Betsimisaraka people facts for kids

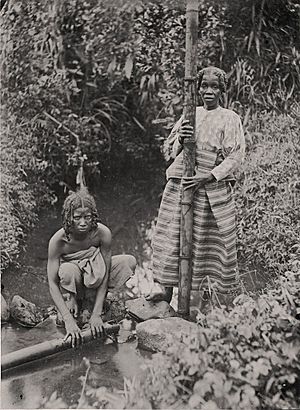

Betsimisaraka women

|

|

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| over 1,500,000 (2011) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| East coast of Madagascar | |

| Languages | |

| (Malagasy Northern Betsimisaraka) | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Tsimihety, Bantu peoples, Melanesians |

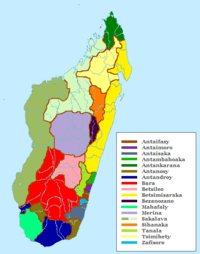

The Betsimisaraka are a large group of people living in Madagascar. Their name means "the many inseparables," showing how they came together. They are the second biggest people group in Madagascar, making up about 15% of all Malagasy people.

You can find the Betsimisaraka along the eastern coast of Madagascar. This area stretches from Mananjary in the south to Antalaha in the north. For a long time, the Betsimisaraka met many European sailors and traders. This led to a group of people called zana-malata, who have both European and Malagasy family roots.

European influences can be seen in their music, like the valse (waltz) and basesa styles, often played with an accordion. Tromba ceremonies, where people believe spirits take over, are also a very important part of Betsimisaraka culture.

In the late 1600s, different groups along the eastern coast were led by local chiefs. These chiefs usually ruled just one or two villages. Around 1710, a zana-malata leader named Ratsimilaho brought these groups together. He ruled for 50 years, creating a strong sense of shared identity and peace. However, the leaders who came after him could not keep this unity. This made the Betsimisaraka kingdom weaker and open to more influence from Europeans, especially the French.

In 1817, Radama I, the king of Imerina from the Central Highlands, took control of the Betsimisaraka kingdom. This made many Betsimisaraka people poorer. When the French colonized Madagascar (1896-1960), they tried to improve education and create jobs on French farms. Today, growing crops like vanilla, ylang-ylang, coconut, and coffee are still the main ways people earn money, along with farming for their own food and fishing. Mining also brings income to the region.

Culturally, the Betsimisaraka are split into northern and southern groups. But many traditions are shared by both. These include showing respect for ancestors, believing in spirit possession, sacrificing zebu cattle for rituals, and having a society where men are usually in charge. The groups mainly differ in their language styles and some fady (special rules or taboos). They also have different ways of doing funerals and other customs. The Betsimisaraka practice famadihana (a reburial ceremony) and believe in magic and many kinds of supernatural powers. Many taboos and stories are about lemurs and crocodiles, which are common in their land.

Contents

Who Are the Betsimisaraka?

The Betsimisaraka make up about 15% of Madagascar's population. In 2011, there were over 1,500,000 Betsimisaraka people. A special group among them, called the zana-malata, have some European family roots. This is because European pirates, sailors, and traders married local Malagasy people along the eastern coast over many years.

Like the Sakalava in the west, the Betsimisaraka are made up of many smaller groups that joined together in the early 1700s. All Malagasy people have mixed Bantu African and Asian Austronesian origins. However, the Betsimisaraka have a strong East African Bantu background, with most members being about 70% East African.

The Betsimisaraka live in a long, narrow strip of land along Madagascar's east coast. This area goes from Mananjary in the south to Antalaha in the north. It includes the island's main port city, Toamasina, and other important towns like Fénérive Est and Maroansetra. They are often divided into northern Betsimisaraka (Antavaratra) and southern Betsimisaraka (Antatsimo). The Betanimena Betsimisaraka group (once called Tsikoa) separates these two.

A Look at Betsimisaraka History

Until the early 1700s, the people who would become the Betsimisaraka lived in many small groups. Each group was led by a chief (filohany) who usually ruled only one or two villages. The northern coast had natural bays that became important port towns like Antongil, Titingue, Foulpointe, Fenerive, and Tamatave. These ports helped the northern Betsimisaraka grow in trade and power. The southern coast, however, did not have good places for ports.

Villagers near the ports traded rice, cattle, and other goods with the nearby Mascarene Islands. The eastern ports were important for trade, attracting many Europeans to this part of the island. This included British and American pirates, whose numbers grew a lot from the 1680s to the 1720s. These pirates lived along the coast from modern-day Antsiranana in the north to Nosy Boraha and Foulpointe in the east. Many of these European pirates married the daughters of local chiefs, leading to a large mixed population called zana-malata.

