Bloody Sunday (1920) facts for kids

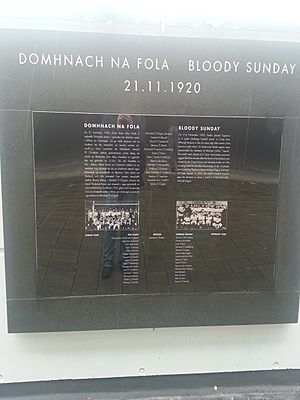

Bloody Sunday (Irish: Domhnach na Fola) was a very violent day in Dublin, Ireland, on 21 November 1920. It happened during the Irish War of Independence. More than 30 people died or were badly hurt.

The day started with a secret plan by the Irish Republican Army (IRA). This plan was led by Michael Collins. Their goal was to kill a group of British spies in Dublin, known as the "Cairo Gang". IRA members went to several places and killed or badly wounded 15 men. Most were British soldiers. Some were police officers or special police. At least two ordinary people also died. Five others were hurt. These killings made the British authorities very worried, and many British agents ran to Dublin Castle for safety.

Later that afternoon, British forces went to a Gaelic football match at Croke Park. These forces included police called "Black and Tans", special police called Auxiliaries, and British soldiers. They were sent to search everyone at the game. But without warning, the police started shooting at the people watching and playing. This killed or badly wounded 14 ordinary people and hurt at least sixty more. Two of those killed were children. Some police said they were shot at first, and the British government agreed. But everyone else said the shooting started for no reason. An army investigation later said the shooting was too much and done without thinking. This terrible event made more Irish people turn against the British.

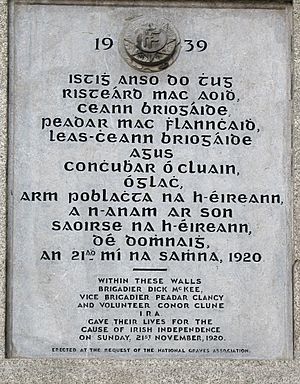

That evening, two Irish republicans, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, were killed. They had helped plan the morning's assassinations. Another person, Conor Clune, who was just caught with them, also died. British guards in Dublin Castle beat and shot them. The guards said the men were killed while trying to escape. Later, two other IRA members were found guilty and hanged in March 1921 for their part in the morning killings.

Overall, the IRA's plan hurt British spy efforts a lot. The British actions later that day made more people in Ireland and other countries support the IRA.

Contents

What Led to Bloody Sunday?

Bloody Sunday was a very important event during the Irish War of Independence. This war began after Ireland declared itself a republic and set up its own parliament, Dáil Éireann. The Irish Republican Army (IRA) fought a guerrilla war against British forces. These forces included the Royal Irish Constabulary (RIC) police and the British Army. Their job was to stop the Irish independence movement.

To fight the IRA, the British government brought more police from Britain. These new recruits were called "Black and Tans". They got this name because they wore a mix of black police uniforms and khaki army uniforms. The British also formed a special police unit called the Auxiliary Division (or "Auxiliaries"). Both groups became known for treating Irish people very harshly. In Dublin, the fighting often involved secret killings and revenge attacks from both sides.

The events of 21 November were the IRA's attempt to break the British spy network in Dublin. This plan was led by Michael Collins and Richard Mulcahy.

Collins's Secret Plan

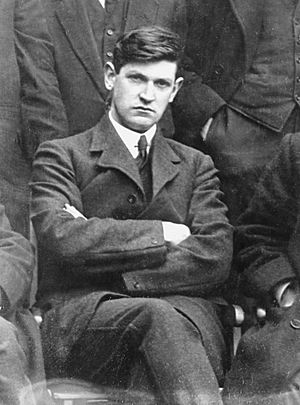

Michael Collins was the IRA's main spy chief and also a finance minister for the Irish Republic. Since 1919, he had a secret group of IRA members in Dublin called "The Squad". They were also known as "The Twelve Apostles". Their job was to kill important RIC officers and British agents, especially those they thought were spies.

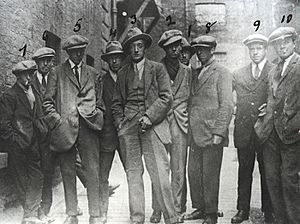

By late 1920, British spies had a large network in Dublin. This included eighteen British agents known as the "Cairo Gang". They got this name because they often met at the Cairo Café. Many of them had also worked in British military intelligence in Egypt and Palestine during World War I. Mulcahy, the IRA's Chief of Staff, called them "a very dangerous and clever spy group".

In early November 1920, some important IRA members in Dublin almost got caught. On 10 November, Mulcahy barely escaped a British raid. But the British found documents with names and addresses of 200 IRA members. Soon after, Collins ordered the killing of British agents in the city. He believed that if they didn't act, the IRA in Dublin would be in great danger. The IRA also thought the British were trying to kill their leaders.

