna, the capital of Austria, from French and Bavarian armies. Marlborough led his army on a long march from near Cologne to southern Germany. His goal was to convince the Elector of Bavaria to stop supporting France. To do this, the Allies needed a strong base on the Danube river. They chose the town of Donauwörth.

The Elector and his commander, Marshal Marsin, knew what the Allies were planning. They sent Count d'Arco with 12,000 soldiers to defend the Schellenberg hills above Donauwörth. Marlborough decided to attack quickly instead of a long siege. After two tries, the Allied forces finally broke through. The battle lasted only two hours. Even though the Allies won, they couldn't immediately force the Elector to change sides. The war continued, leading to the even bigger Battle of Blenheim later that month.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

The Battle of Schellenberg was part of a larger plan in 1704. The goal was to stop the French and Bavarian armies from attacking Vienna. This city was the capital of Austria. The Duke of Marlborough started his long march on May 19. He traveled about 250 miles (400 km) from Bedburg near Cologne. His target was the Elector of Bavaria and Marshal Marsin's army.

Marlborough tricked the French generals at first. They thought he was heading to other areas in the north. But the Elector of Bavaria guessed correctly that his own land was the real target. This was on June 5.

The Holy Roman Emperor Leopold I wanted the Elector of Bavaria to rejoin his side. The Elector had switched to support King Louis XIV. Marlborough believed the best way to get Bavaria back was to invade. He hoped to make the Elector change sides before more French soldiers arrived. By June 22, Marlborough's army joined with forces led by the Margrave of Baden. Together, they had almost 80,000 soldiers.

The French and Bavarian army was smaller. Many of the Elector's troops were spread out in garrisons. But his situation was not hopeless. If he could hold out for a month, French reinforcements would arrive. These would be led by Marshal Tallard.

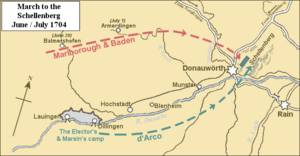

After the Allies joined forces, the Elector and Marsin moved their 40,000 troops. They went to a strong camp between Dillingen and Lauingen. This camp was on the north side of the Danube. The Allied commanders didn't want to attack such a strong position. So, they marched around it towards Donauwörth. Capturing Donauwörth was important. It would give them a bridgehead and a way to get supplies. This would allow them to move into the Elector's lands south of the river.

Preparing for Battle

Schellenberg's Strong Defenses

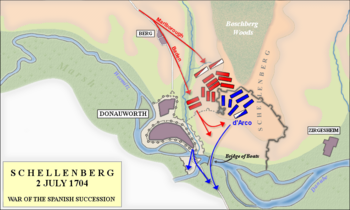

The Schellenberg hills are just northeast of Donauwörth. Donauwörth is a walled town where the Wörnitz and Danube rivers meet. One side of the hill was protected by thick trees. The Wörnitz river and marshes guarded the south and west. This made Schellenberg a very strong place to defend.

However, the top of the hill was flat and open. Its defenses were 70 years old and falling apart. There was an old fort built during the Thirty Years' War. The long eastern side of the hill had good defenses. But the shorter section, where Marlborough attacked, was weaker. It was made quickly with bundles of brushwood covered with thin soil. The western part of the defenses was very steep. It had few defenses but could be protected by fire from the town.

In 1703, Marshal Villars had told the Elector to fix his towns' defenses. He especially mentioned Schellenberg. The Elector had ignored this advice. But when Donauwörth was threatened, Count d'Arco was sent to strengthen the position. He had 12,000 men, many of them Bavaria's best soldiers. The Schellenberg garrison had 16 Bavarian and seven French infantry groups. They also had nine cavalry groups and 16 cannons. Donauwörth itself was held by a French group and two Bavarian militia groups.

The Armies Move In

On the night of July 1-2, the Allies were camped about 15 miles (24 km) from Donauwörth. Marlborough got an urgent message. Marshal Tallard was marching with 35,000 French troops to help the Franco-Bavarian army. This news made Marlborough decide he couldn't wait for a long siege. He planned a direct attack, even though it would cost many lives.

At 3:00 AM on July 2, the Allied advance guard started marching. Marlborough personally watched the first attack force. It had 5,850 foot soldiers. The Dutch General Johan Wijnand van Goor led this group. Behind them came 12,000 Allied infantry. There were also 35 groups of British and Dutch cavalry. The Margrave of Baden's troops were behind Marlborough's. They had a group of grenadiers ready. In total, the Allies used 22,000 men for this attack.

Marlborough rode ahead to see the enemy's position. He saw them preparing a camp on the other side of the river. This meant the Elector's main army was expected the next day. There was no time to lose. Even though it was still light, his men were far behind. They couldn't attack before 6:00 PM. This left only two hours before dark.

As the Allies marched, work on the defenses of Donauwörth and Schellenberg continued. Count d'Arco worked to fix the old trenches. A French officer, Colonel Jean Martin de la Colonie, wrote that they didn't have enough time to finish.