Around 1700, a group called the Tsikoa started to unite under strong leaders. In 1710, Ramanano, a chief from Vatomandry, was chosen as the leader of the Tsikoa ("those who are steadfast"). He began attacking northern ports. Stories say Ramanano had an armed group that burned villages, damaged tombs, and took women and children as captives. This made him known as a cruel leader.

A northern Betsimisaraka zana-malata named Ratsimilaho led a fight against these attacks. He was born around 1694 to a local chief's daughter and a British pirate named Thomas Tew. He had even traveled to England and India with his father for a short time. Despite being young, he successfully united his people. In 1712, he captured Fenerive. The Tsikoa fled across muddy red fields, which made the mud stick to their feet. This gave them a new name: Betanimena ("Many of Red Earth").

Ratsimilaho was chosen as king of all the Betsimisaraka. He was given a new name, Ramaromanompo ("Lord Served by Many"), at his main town, Foulpointe. He named his northern people Betsimisaraka to show their unity against their enemies. He then tried to make peace with the Betanimena by offering their king control of the port of Tamatave. But this peace did not last, and Ratsimilaho took back Tamatave, forcing the Betanimena king to flee south.

He also made friends with the southern Betsimisaraka and the nearby Bezanozano people. He extended his power by letting local chiefs keep their authority if they offered goods like rice, cattle, and captives. By 1730, he was one of Madagascar's most powerful kings. When he died in 1754, his fair and stable rule had brought nearly 40 years of unity to the different groups within the Betsimisaraka kingdom. He also formed an alliance with the Sakalava kingdom on the west coast by marrying Matave, the daughter of the Iboina king Andrianbaba.

Challenges After Ratsimilaho

Ratsimilaho's son, Zanahary, became king in 1755. He was a harsh leader and attacked villages under his rule. His own people killed him in 1767. Zanahary's son, Iavy, became king next. People disliked him because he continued his father's attacks and became rich by working with French traders who dealt in enslaved people.

During Iavy's rule, a European adventurer named Maurice Benyovszky set up a settlement in Betsimisaraka land. He declared himself king of Madagascar and convinced some local chiefs to stop paying tribute to Iboina. This angered the Sakalava, and in 1776, Sakalava soldiers invaded the area to punish the Betsimisaraka and try to kill Benyovszky, but they did not succeed in killing him.

Zakavolo, Iavy's son, became king after his father died in 1791. European accounts say Zakavolo demanded gifts from them and insulted them if they refused. His people removed him from power in 1803 with help from the French Governor General Magallon. Zakavolo was later killed by his former subjects.

In the years after Ratsimilaho's death, the French took control of Ile Sainte Marie and set up trading ports in Betsimisaraka land. By 1810, a French official named Sylvain Roux had strong economic control over the port city, even though Zakavolo's uncle, Tsihala, was the official ruler. A disagreement among Tsihala's male relatives over control of the city caused the Betsimisaraka's political unity to break down even more. This made it harder for them to unite against growing foreign influence. Tsihala lost power the next year to another zana-malata, Jean Rene, who worked closely with the French.

The Kingdom of Imerina in the center of the island had been growing quickly since the late 1700s. In 1817, Merina king Radama I led an army of 25,000 soldiers from Antananarivo and successfully captured Toamasina. Even though Jean Rene was not involved and did not know about the attack, Radama did not force out the Europeans and zana-malata. Instead, Radama worked with them to build relationships with the French, just as he had done with British missionaries in the Merina homeland.

The area was effectively taken over, with Merina soldiers stationed at ports and throughout Betsimisaraka territory. The Betsimisaraka did not like Merina rule. They hoped for French help but did not get it, so they started a rebellion in 1825, which failed. As Merina control grew, many local farmers moved to areas outside Merina control or found jobs with European settlers on farms, hoping for some protection.

Any remaining Betsimisaraka rulers were removed under Merina queen Ranavalona I. She ordered many nobles to undergo the deadly tangena trial, a test by ordeal. During her rule, cultural practices linked to Europeans were forbidden, including Christianity and Western music. Eventually, all Europeans were forced to leave the island for the rest of her reign.

