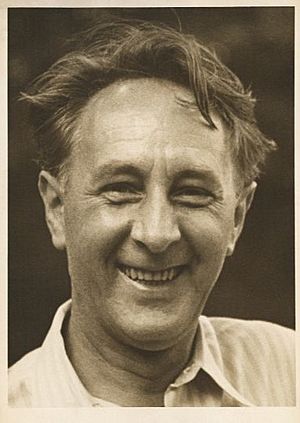

Bohuslav Martinů facts for kids

Bohuslav Martinů (born December 8, 1890 – died August 28, 1959) was a famous Czech composer. He wrote many different kinds of music. He created 6 symphonies, 15 operas, and 14 ballets. He also wrote lots of music for orchestras, small groups of instruments (called chamber music), and singers.

Bohuslav started as a violinist in the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. He even studied for a short time with the Czech composer Josef Suk. In 1923, Martinů left Czechoslovakia and moved to Paris. There, he started to move away from the older, Romantic style of music he had learned.

In the 1920s, he tried out new French music styles. You can hear this in his orchestral pieces like Half-time and La Bagarre. He also used jazz music in his works, for example, in his ballet Kitchen Revue.

By the early 1930s, he found his main style: neoclassicism. This style used ideas from older music but with a modern twist. He wrote a lot of music very quickly during this time. His Concerto Grosso and the Double Concerto for Two String Orchestras, Piano and Timpani are well-known from this period. His operas Juliette and The Greek Passion are thought to be his best.

Martinů was good at adding Czech folk music into his compositions. He kept using traditional Bohemian and Moravian folk melodies throughout his life. An example is his cantata The Opening of the Springs.

His symphonic career really took off when he moved to the United States in 1941. He was escaping the German invasion of France. All six of his symphonies were played by major US orchestras. Martinů returned to Europe for two years starting in 1953. Then he went back to New York. He finally returned to Europe in May 1956 and passed away in Switzerland in August 1959.

Contents

His Life Story

Early Years (1890–1923): Polička and Prague

Bohuslav Martinů was born in a very unusual place. He was born in the tower of the St. Jakub Church in Polička, a town in Bohemia. His father, Ferdinand, was a shoemaker. He also worked as the church caretaker and fire watchman. Because of this, his family lived in the tower apartment.

As a young boy, Bohuslav was often sick. His father or older sister often had to carry him up the 193 steps to the tower. At school, he was very shy. He didn't join in plays or school events. But he was an excellent violinist. He became well-known for his playing. He gave his first public concert in his hometown in 1905.

The people of Polička raised money to help him go to school. In 1906, he left his hometown to study at the Prague Conservatory.

At the Conservatory, he wasn't a good student. He didn't like the strict teaching style. He also didn't like the many hours of violin practice. He preferred to explore Prague on his own. He went to concerts and read many books. His roommate, Stanislav Novák, was a brilliant violinist and a great student.

They often went to concerts together. Martinů loved to analyze new music, especially French impressionist works. He could remember much of the music. When they returned to their room, he could write down large parts of the score almost perfectly. Novák was amazed by Martinů's incredible musical memory and analysis skills.

They became lifelong friends. Martinů was eventually removed from the violin program. He was moved to the organ department, which taught composition. But in 1910, he was dismissed for "not paying attention."

Martinů then spent several years back home in Polička. He tried to make a name for himself in music. He had already written several pieces. These included Elegie for violin and piano, and the symphonic poems Angel of Death and Death of Tintagiles. He sent his work to Josef Suk, a leading Czech composer. Suk encouraged him to get formal composition training. But this would not happen for years.

During World War I, Martinů passed a teaching exam. He taught music in Polička. He also kept composing and studying on his own. At this time, he studied old choral hymns. These hymns would later influence his music style.

When World War I ended, Czechoslovakia became an independent country. Martinů composed a special song called Czech Rhapsody to celebrate. It was first performed in 1919 and was very popular. He traveled around Europe as a violinist with the National Theatre Orchestra. In 1920, he joined the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra. The conductor, Václav Talich, was the first important conductor to support Martinů's music. Martinů also began formal composition lessons with Suk. In these last years in Prague, he finished his first string quartet and two ballets: Who is the Most Powerful in the World? and Istar.

Life in Paris (1923–1940)

In 1923, Martinů finally moved to Paris. He had a small scholarship from the Czechoslovak Ministry of Education. He wanted to study with Albert Roussel, whose unique style he admired. Roussel taught Martinů until his death in 1937. He helped Martinů organize his compositions. He didn't force him to write in a specific style.

In his first years in Paris, Martinů tried out many new trends. These included jazz, neoclassicism, and surrealism. He especially liked the composer Stravinsky. Stravinsky's music had new, sharp rhythms that showed the modern world. Ballets were Martinů's favorite way to experiment. Some of his ballets from this time include The Revolt (1925), The Butterfly That Stamped (1926), Le raid merveilleux (1927), La revue de cuisine (1927), and Les larmes du couteau (1928).

Martinů made friends in the Czech artistic community in Paris. He always stayed close to his home country. He often went back during the summer. He continued to find musical ideas from his Bohemian and Moravian roots. His most famous work from this time is the ballet Špalíček (1932–33). It uses Czech folk tunes and nursery rhymes.

