Binary pulsar facts for kids

A binary pulsar is a special type of pulsar that has a partner star orbiting it. This partner is often a white dwarf or another neutron star. In one amazing case, called PSR J0737-3039, both stars in the pair are pulsars!

Scientists love studying binary pulsars because they are like natural laboratories. They help us test general relativity, which is Einstein's theory about how gravity works, especially in very strong gravitational fields. Even if we can't see the partner star, we can measure the pulsar's regular "ticks" or pulses with incredible accuracy using radio telescopes. By carefully timing these pulses, scientists have found indirect proof of something called gravitational radiation. This confirms Einstein's theory of general relativity.

Contents

How Binary Pulsars Show Relativity in Action

Stars and planets don't orbit each other in perfect circles. Their paths are almost always shaped like an ellipse, which is like a stretched circle. This means that twice during their orbit, they get closest to each other, and twice they are furthest away. You can see this with the Earth and the Sun, and it's true for binary pulsars too.

Time Slows Down Near Strong Gravity

When the two stars in a binary pulsar system are close together, the pull of gravity is much stronger. According to Einstein's theory, time actually slows down a tiny bit in a strong gravitational field. For a pulsar, this means the time between its regular pulses (its "ticks") gets a little longer. As the pulsar moves away from its partner and the gravity gets weaker, its "clock" speeds up again, making up for the lost time. This difference in timing is called a relativistic time delay. It's the difference between what we expect to see if the pulsar moved at a steady speed and distance, and what we actually observe.

Detecting Gravitational Waves

Binary pulsars are also one of the best ways scientists can find evidence of gravitational waves. Einstein's theory predicts that two massive objects, like neutron stars, orbiting each other should create ripples in space-time called gravitational waves. These waves carry away some of the system's energy, causing the two stars to slowly spiral closer together.

Sometimes, as the stars get closer, one pulsar might pull matter from its partner. This creates a hot, glowing disk of gas around one of the stars. This process can make the system shine brightly in X-rays, which is why they are sometimes called X-ray binaries. Also, some very fast-spinning pulsars, called millisecond pulsars (MSPs), can create a strong "wind" of particles. In a binary system, this wind can affect the other star's magnetic field and change how the pulsar sends out its radio pulses.

The Discovery of the First Binary Pulsar

The very first binary pulsar, named PSR B1913+16 (also known as the "Hulse-Taylor binary pulsar"), was found in 1974. It was discovered at the Arecibo Observatory by two scientists, Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse.

A Nobel Prize-Winning Discovery

Joseph Taylor and Russell Hulse won the 1993 Nobel Prize in Physics for their amazing discovery. While Russell Hulse was observing a new pulsar, he noticed something strange: its pulse frequency kept changing. The simplest explanation was that the pulsar was orbiting another star very closely and moving very fast.

By carefully watching these pulse changes, Hulse and Taylor figured out that both stars in the system were equally heavy. This led them to believe that the partner star was also a neutron star.

Confirming Einstein's Predictions

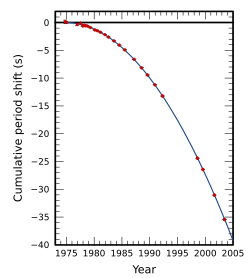

The observations of this star system's orbit were a nearly perfect match for Einstein's equations. His theory of relativity predicted that over time, a binary system would lose orbital energy by sending out gravitational radiation. This would cause the stars to spiral closer together.

Data collected by Taylor and his team showed exactly this. In 1983, they reported that the stars were reaching their closest point in orbit earlier than expected. In the first ten years after its discovery, the system's orbital period had shrunk by about 76 millionths of a second each year. This meant the pulsar was reaching its maximum separation more than a second earlier than it would have if its orbit had stayed the same. Scientists continue to observe this decrease, further supporting Einstein's theory.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Pulsar binario para niños

In Spanish: Pulsar binario para niños

| Janet Taylor Pickett |

| Synthia Saint James |

| Howardena Pindell |

| Faith Ringgold |