The Allied cavalry appeared around 8:00 AM. Marlborough's Quartermaster-General, William Cadogan, started marking out land for a camp. This was to make it look like they planned a slow siege. Count d'Arco saw this and was fooled. He went to lunch, thinking he had all day to finish the defenses. But the Allied columns kept marching. By mid-afternoon, they had crossed the Wörnitz river. They planned an immediate attack. Bavarian outposts spotted them. They set fire to nearby villages and ran to sound the alarm. General d'Arco rushed back to Schellenberg and called his men to arms.

The Battle Begins

Marlborough's First Attack

Marlborough knew a direct attack on Schellenberg would be costly. But he believed it was the only way to capture the town quickly. If he didn't take the hill by nightfall, it would become too strong. The main Franco-Bavarian army would also arrive to defend it. A female soldier named Christian Welsh, who disguised herself as a man, remembered the attack. She said, "Our vanguard did not come into sight of the enemy entrenchments til the afternoon; however, not to give the Bavarians time to make themselves yet stronger, the duke ordered the Dutch General Goor... to attack as soon as possible."

General d'Arco put de la Colonie's French grenadiers in reserve on top of the hill. They were ready to fill any gaps in the defenses. But the flat top of the hill offered little protection from Allied cannons. Colonel Blood saw this and fired his artillery at the summit. This caused many casualties among de la Colonie's men. De la Colonie wrote that his coat was covered with brains and blood. Even after losing many men, he kept his regiment in place. He wanted to keep discipline.

There was only enough time to attack the north side of the hill before dark. The attack started around 6:00 PM. It was led by a small group called the 'forlorn hope'. These 80 English grenadiers were meant to draw enemy fire. This would help the commanders see where the enemy was strongest. The main force followed close behind. La Colonie recalled, "The rapidity of their movements, together with their loud yells, were truly alarming." He ordered his drummers to beat charge to drown out the Allied shouts.

As the Allies got closer, they became easy targets. The Franco-Bavarian soldiers fired muskets and grape-shot. Defenders also threw fizzing hand-grenades down the hill. To help their attack, each Allied soldier carried a bundle of fascines (bundles of brushwood). These were to bridge the ditches in front of the defenses. But the fascines were thrown into a dry gully by mistake. This was not the main trench, which was further away. Still, the Allies pushed forward. They fought the Bavarians in fierce hand-to-hand combat. The Elector's Guards and la Colonie's men fought hard. The small wall separating the two sides became a scene of very bloody fighting.

Marlborough's Second Attack

The second attack was also unsuccessful. The English and Dutch soldiers advanced side by side. Their generals led them from the front. They faced another wave of musket fire and grenades. Again, the Allies left many dead and wounded at the enemy's defenses. This included Marshal Count von Limburg Styrum. He had led the second attack. The attacking troops fell back down the hill in confusion.

When the Allies were pushed back a second time, the Bavarian grenadiers charged out. They had bayonets fixed and chased the attackers. But English guardsmen and dismounted cavalry stopped them. They forced the Bavarians back behind their defenses.

Baden's Attack

Marlborough had failed twice to break through. Then he learned that the defenses between the town walls and the hill were lightly guarded. Marlborough's attacks had pulled d'Arco's men away from other parts of the stronghold. This left his left side almost unprotected. The other Allied commander, the Margrave of Baden, also saw this chance. He quickly moved his grenadiers to attack this weak spot.

Crucially, Donauwörth's commander had pulled his men inside the town. He locked the gates. So, he could only fire a few shots from the walls. Baden's Imperial troops easily broke through these weak defenses. They defeated the few soldiers still there. They then formed up at the bottom of Schellenberg. This put them between d'Arco and the town. D'Arco saw the danger. He rushed to get his dismounted French dragoons. He tried to stop the Imperialists marching up the hill. But Baden's grenadiers fired many shots, forcing the cavalry to retreat. This left d'Arco separated from his main force. He headed for the town. According to de la Colonie, he had trouble getting in because the commander hesitated to open the gates.

The Breakthrough

Marlborough knew that Imperial troops had broken through Schellenberg's defenses. So, he launched a third attack. This time, the attackers spread out more. This made d'Arco's men spread their fire, making it less deadly. But the defenders, including la Colonie, were still confident. They didn't know that the Imperialists had broken through their left side. They also didn't know d'Arco had retreated. La Colonie wrote, "We remained steady at our post; our fire was regular as ever, and kept our opponents in check."

Soon, the Franco-Bavarian soldiers on the hill saw Baden's infantry. They were coming from the town. Many officers thought they were reinforcements from Donauwörth. But it quickly became clear they were Baden's troops. De la Colonie wrote, "They [Baden's Imperial grenadiers] arrived within gunshot of our flank about 7:30 in the evening, without our being aware of the possibility of such a thing." Baden's men fired on the surprised defenders. This forced them to turn and face this new threat. Because of this, Marlborough's attacking troops could climb over the now weakly defended wall. They pushed the defenders back to the top of the hill. The enemy finally fell into confusion.

