Bluffton, Georgia facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Bluffton, Georgia

|

|

|---|---|

Post office

|

|

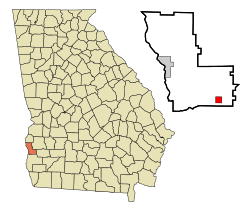

Location in Clay County and the state of Georgia

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Georgia |

| County | Clay |

| Government | |

| • Type | City commission government |

| Area | |

| • Total | 1.61 sq mi (4.16 km2) |

| • Land | 1.61 sq mi (4.16 km2) |

| • Water | 0.00 sq mi (0.00 km2) |

| Elevation | 318 ft (97 m) |

| Population

(2020)

|

|

| • Total | 113 |

| • Density | 70.27/sq mi (27.13/km2) |

| Time zone | UTC-5 (Eastern (EST)) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC-4 (EDT) |

| ZIP codes |

31724, 39824

|

| Area code(s) | 229 |

| FIPS code | 13-08956 |

| GNIS feature ID | 0311579 |

Bluffton is a small town in Clay County, Georgia, United States. In 2020, about 113 people lived there. It's known for its interesting history and its connection to the early days of Georgia.

Contents

History

The Georgian Revolt: A Fight for Local Control

The Georgia Colony was started in 1732 by James Oglethorpe. He wanted Georgia to be a special place. It was meant to be a safe spot for people who had committed small crimes. Oglethorpe also worked hard to have good relationships with the local Native American tribes. For a while, Georgia was one of the few colonies where slavery was against the law.

However, the leaders of the colony, called The Georgia Trustees, slowly changed Oglethorpe's ideas. When slavery became legal in 1750, many of Oglethorpe's supporters moved west. They went to land controlled by the Creek and Cherokee tribes, which is now known as Clay County.

Early Ideas for Self-Rule

In 1779, two leaders from Bluffton, Jonathon Jones and Sam Whitfields, wrote a document called the Articles of Constitutional Sovereignty. They wanted the state of Georgia to include rules in its constitution that would give small towns more say in their own government. They believed towns should have the right to govern themselves. They sent their ideas to Georgia's state government.

Working with Native Allies

After the state government said no to their first plan, the leaders in Clay County talked to the Coweta, a group within the Creek Confederacy. The Coweta and Cherokee tribes had lost a lot of land in 1773 because of the Treaty of Augusta. This made them feel a strong connection to the small towns in western Georgia, like Bluffton, who also felt ignored by the state.

The Coweta sent representatives to meet with the "Constitutional Committee of Georgia," which was made up of leaders from several towns in Clay County. Together, they wrote two important documents:

- A letter of complaints to the Governor of Georgia.

- A plan for how the Anglo-Creek Confederacy (the alliance between the towns and tribes) would work. This plan was first called The Treatise of Bluffton.

They sent their complaints to Governor Edward Telfair, who had been fair to the Creek people in the past. They also asked for their ideas to be included in the state's new constitution in 1798. But in 1793, Telfair was replaced by George Mathews, who supported plantation owners and was not as friendly to the Creek. The state government, now controlled by a group called the Federalists, officially rejected Bluffton's ideas in 1794.

The Clay County Plan for Self-Government

Because their ideas were rejected, the leaders of Clay County and the Coweta met again in Bluffton. This meeting, called the 2nd Anglo-Creek Convention, included representatives from six towns and eight Creek tribes. They created a plan called the Document of Administration for Clay County. It had seven main points:

- Towns and tribes would form a loose alliance.

- Each town would pay a small tax to create a well-organized army of citizens and Creek warriors.

- The Creek tribes would remain mostly independent but would be seen as citizens of Clay County.

- They planned to work together economically to become more independent.

- They hoped to stop needing a military within ten years, not expecting a fight with the state or federal government.

- They would send representatives to the state government.

- They would encourage other towns to support their ideas for a new government structure.

The leaders believed their plan could be a model for how local communities could work within the United States. They thought towns should have some political freedom and their own ideas, even with strong state and federal governments.

The Yazoo Act and Growing Tensions

In 1795, a big event happened in western Georgia. Governor George Mathews signed the Yazoo Land Act. This act allowed the sale of nearly 35 million acres of Creek and Cherokee land for a very low price. Many people in Georgia, and some politicians, were very angry about this deal.

The people of Clay County saw this as the government taking too much power and threatening their freedom. So, the alliance of Native tribes and Georgian towns met again in Bluffton in 1795. This time, there was a disagreement among the leaders. Those closer to the eastern border, where settlers were moving in, wanted to declare independence and write their own constitution. The original leaders from Bluffton worried this would attract too much negative attention from the state government.