Dick McKee was in charge of planning the operation. The addresses of the British agents came from many places. These included maids and servants who supported the IRA, careless talk from some British agents, and an IRA spy inside the RIC police. Collins first wanted to kill more than 50 suspected British spies. But the list was cut to 35 by Cathal Brugha, the Irish Minister for Defence. He felt there wasn't enough proof against some people. The number was then lowered again to 20.

On the night of 20 November, the IRA teams got their final orders. They were told about their targets: 20 agents at eight different places in Dublin. Two of the leaders at this meeting, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, were arrested a few hours later. Collins himself also barely escaped capture in another raid.

Bloody Sunday Events

Morning: IRA Attacks

Quick facts for kids Bloody Sunday shootings |

|

|---|---|

A photo thought to be of the Cairo Gang.

|

|

| Location | central Dublin |

| Date | 21 November 1920 Early morning (GMT) |

|

Attack type

|

Assassinations |

| Weapons | revolvers, semi-automatic pistols |

| Deaths | 15:

|

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

5 |

| Perpetrator | Irish Republican Army |

Early on the morning of 21 November, the IRA teams began their attacks. Most of the killings happened in a small, middle-class area of south Dublin. Two shootings also took place at the Gresham Hotel on Sackville Street (now O'Connell Street). At 28 Upper Pembroke Street, six British Army officers were shot. Three spy officers died right away. A fourth, Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Montgomery, died later from his wounds. The others survived. Another successful attack happened at 38 Upper Mount Street, where two more spy officers were killed. A British Army messenger rode into the attack on Upper Mount Street. The IRA held him at gunpoint. As they left, the IRA shot at a British major who saw them from a nearby house.

At 22 Lower Mount Street, one spy officer was killed, but another got away. A third officer, named "Peel", stopped the attackers from getting into his room. Then, members of the Auxiliary Division, who were passing by, surrounded the building. The IRA team had to shoot their way out. One IRA volunteer, Frank Teeling, was shot and caught as the team ran away. Meanwhile, two Auxiliaries had been sent to get more help from a nearby army base. An IRA team caught them on Mount Street Bridge. They were taken to a house, questioned, and shot dead. They were the first Auxiliaries killed while on duty.

At 117 Morehampton Road, the IRA killed a sixth spy officer. But they also shot his landlord, who was an ordinary person, probably by mistake. At the Gresham Hotel, they killed two more men who seemed to be ordinary people. Both were former British officers from World War I. The IRA team had told a hotel worker to take them to certain rooms. In one room, the person killed (MacCormack) was likely not the intended target. It's not clear if the other person killed (Wilde) was a spy. One IRA team member, James Cahill, said Wilde told them he was a spy officer when asked his name. He might have thought they were police.

One of the IRA volunteers in these attacks, Seán Lemass, later became a famous Irish politician. On Bloody Sunday morning, he took part in killing a British court-martial officer at 119 Lower Baggot Street. Another court-martial officer was killed on the same street. At 28 Earlsfort Terrace, an RIC police sergeant named Fitzgerald was killed. But the target was likely a British lieutenant-colonel named Fitzpatrick.

There has been some confusion about who the IRA killed that morning. At the time, the British government said the men killed were just regular British officers or innocent people. The IRA believed most of their targets were British spies. Later studies have shown that most of the British officers killed were indeed involved in spy work. However, some were not, and some innocent people were killed by mistake.

In total, 14 men died right away, and one more died later from his wounds. Five others were hurt but lived. Only one IRA member, Frank Teeling, was caught, but he escaped from prison soon after. Another IRA volunteer was slightly hurt. An IRA volunteer and future politician, Todd Andrews, later said that many IRA attacks failed. The targets weren't home, or the attackers made mistakes.

People killed by the IRA in the morning:

- Lieutenant Peter Ames (British Army Spy Officer)

- Lieutenant Henry Angliss (British Army Spy Officer)

- Lieutenant Geoffrey Baggallay (British Army Court-Martial Officer)

- Lieutenant George Bennett (British Army Spy Officer)

- Major Charles Dowling (British Army Spy Officer)

- Sergeant John Fitzgerald (RIC police officer)

- Auxiliary Frank Garniss (Special RIC police)

- Lieutenant Donald MacLean (British Army Spy Officer)

- Patrick MacCormack (ordinary person, former British Army captain)

- Lieutenant-Colonel Hugh Montgomery (British Army Staff Officer) – died later

- Auxiliary Cecil Morris (Special RIC police)

- Captain William Newberry (British Army Court-Martial Officer)

- Captain Leonard Price (British Army Spy Officer)

- Thomas Smith (ordinary person, MacLean's landlord)