Her son, Radama II, lifted these rules. Europeans slowly returned to Betsimisaraka land. French business owners set up farms to grow crops like vanilla, coffee, tea, and coconuts for export. More Merina settlers from the early 1800s and Europeans from the 1860s created competition for the ports. The local Betsimisaraka people were even stopped from trading to make sure the Merina and Europeans made the most money. This severe economic pressure, along with the Merina forcing them to do fanampoana (unpaid labor instead of taxes), made the local people very poor. They resisted by refusing to grow extra crops that would only benefit outside traders. Some people left their villages and hid in the forest to live outside Merina control. Some of these formed groups of bandits who robbed Merina trading parties and sometimes attacked Merina settlers, European missionaries, government posts, and churches.

French Colonial Rule and Independence

When the French took over Madagascar in 1896, the Betsimisaraka were at first happy that the Merina government was gone. But they quickly became unhappy with French control. This led to an uprising in the same year among the Betsimisaraka, especially the bandits and outlaws who had lived freely in the eastern rainforests. The movement spread to the wider Betsimisaraka population, who strongly resisted French rule in 1895. These efforts were eventually stopped.

After taking control, the French colonial government tried to fix the problems caused by the Merina kingdom's rule over the Betsimisaraka. They gave more access to basic education and jobs on farms. However, these farms were often on Betsimisaraka land that the French authorities had forced local people to give up to the colonists.

In 1947, a large uprising against French colonial rule started in Moramanga, a town near Betsimisaraka territory. During this conflict, Betsimisaraka fighters fought French and Senegalese soldiers. They tried to take back control of the port at Tamatave, which was the island's most important trading port, but they were not successful. Many Betsimisaraka fighters and civilians lost their lives.

Madagascar became an independent country in 1960. Admiral Didier Ratsiraka, a Betsimisaraka, led the country during the Second Republic (1975-1992). He was elected president and led the country again from 1995 to 2001 during the Third Republic. He was forced out of power after a disputed election in 2001 by supporters of Merina businessman Marc Ravalomanana. Didier Ratsiraka remains an important and sometimes controversial political figure in Madagascar. His nephew, Roland Ratsiraka, is also a significant political figure. He has run for president and served as mayor of Toamasina, the country's main port.

Betsimisaraka Society and Culture

Social life for the Betsimisaraka follows the farming year. Fields are prepared in October, rice is harvested in May, and the winter months from June to September are for honoring ancestors and other important rituals.

There are clear roles for men and women among the Betsimisaraka. When walking in a mixed group, women are not allowed to walk in front of men. Women traditionally carry things, light items on their heads and heavy items on their backs. If a woman is there, it is considered strange for a man to carry something. When eating, men use one spoon to take food from a shared bowl and to eat. Women must use two separate spoons, one for serving and one for eating.

Men are generally in charge of preparing rice fields, getting food, gathering firewood, and building homes and furniture. They also discuss public matters. Women's jobs include growing crops, weeding and harvesting rice, getting water, lighting the cooking fire, preparing daily meals, and weaving.

Beliefs and Traditions

Traditional religious ceremonies are led by a tangalamena official. Betsimisaraka communities widely believe in different supernatural beings. These include ghosts (angatra), mermaids (zazavavy an-drano), and small, imp-like creatures called kalamoro.

Efforts to bring Christianity to the local people began in the early 1800s but were not very successful at first. During the colonial period, more people became Christian. However, Christianity is often mixed with traditional ancestor worship. This blend of Christian and local beliefs led to the idea that the sun (or moon) was the original location of the Garden of Eden.

Many important parts of Betsimisaraka culture are similar for both northern and southern groups. Key customs include folanaka (the birth of a tenth child), sacrificing zebu cattle for ancestors, and celebrating when a new house is finished. Marriage, death, birth, the New Year, and Independence Day are also celebrated by the community.

The practice of tromba (ritual spirit possession) is common among the Betsimisaraka. Both men and women can act as mediums or watch these events.

Traditional clothing for the Betsimisaraka was made from the native raffia palm. The leaves were combed to get fibers, which were then tied together to make strands. These strands were woven into cloth. Women wore a short wrap (simbo) often with a bandeau top (akanjo), while men wore smocks. Some Betsimisaraka still wear traditional raffia clothing today.

Animals in Culture

The Betsimisaraka respect lemurs greatly. They have several legends where lemurs help important Betsimisaraka figures. One story says a lemur saved a Betsimisaraka ancestor from great danger. Another tale tells of a group of Betsimisaraka who hid in a forest from enemies. Their enemies followed them, thinking they heard their voices. When they found the source of the sound, they saw ghostly-looking lemurs. Believing the Betsimisaraka had turned into animals by magic, the enemies fled in fear.