After two weeks of talks, they reached a compromise. They added three changes to their governing document:

- They named their alliance the District of Clay County (DCC). This showed they still wanted to be part of Georgia.

- They clearly described how the DCC would be governed.

- They set the boundaries of the DCC and explained how new towns could join.

Expanding the District of Clay County

With their new plan, the leaders of Bluffton realized their district now had official borders. They had to figure out how to govern their land. Towns on the eastern edge of the DCC started asking nearby settlements to join, and many agreed.

However, when the town of Morgan refused to join, the DCC faced its first possible military problem. An emergency meeting was called in Bluffton on May 5, 1795, to stop any fighting. But before the council could act, a small group from the town of Edison, along with some Native warriors, attacked Morgan. Most people in Morgan welcomed them, but a few officials who didn't want to join the DCC escaped to Savannah to tell the state government about the uprising.

The DCC force then marched towards Leary, a town outside their borders. They met little resistance. Meanwhile, the Bluffton council was upset about the Edison group's actions. They quickly sent a part of their militia, led by Creek General Onetiwa, to stop them.

The two small armies met near Leary on May 12. General Onetiwa met with James Walters, the mayor of Edison and leader of the Edison force. Onetiwa wanted Walters to retreat to Bluffton, but Walters refused. So, Onetiwa camped outside Leary to watch Walters's force. This led to a two-week standoff between the two groups, which together had about 300 men.

Changes in Georgia and the DCC

During the standoff at Leary, the DCC held its first elections. Many representatives who wanted more expansion and independence were elected from the eastern border towns. When the new leaders met in September 1795, they tried to pass laws for more expansion. But Whitfield and Jones, who were still in charge, rejected these bills.

In 1796, the political situation in Georgia changed. Many new leaders were elected, including Governor Jared Erwin and James Jackson, who strongly opposed the Yazoo Act. In February, Jackson successfully passed the Rescinding Act, which canceled the Yazoo Act.

However, Jackson also wanted to remove Native Americans from the Yazoo territory. With the Bluffton government in turmoil, Thomas Bailey, a new leader, proposed a plan to capture the city of Albany. Even though his idea was laughed at, Bailey secretly told the military forces on the eastern border, led by Generals Menewa and Oliver Herald, that the plan had passed. He ordered them to march on Albany immediately.

The DCC force, made up of about 300 Creek and Clay soldiers, easily defeated the small Georgian militia in Albany. Herald and his men wanted to keep going and conquer more towns, but one of Menewa's officers convinced him to wait for more orders.

Declaring Independence

The Bluffton Council was very angry about Bailey's actions, but Bailey and his supporters celebrated the victory at Albany. The nearby town of Blakley then asked to join the DCC and was accepted in June 1796. In July, King George III of Britain even sent a letter to the Bluffton council, offering money if the DCC declared independence. Many of the original leaders felt this would go against their first goals.

The council debated for two months. Whitfield and Jones worked to make sure their declaration was based on the original Articles of Constitutional Sovereignty. It even included a part saying they would rejoin Georgia if their requests were met. The committee also created two new rules for how the government would work, which were sent to the towns for approval. The DCC officially declared its independence on December 6, 1796.

The Battles for Albany and Leary

The DCC began building up its army, with each part led by both a Creek and a town general. The military leaders considered attacking Sasser. But on January 10, 1797, the DCC's declaration reached the Governor of Georgia. The next day, about 500 Georgian soldiers marched on Albany.

The DCC force, led by General Onetiwa, met them at the Blenheim bridge. A small group of 250 Creek warriors shot arrows from a distance, while riflemen stopped the Georgians from crossing the river. In just 30 minutes, the Georgian lines broke. They retreated, having lost 75 men, while the Creek lost only one.

Despite this victory, the DCC was not ready for a full war with the state. They were waiting for British help that hadn't arrived. Also, the leaders in Bluffton were divided, with some wanting full war and others not. Unable to organize their army, Bailey sent a message to Menewa's forces to reinforce Onetiwa at Albany.

On January 18, a tired force of 600 men heard that 1,000 Georgian militia were marching on Albany again. Onetiwa organized his archers, and Menewa prepared his men. Menewa was told to retreat from the city if a battle started and meet the Georgians outside, while Onetiwa held the city. Even with war coming, Jones and Whitfield still wanted to keep public support for the DCC.