- Leonard Wilde (ordinary person and possible spy)

Afternoon: Croke Park Shooting

| Croke Park massacre | |

|---|---|

British soldiers and families of victims outside a hospital after the Croke Park shooting.

|

|

| Location | Croke Park, Dublin |

| Date | 21 November 1920 15:25 (GMT) |

|

Attack type

|

Mass shooting |

| Weapons | Rifles, revolvers and an armoured car |

| Deaths | 14 civilians |

|

Non-fatal injuries

|

80 civilians |

| Perpetrator | Royal Irish Constabulary Auxiliary Division |

The Dublin Gaelic football team was set to play the Tipperary team later that day. The game was at Croke Park, the main football ground for the Gaelic Athletic Association. Money from ticket sales would go to help families of Irish prisoners. Even though there was tension in Dublin after the morning's killings, people still went about their lives. At least 5,000 people went to Croke Park. The match started 30 minutes late, at 3:15 p.m.

Meanwhile, without the crowd knowing, British forces were getting ready to raid the match. A group of soldiers in trucks and three armoured cars came from the north. They stopped along Clonliffe Road. Another group of RIC police came from the southwest. This group had 12 trucks of Black and Tans in front and six trucks of Auxiliaries behind. Some plain-clothes Auxiliaries also rode with the Black and Tans. Their orders were to surround Croke Park, guard the exits, and search every man. The British authorities later said they planned to announce by megaphone that all men leaving would be searched. They also said anyone trying to leave another way would be shot. However, for some reason, police started shooting as soon as they reached the southwest gate at 3:25 p.m.

Some police later said they were shot at first when they arrived outside Croke Park. They claimed IRA guards shot at them. But other police at the front of the group did not say this, and there is no strong proof for it. Everyone who saw it agreed that the RIC police started shooting without being provoked as they ran into the grounds. Two Dublin police officers on duty near the gate did not report the RIC being shot at. Another Dublin police officer said an RIC group also came to the main gate and started shooting into the air. The police in the first trucks seemed to jump out, run to the gate, force their way through, and start shooting quickly with rifles and revolvers.

The police kept shooting for about 90 seconds. Their commander, Major Mills, later admitted his men were "excited and out of hand". Some police shot into the running crowd from the field. Others, outside the grounds, shot from the Canal Bridge at people climbing over a wall to escape. On the other side of the Park, soldiers on Clonliffe Road were surprised by the shooting. Then they saw panicked people running from the grounds. As people streamed out, an armoured car fired its machine guns over the crowd, trying to stop them.

By the time Major Mills got his men under control, the police had fired 114 rifle rounds. The armoured car outside the Park fired 50 rounds. Seven people had been shot and died. Five more were shot and so badly wounded that they died later. Another two people died in the crowd crush. The dead included Jane Boyle, the only woman killed. She had gone to the match with her fiancé and was due to be married five days later. Two boys, aged 10 and 11, were shot dead. Two football players, Michael Hogan and Jim Egan, were shot. Egan lived, but Hogan was killed. He was the only player to die. Dozens of others were wounded or injured. The police group had no injuries.

After the shooting stopped, the security forces searched the men who remained before letting them go. The military group found one revolver. A local homeowner said a fleeing spectator had thrown it in his garden. The British authorities said 30-40 discarded revolvers were found in the grounds. However, Major Mills said no weapons were found on the spectators or in the grounds.

The police's actions were not officially allowed. The British authorities in Dublin Castle were horrified.

The Times newspaper, which usually supported the British, made fun of Dublin Castle's story. A British Labour Party group visiting Ireland also did. British Brigadier Frank Percy Crozier, who led the Auxiliary Division, later quit. He believed the government was accepting the Auxiliaries' unfair actions in Croke Park. One of his officers told him that "Black and Tans fired into the crowd without any reason at all". Major Mills said: "I did not see any need for any firing at all".

People killed at Croke Park:

- Jane Boyle (26), Dublin

- James Burke (44), Dublin

- Daniel Carroll (31), Tipperary (died 23 November)

- Michael Feery (40), Dublin

- Michael 'Mick' Hogan (24), Tipperary

- Tom Hogan (19), Limerick (died 26 November)

- James Matthews (38), Dublin

- Patrick O'Dowd (57), Dublin

- Jerome O'Leary (10), Dublin

- William Robinson (11), Dublin

- Tom Ryan (27), Wexford

- John William Scott (14), Dublin

- James Teehan (26), Tipperary

- Joe Traynor (21), Dublin

Evening: Dublin Castle Killings

Later that night, two high-ranking IRA officers, Dick McKee and Peadar Clancy, were killed. Another man, Conor Clune, also died. They were being held and questioned in Dublin Castle. McKee and Clancy had helped plan the morning's killings of British agents. They had been caught in a raid just hours before those attacks. Clune was the nephew of Archbishop Patrick Clune from Australia. He had joined the Irish Volunteers when it started, but it's not clear if he was actively involved. He was arrested in another raid on a hotel that IRA members had just left.