It is believed that the spirits of Betsimisaraka ancestors live inside lemurs. Because of this, it is generally forbidden for the Betsimisaraka to kill or eat lemurs. If a lemur is trapped, it must be freed. If a lemur dies, it must be buried with the same rituals as a person.

Crocodiles are also seen with both respect and fear. At river banks where crocodiles gather, it is common for Betsimisaraka villagers to throw them offerings daily. These offerings might include zebu hindquarters (their favorite meat), whole geese, and other items. People often wear amulets for protection against crocodiles or throw them into the water where the animals gather.

It is commonly believed that witches and sorcerers are closely linked with crocodiles. They are thought to be able to order crocodiles to kill others and to walk among them without being attacked. The Betsimisaraka believe witches and sorcerers calm crocodiles by feeding them rice at night. Some are accused of walking crocodiles through Betsimisaraka villages at midnight or even being married to crocodiles, which they then force to do their bidding.

Fady (Taboos)

Among some Betsimisaraka, it is fady (forbidden) for a brother to shake hands with his sister. It is also forbidden for young men to wear shoes while their father is alive. For many Betsimisaraka, the eel is considered sacred. It is forbidden to touch, fish for, or eat eels. While many coastal Malagasy communities have a fady against eating pork, this is not common among the Betsimisaraka, who often keep pigs in their villages.

There are complex taboos and rituals for a woman's first childbirth. When she is about to give birth, she stays in a special birthing house called a komby. The leaves she eats from and the baby's waste are kept in a special container for seven days, then burned. The ash is rubbed on the mother's and baby's foreheads and cheeks and must be worn for seven days. On the fifteenth day, both are bathed in water with lime or lemon leaves. This ritual is called ranom-boahangy (bath of the leaves). The community gathers to drink rum and celebrate with wrestling matches, but the mother must stay in the komby. She can only eat saonjo greens and a specially prepared chicken. After this celebration, she can leave the komby and return to her normal life.

Among the Betsimisaraka, like some other Malagasy groups, there is a fady against saying the name of a chief after he dies, or any word that was part of his name. The dead leader was given a new name, which everyone had to use. Special substitute words were chosen to replace the forbidden words in everyday talk. Anyone who spoke the forbidden words would be severely punished, sometimes even killed.

Funeral Customs

Some Betsimisaraka, especially those near Maroantsetra, practice the famadihana reburial ceremony. However, their version is simpler than the one in the Highlands. In southern Betsimisaraka areas, coffins are placed in tombs. In the north, they are placed under outdoor shelters.

When mourning, women will undo their braided hair and stop wearing their akanjo. Men no longer wear a hat. The mourning period usually lasts two to four months, depending on how close the person was to the deceased.

Dance and Music

The ceremonial dance music style linked to tromba among the Betsimisaraka is called basesa. It is played on an accordion. Traditional basesa for tromba ceremonies uses kaiamba shakers to emphasize the beat. The songs are always sung in the local Betsimisaraka language. The dance involves keeping arms close to the body and making strong foot movements.

Modern basesa, which is popular across the island, uses a drum kit, electric guitar, bass, and keyboard or accordion. The dance style has been influenced by sega and kwassa kwassa music from Reunion Island. Basesa is also played by the Antandroy people, but among the Betsimisaraka, it is played much slower.

Another important music style in the region is valse. These are Malagasy versions of traditional European waltzes, played on the accordion. This type of music is never played during tromba ceremonies.

Betsimisaraka Language

The Betsimisaraka speak several different forms of the Malagasy language. Malagasy is part of the Malayo-Polynesian language group. It comes from the Barito languages, which are spoken in southern Borneo.

Betsimisaraka Economy

The Betsimisaraka economy is still mostly based on farming. Many people grow vanilla and rice. They also commonly grow manioc, sweet potatoes, beans, taro, peanuts, and various greens. Other important crops include sugar cane, coffee, bananas, pineapples, avocado, breadfruit, mangoes, oranges, and lychees.

Cattle are not widely raised. Instead, the Betsimisaraka often catch and sell river crabs, shrimp, and fish. They also find small hedgehogs, various local insects, or wild boar and birds in the forest. They make and sell homemade sugarcane beer (betsa) and rum (toaka).

Making spices for cooking and for distilling into perfumes is still a major economic activity. There is a perfume distillery in Fenoarivo Atsinanana. Gold, garnet, and other valuable stones are also mined and sold from the Betsimisaraka region.

Images for kids

| Percy Lavon Julian |

| Katherine Johnson |

| George Washington Carver |

| Annie Easley |