Georgia's army, led by General John R. Higgins, was ready for Onetiwa's defense this time. He spread out his forces and attacked Menewa's small groups protecting each entrance. But before Higgins's forces could take the city, the rest of Menewa's army attacked the Georgians from behind, drawing them away from the city. As the Georgians chased Menewa towards Leary, Onetiwa's archers escaped the city and returned to Bluffton. When Higgins returned, the city was quiet except for the townspeople.

Even though it seemed like a defeat, the DCC's smaller force had caused another 100 Georgian casualties while only losing 20. Both sides knew they were in for a long fight.

Over the next few months, the DCC built up its military at Leary, getting ready for a Georgian attack. Britain sent them money and weapons. In May, the attack came: 5,000 Georgian men against 3,000 for the DCC. The first battle lasted six days around Leary. The fighting became like guerrilla warfare, with small, quick attacks. Both sides lost about 500 men without gaining much land.

For the next five years, fighting continued on the DCC's eastern border. With help from Britain, the DCC managed to hold off the Georgian forces without too much trouble for the DCC itself.

In 1798, Jackson became Governor again. He pushed for Georgia to sell the land, including the DCC's territory, to the federal government. In 1802, he succeeded, selling the land for $1.25 million.

The End of the District of Clay County

Within a month of the land sale, President Jefferson sent 10,000 U.S. soldiers. When they arrived in Clay County, they found the DCC's army tired and disorganized, not ready for such a large, well-trained force. Within one day, the DCC's army retreated from Leary to Cuthbert and Bluffton.

By the summer of 1802, the DCC was forced to give up Bluffton. Jones, Bailey, and Creek leader Talof Harjo met with U.S. General Jamison T. Williams at Fort Gaines. With very little power to negotiate, Bluffton's leaders and the Creek agreed to give up all their land in the Clay County area. About 10,000 people who supported the DCC were forced to move west. For the next 50 years, Bluffton and the towns around it were mostly empty.

This marked the end of a unique and little-known experiment in U.S. history.

Modern Bluffton

Bluffton has had a post office since 1875. The town officially became a town in 1887. Today, the White Oak Pastures organic farm is located there.

Geography

Bluffton is located at 31°31′20″N 84°52′1″W / 31.52222°N 84.86694°W.

U.S. Route 27 runs north and south just east of the town. It's a four-lane highway that goes north about 19 miles (31 km) to Cuthbert and south about 13 miles (21 km) to Blakely.

The United States Census Bureau says that Bluffton covers a total area of 1.6 square miles (4.1 km2), and all of it is land.

Demographics

| Historical population | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Census | Pop. | %± | |

| 1880 | 76 | — | |

| 1890 | 298 | 292.1% | |

| 1900 | 312 | 4.7% | |

| 1910 | 325 | 4.2% | |

| 1920 | 301 | −7.4% | |

| 1930 | 292 | −3.0% | |

| 1940 | 246 | −15.8% | |

| 1950 | 244 | −0.8% | |

| 1960 | 176 | −27.9% | |

| 1970 | 105 | −40.3% | |

| 1980 | 132 | 25.7% | |

| 1990 | 138 | 4.5% | |

| 2000 | 118 | −14.5% | |

| 2010 | 103 | −12.7% | |

| 2020 | 113 | 9.7% | |

| U.S. Decennial Census 1850-1870 1870-1880 1890-1910 1920-1930 1940 1950 1960 1970 1980 1990 2000 2010 2020 |

|||

How Many People Live Here? (2020 Census)

In 2020, Bluffton had 113 people. Here's a quick look at the population:

| Race / Ethnicity | Pop 2020 | % 2020 |

|---|---|---|

| White (not Hispanic) | 92 | 81.42% |

| Black or African American (not Hispanic) | 16 | 14.16% |

| Mixed Race/Multi-Racial (not Hispanic) | 2 | 1.77% |

| Hispanic or Latino (any race) | 3 | 2.65% |

| Total | 113 | 100.00% |

Note: The U.S. Census counts Hispanic/Latino as an ethnic group. People of Hispanic/Latino background can be of any race.

A Look Back: 2010 Census

In 2010, there were 103 people living in Bluffton.

- About 82.5% were White.

- About 14.6% were African American.

- About 2.9% were from two or more races.

- About 1.9% were Hispanic or Latino.

In 2000, there were 118 people, with 49 households and 34 families. The average household had about 2.41 people. The median age was 49 years old.

See also

In Spanish: Bluffton (Georgia) para niños

In Spanish: Bluffton (Georgia) para niños