Their captors said that there was no room in the cells. So, the prisoners were put in a guardroom with weapons. The guards said the men were killed while trying to escape. They claimed the men threw grenades that didn't explode. Then, they supposedly shot at the guards with a rifle but missed. Auxiliaries shot them. Doctors found broken bones and bruises on their bodies, showing they had been beaten for a long time. They also had bullet wounds to the head and body. Their faces were covered in cuts and bruises. McKee had what looked like a bayonet wound in his side. An IRA leader, Michael Lynch, said McKee was badly beaten before being shot.

However, Clune's boss, Edward MacLysaght, saw the bodies at the hospital. He said the claim that their faces were "unrecognisable and horrible" was not true. He remembered their "pale dead faces" as not disfigured. An army doctor who checked the bodies found some skin discoloration. But he said this could have happened because of how the bodies were lying. He found many bullet wounds but no other injuries like bayonet wounds. The head of British Intelligence, Brigadier General Ormonde Winter, did his own investigation. He interviewed the guards and checked the scene. He said he was happy with their story.

Aftermath

The IRA's attacks on British agents and the British shooting of civilians together hurt British power. They also made more people support the IRA. The killings at the football match, including a woman, several children, and a player, made international news. This damaged Britain's reputation and made the Irish public even more against the British. Some newspapers at the time compared the Croke Park shootings to the Amritsar massacre in India in 1919.

When Joseph Devlin, an Irish Member of Parliament (MP), tried to talk about the Croke Park killings in the British Parliament, other MPs shouted him down and attacked him. The meeting had to be stopped. There was no public investigation into the Croke Park shooting. Instead, two British military investigations were held in secret. More than 30 people gave evidence, most of them anonymous Black and Tans, Auxiliaries, and British soldiers. One investigation concluded that unknown civilians probably shot first. But it also said: "the fire of the RIC was carried out without orders and was more than needed". Major General Boyd, the British officer in charge of Dublin, added that the shooting at the crowd "was done without thinking, and could not be justified". The British Government kept the results of these investigations secret. They only became known in 2000.

The IRA killings caused panic among British military leaders. Many British agents ran to Dublin Castle for safety. In Britain, the deaths of the British Army officers got more attention at first. The bodies of nine of the killed officers were taken in a procession through London for their funerals. In Dublin, the fate of the British agents was seen as a victory for IRA intelligence. But British Prime Minister David Lloyd George said his men "got what they deserved". Winston Churchill added that the agents were "careless fellows... who ought to have taken precautions".

One IRA member was caught during the morning killings, and several others were arrested in the following days. Frank Teeling (who was caught) was put on trial for killing Lieutenant Angliss. Teeling and two others were found guilty and sentenced to death. Teeling escaped from prison, and the other two were later pardoned. Thomas Whelan was arrested for killing Lieutenant Baggallay and was executed on 14 March 1921. Patrick Moran was sentenced to death for the Gresham Hotel killings and also executed on 14 March.

The Gaelic Athletic Association (GAA) named one of the stands in Croke Park the Hogan Stand. This was in memory of Michael Hogan, the football player killed in the incident.

IRA killings continued in Dublin for the rest of the war. The Dublin IRA also carried out more large-scale attacks in the city. By spring 1921, the British had rebuilt their spy network in Dublin. The IRA was planning another attempt to kill British agents that summer. However, many of these plans were stopped because a truce ended the war in July 1921.

Trial for Lower Mount Street Killings

A trial for the Lower Mount Street killings happened at City Hall in Dublin on 25 January 1921. Four men were accused: William Conway, Daniel Healy, Edward Potter, and Frank Teeling. Daniel Healy was given a separate trial. The trial for the other three men went ahead. They were accused of killing Lieutenant H. Angliss, also known as Mr. McMahon, at 22 Lower Mount Street. People all over Ireland followed the trial, and many Irish and international newspapers reported on it.

A witness known as "Mr. C" gave evidence on 28 January. He was identified as Lieutenant John Joseph Connolly, the man sleeping in the same bed who escaped by jumping out the window. Another witness, "Mr. B", was later identified as Lt Charles R. Peel.

The Irish Independent newspaper reported that a witness said he didn't see Teeling in the house. He saw him being carried out from the yard. Another witness said she was taken to a barracks where she identified Potter from a line-up of eight prisoners.

Frank Teeling later escaped from Kilmainham prison in a daring plan organized by Collins.

The Irish Times reported that on 6 March 1921, the death sentences for Conway and Potter were changed to prison time. Daniel Healy was eventually found not guilty.

See also

- List of massacres in Ireland

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |