Battle of Valenciennes (1656) facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Battle of Valenciennes |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Franco-Spanish War | |||||||

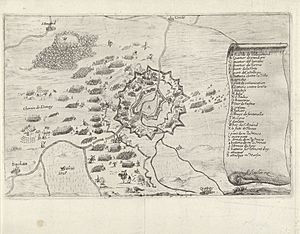

John Joseph of Austria leads the Spanish Army to the victory at the Battle of Valenciennes, by David Teniers II. |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Vicomte de Turenne Maréchal La Ferté (POW) |

John Joseph of Austria Prince of Condé |

||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 24,000-30,000(9,000 engaged) | 22,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

|

6,000-7,500

|

500-1,500 dead or wounded | ||||||

The Battle of Valenciennes was a major fight that happened on July 16, 1656. It took place near the city of Valenciennes in what is now Belgium, during the Franco-Spanish War. The Spanish army, led by John Joseph of Austria, won a big victory against the French troops, commanded by Vicomte de Turenne.

Before this battle, France had been doing well in the war. They had put down some internal rebellions and captured several towns. In early 1656, the French general Turenne planned to attack the city of Tournai. But he found out that the Spanish had strongly reinforced it. So, he decided to besiege Valenciennes instead, a city along the Scheldt river.

The people defending Valenciennes tried to stop the French by flooding the areas around the city. Their strong defense gave the Spanish army time to prepare a rescue mission. In the early hours of July 16, the Spanish forces, led by John Joseph of Austria and Prince of Condé, attacked the French siege lines. The Spanish won, destroying a large part of the French army. Turenne couldn't help his troops because the floods separated their armies.

The Battle of Valenciennes was one of the few defeats Turenne suffered in his long career. It's seen as Spain's last major victory in the 1600s. It also seriously weakened France's military power. Peace talks happened that summer, but they didn't lead to an agreement. The war continued for three more years until the Peace of the Pyrenees in 1659.

Contents

Why the Battle Happened

France and Spain had been fighting since 1635. Spain faced problems like revolts in Catalonia and Portugal in 1640. This allowed France to gain an advantage, especially after the Battle of Rocroi in 1643. However, a peace treaty between Spain and the Dutch Republic in 1648 helped Spain recover. Also, France had its own civil wars, called the Fronde.

By 1652, Spain had won back many lost areas. These included Barcelona and most of Catalonia. They also recaptured important ports like Gravelines and Dunkirk in Flanders. Spain offered peace to France, but the French chief minister, Cardinal Mazarin, refused. He hoped France could recover more.

In 1653, French armies put down the Fronde rebellions. The leader of the Fronde, Prince of Condé, then joined the Spanish side. In 1654, France continued to strengthen its position. They besieged Stenay, a city held by Condé's army. In response, the Spanish and their allies besieged Arras. A French army under Turenne attacked the Spanish lines at Arras and forced them to retreat. This was a French victory, but not a final one.

The Spanish situation got worse in 1655. The French army under Turenne captured several important towns. These included Landrecies, Condé, and Saint-Ghislain. These towns were north of Valenciennes. This put cities like Douai, Bouchain, Valenciennes, and Tournai at risk.

Because of these defeats, King Philip IV of Spain replaced his general in the Spanish Netherlands. He appointed his son, John Joseph of Austria, as the new commander. John Joseph was young but had already won battles in Naples and Catalonia. He was also a good negotiator.

In early 1656, the Spanish army had about 22,000 soldiers. France had more troops and took the lead. Their forces were split into two armies. One had 16,500 men led by Turenne. The other had 9,000 to 10,000 men under Marshal La Ferté. They joined forces and set up their supplies.

The French King Louis XIV wanted to be part of the campaign. Turenne first planned to besiege Tournai. But the Spanish had already sent 4,000 men to reinforce the city. So, Turenne decided to besiege Valenciennes instead. On June 15, his army surrounded the city from one side. The next day, La Ferté's army approached from the other side. Their troops were separated by the Scheldt river.

The Siege of Valenciennes

Surrounding the City

Valenciennes was defended by about 2,000 soldiers and 300 cavalry. They were led by Alexander von Bournonville. About 6,000 armed citizens also helped defend the city. The defenders tried to stop the French siege works. They opened locks and broke dikes to flood the areas around the city. This made it harder for the French to build their siege lines.

The French army surrounded Valenciennes and began building a "circumvallation line." This was a defensive wall to protect their own army from attacks from outside. Turenne placed his troops in certain areas. He set up his main camp where he expected any Spanish relief army to appear.

Marshal La Ferté's army was on the other side of the Scheldt river. A pontoon bridge was built to connect Turenne's army with La Ferté's. La Ferté built four small forts, called redoubts, to stop any rescue attempts. However, he made a mistake by not extending his lines to cover a high area that overlooked his section.

The defenders of Valenciennes kept flooding the land. On June 16, they broke a dike, flooding the marshes. The next day, they blocked a canal, causing more flooding. This made it very difficult for the French to move around. However, the French kept building their bridge over the flooded land. It was finished by June 26.

Preparing for Rescue

Once the French had finished their siege lines, they started digging trenches towards the city's citadel. They also set up cannons to bombard the city. The Spanish defenders made several attacks from the city. These attacks slowed down the French. This gave John Joseph of Austria and Condé time to prepare their rescue mission.

The Spanish army was near Douai. They had about 10,500 to 11,000 infantry and 5,000 to 5,500 cavalry. Condé also had about 5,800 men. On June 27, they moved towards Valenciennes from the south. They set up a fortified camp on a hill called Mont Houy. A smaller group of 4,000 men under the Count of Marsin positioned themselves on the other side of the Scheldt river.

The Spanish forces skirmished with the French, looking for a weak spot. They also set up cannons to bombard the French camps. The French, meanwhile, worked faster on their trenches. By July 1, they were ready to attack a part of the city's defenses called the ravelin of Montoise. The French launched attacks, but the defenders fought back hard.

On July 6, another French attack failed, and they lost many soldiers. However, the next day, the French succeeded in taking a part of the outer defenses. Bournonville, the city's commander, then wrote to John Joseph. He said he couldn't hold out for more than a few more days. On July 14, the Spanish leaders decided to attack the French lines and rescue Valenciennes. The next day, the main Spanish army crossed the Scheldt river to attack La Ferté's army.

The Battle Begins

The Spanish army got ready for battle late on July 15. A small group of 1,000 men stayed at Mont Houy with heavy cannons. Their job was to make it seem like the main Spanish army was still there. The main attack would come from the west, towards the village of Anzin. Marsin was ordered to attack La Ferté's camp from the north as a distraction.

The Spanish army was divided into sections. The right side was led by the Marquis of Caracena. The center was led by the Prince of Ligne. Condé led the left side. The Spanish had about 10,000 infantry and 7,500 cavalry. The French army under Turenne had about 9,000 to 9,500 infantry and 7,500 to 8,000 cavalry. La Ferté had about 6,000 to 6,500 infantry and 3,500 to 4,000 cavalry.

At 2:00 a.m., the Spanish cannons at Mont Houy fired, signaling the attack. Marsin attacked the French lines fiercely, but he was forced to retreat. The main Spanish attack, however, was more successful. Soldiers with grenades led the way. They threw grenades over the French lines and then jumped into the ditches to climb over the defenses.

On the right, the Spanish and Irish soldiers under Caracena took the first and second lines of French defenses. The German soldiers under Condé also succeeded on the left. However, the Walloon and Italian soldiers in the center were stopped by heavy French gunfire. Hundreds of engineers worked to fill the ditches and clear paths for the cavalry. The infantry in the center attacked again and, on their third try, took the second line of defenses.