The defenders of Schellenberg were outnumbered. They had fought off the Allied attacks for two hours. But now, under pressure from both Baden's and Marlborough's forces, their strong defense ended. Panic spread through the Franco-Bavarian army. Marlborough sent 35 groups of cavalry to chase the fleeing troops. They cut down enemy soldiers with shouts of "Kill, kill and destroy!" There was no easy way to escape. A bridge over the Danube collapsed under their weight. Many of d'Arco's troops, who couldn't swim, drowned. Others ran through the reeds, trying to avoid the Allied swords. Some headed for a village, hoping to escape to the hills. Only a few Franco-Bavarian groups crossed the Danube by Donauwörth's bridge in some order before darkness fell.

What Happened Next

De la Colonie was one of the few who escaped. But the Elector of Bavaria had lost many of his best soldiers. This greatly weakened his army for the rest of the campaign. Very few of the men who defended Schellenberg rejoined the Elector's army. However, Count d'Arco and his second-in-command, the Marquis de Maffei, did escape. They later fought at the Battle of Blenheim.

Of the 22,000 Allied soldiers, over 5,000 were killed or wounded. This overwhelmed the hospitals Marlborough had set up. Six lieutenant-generals, four major-generals, and 28 other senior officers were among the dead. This shows how dangerous it was for officers leading the attacks. No other battle in the War of the Spanish Succession killed so many senior officers.

The victory brought the usual rewards of war. The Allies captured all the cannons on Schellenberg. They also took all the regimental flags, ammunition, and other valuable items. But the high number of casualties worried some in the Grand Alliance. The Dutch created a victory medal, but it didn't mention the Duke of Marlborough. However, the Emperor wrote to the Duke personally. He praised Marlborough's speed and strength in taking the enemy camp.

The Impact on Bavaria

Marlborough had won a way to cross the Danube. He had also placed his army between the French and Vienna. But after the battle, things slowed down. Marlborough wanted to force the Elector into another battle before Tallard arrived with more soldiers. But the Allied commanders couldn't agree on their next move. This led to a long siege of Rain. The town didn't fall until July 16. Still, Marlborough quickly took Neuburg. With Donauwörth, Rain, and Neuburg, the Allies had enough bridges to move easily.

The Allied commanders then marched to Friedberg. They watched their enemy across the Lech river. They also stopped them from getting supplies from Bavaria. The main goal for the Allies was to get Bavaria to switch sides. Since the Elector was behind his defenses, Marlborough sent his troops into Bavaria. They destroyed buildings and crops. This was to force the Elector to fight or change his loyalty. The Emperor offered the Elector a full pardon and his lands back. But the talks didn't go well.

The destruction in Bavaria led the Elector's wife, Theresa Kunegunda Sobieska, to ask him to leave the French alliance. The Elector did hesitate. But then he heard that Tallard's reinforcements, about 35,000 men, would soon be in Bavaria. This made him determined to keep fighting. Marlborough then increased the destruction in Bavaria. He wrote to a friend that they were "advancing into the heart of Bavaria to destroy the country and oblige the Elector one way or the other to a compliance." This forced the Elector to send 8,000 troops to defend his own property. He kept only a small part of his army to join the French.

Marlborough thought this was a necessary plan. But he also felt it was difficult. He told his wife, Sarah, that it was "uneasy to my nature." He said he would only do it if it was absolutely necessary. He felt bad for the people who suffered because of their leader's choices. Some accounts say the damage was exaggerated for propaganda. But others, like Christian Davies, wrote that the Allies "spared nothing, killing, burning or otherwise destroying whatever we could not carry off."

There are records of the 1704 events in churches in Upper Bavaria. Villages like Viehbach and Bachenhausen also recorded the destruction. When their homes were saved, they promised to hold a special Mass every year. This was to remember their deliverance. This promise can still be seen in the old church in Viehbach.

The Allies had not been able to get enough heavy cannons. This had stopped them from winning completely. They couldn't take Munich or Ulm. The Elector had not been defeated or forced to change sides. Prince Eugene was worried that no big action had followed the Schellenberg victory. He wrote that they had been "burning a few villages instead of... marching straight upon the enemy."

Tallard arrived in Augsburg with French reinforcements on August 5. Eugene was also heading south with 18,000 men. But he had to leave 12,000 troops behind to stop more French reinforcements. Also, the Elector had finally ordered his Bavarian troops to rejoin the main army. So, time was short for the Allies. They had to defeat the French and their allies soon, or all of southern Germany would be lost.

On August 7, the three Allied commanders met. Marlborough, Baden, and Eugene decided on their next plan. Baden suggested besieging Ingolstadt with 15,000 men. They agreed, even though it would make the Allied army smaller. This would give them another major way to cross the Danube.

|

| Selma Burke |

| Pauline Powell Burns |

| Frederick J. Brown |

| Robert Blackburn |