While the Spanish attacked, Turenne, on the other side of the river, realized what was happening. He quickly sent six infantry regiments to help La Ferté. Meanwhile, La Ferté launched a counterattack with his reserves. But the Spanish soldiers, now joined by their cavalry, pushed them back. Then, Bournonville attacked from inside Valenciennes. The French resistance collapsed.

La Ferté was captured by one of Condé's men. The remaining French soldiers fled in chaos. Hundreds of them drowned trying to cross the Scheldt river. Only about 2,500 men from La Ferté's army managed to escape. They couldn't join Turenne and had to find shelter in the town of Condé. Within two hours, the Spanish cavalry met up with the Valenciennes defenders.

By 6:00 a.m., Turenne knew the battle was lost. He ordered his troops to leave their camps, abandoning their cannons and supplies. The Spanish cavalry chased the retreating French. Turenne managed to regroup his army by the evening. The French lost between 7,000 and 8,000 men, including 2,500 to 3,000 prisoners. They also lost 46 cannons and huge amounts of supplies. The Spanish army lost about 500 men during the battle and 200 to 300 during the siege.

What Happened Next

News of the Spanish victory reached Brussels the same day. Public celebrations were ordered. In Madrid, King Philip IV heard the news on August 1. He believed it was a miracle from God. In Paris, King Louis XIV and his court were very sad.

The battle greatly improved John Joseph's reputation. He then moved to besiege Condé. Cardinal Mazarin told Turenne not to lose Condé and Saint-Ghislain. But Turenne's army was smaller, and the Spanish position was too strong. John Joseph did not stop his siege, and on August 18, the French soldiers in Condé surrendered to the Spanish.

Both sides began serious peace talks in Madrid that summer. France offered to stop supporting Portugal's rebellion against Spain. They also offered to leave their positions in Catalonia and return some towns. Spain agreed to recognize French control over some areas. However, the talks failed. Mazarin refused to give Prince Condé his old positions back. Also, King Philip IV refused to let his daughter marry Louis XIV.

In military terms, France lost thousands of experienced soldiers at Valenciennes. This meant France could no longer launch quick and decisive campaigns. The defeat also caused financial problems for France. On March 23, 1657, the Spanish army took Saint-Ghislain. Turenne tried to besiege Cambrai, but Prince Condé rescued its defenders. Only when France allied with England and received 6,000 English soldiers did they start to make some gains again.

Awards and Honors

Many noblemen who fought for Spain at Valenciennes received awards. Philippe-François d'Arenberg was promoted to general. Bournonville, who defended Valenciennes, was given the title of prince by King Philip IV. However, a common soldier named Francisco de Meneses, who played a key role in defending Valenciennes, did not receive much recognition from the Spanish court.

Remembering the Battle

The Battle of Valenciennes became a popular subject for poems, songs, artworks, and coins. Flemish artists like David Teniers II and Pieter Snayers painted scenes of the battle. Teniers, who was a court painter, showed the rescue in a large painting. It included the army commanders like John Joseph, Prince Condé, and the Marquis of Caracena. John Joseph is shown on horseback, looking like a strong leader.

In literature, students at Jesuit colleges wrote poems about the siege and battle. A play praising John Joseph of Austria was performed in Brussels. Medals were also made to celebrate the victory. A medallist from Brabant created gold, silver, and bronze medals.

From a religious point of view, some people believed God helped the Spanish. They pointed out that the French siege began on June 15, the Feast of Corpus Christi, which they saw as a disrespectful act. The Spanish army, on the other hand, attacked on the day the Eucharistic Miracle of Brussels was celebrated. John Joseph ordered prayers and ceremonies for the success of the rescue. This idea of divine help is shown in Teniers' painting and on the medals.

See also

In Spanish: Batalla de Valenciennes (1656) para niños

In Spanish: Batalla de Valenciennes (1656) para niños