A key person for new symphonic music in Paris was Serge Koussevitzky. He conducted concerts from 1921 to 1929. He became the conductor of the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1924. But he still returned to Paris each summer for his concerts. In 1927, Martinů met him by chance at a café. He introduced himself and gave Koussevitzky the score for La bagarre. This piece was inspired by Charles Lindbergh's recent airplane landing. Koussevitzky was impressed. He scheduled its first performance with the Boston Symphony in November 1927.

In 1926, Martinů met Charlotte Quennehen. She was a French seamstress. She moved into his small apartment and helped support him. She became very important in his life. She managed their home and business matters, which he found difficult. They married in 1931.

By 1930, Martinů had settled on a neoclassical style. In 1932, he won a prize for his String Sextet with Orchestra. Koussevitzky performed this with the Boston Symphony Orchestra in 1932. Martinů finished his opera Julietta in 1936. It was based on a play he had seen in 1927. It was first performed in Prague in 1938.

In 1937, Martinů met a young Czech woman named Vítězslava Kaprálová. She was a talented musician. She came to Paris to study conducting and composition. Martinů composed one of his greatest works, the Double Concerto for two string orchestras, piano and timpani, around this time. He finished it just before the Munich Agreement in September 1938.

After the Munich Agreement, the Czech government formed a government in exile in France and England. Martinů tried to join the Czech resistance force but was too old. However, in 1939, he wrote a tribute to this force, the Field Mass. It was broadcast from England and heard in occupied Czechoslovakia. Because of this, Martinů was blacklisted by the Nazis. He was sentenced in absentia (meaning, without being there).

In 1940, as the German army neared Paris, the Martinůs fled. They were helped by Charles Munch. They stayed in Aix-en-Provence for six months. They tried to find a way to leave Vichy France. The Czech artistic community helped him. Despite the hard times, he found inspiration in Aix. He composed several works, like the Sinfonietta giocosa. Finally, on January 8, 1941, they left France. They traveled through Madrid and Portugal. They reached the United States in 1941. His friend, Miloš Šafránek, and his Swiss supporter, Paul Sacher, helped them greatly.

Years in the US (1941–1953)

Life in the United States was hard for Martinů at first. Many artists who moved there faced similar problems. They didn't know English, had little money, and found few chances to use their talents. When they arrived in New York, the Martinůs rented a small apartment. Friends like pianist Rudolf Firkušný helped them.

Martinů found it hard to compose in noisy Manhattan. So, they moved to a quiet apartment in Jamaica Estates, Queens. This neighborhood was good for him. He would take long walks at night and work out music in his head. Sometimes, he would get so lost in thought that he'd get lost himself! He would then call a friend to pick him up. After this, he started composing actively.

When he contacted Serge Koussevitzky, the conductor told him his Concerto Grosso would be performed in Boston. One of the first pieces Martinů wrote in New York was the Concerto da Camera for violin and small orchestra. He had been asked to write this before the war. The next year, they moved back to Manhattan. They lived there for the rest of their time in America.

As World War II ended, Martinů faced personal challenges. His wife, Charlotte, really wanted to go back to France. He didn't. So, when he accepted an offer to teach music in Massachusetts in 1946, she went to France alone.

In Massachusetts, Martinů stayed in a castle with students. One night, he fell from a terrace that had no railing. He landed on concrete and was badly hurt. He had a fractured skull and a concussion. He was in and out of a coma but survived. After weeks, he went to recover with friends. It took a few years for him to fully recover and return to composing as before.

Martinů was unsure where he would live. He thought about returning to Czechoslovakia to teach. But he had a powerful enemy there, a communist politician. Any plans to return were stopped by the communist takeover in 1948. With the communists in power, music became a tool for propaganda. Martinů was called a traitor. He wisely chose not to work in his home country after this.

Martinů was hesitant to leave America, which had supported him. He taught at the Mannes College of Music from 1948 to 1956. He also taught at Princeton University and the Berkshire Music School. At Princeton, he was welcomed by everyone.

He wrote his six symphonies between 1942 and 1953. The first five were written very quickly, from 1942 to 1946. He also composed the Violin Concerto No. 2, Memorial to Lidice for orchestra, and many other pieces. His symphonies were played by most major orchestras in the US. He usually received good reviews from critics.

Some critics who didn't know Martinů said he composed too much, too fast. They thought his music might not be good quality. But musicians and critics who knew him defended him. Olin Downes, a critic, said Martinů was "incapable of an unthorough or conscienceless job." He added that Martinů "works very hard, systematically, scrupulously, modestly." He wrote so much music because he loved it and had to write it. Composer David Diamond was amazed at how Martinů could create a whole orchestral score in his mind while walking.

Some of Martinů's notable students include Burt Bacharach and Alan Hovhaness.

Final Years in Europe (1953–1959)

In 1953, Martinů left the United States for France. He settled in Nice. He finished his Fantaisies symphoniques there. The next year, he composed Mirandolina and a piano sonata. He also met Nikos Kazantzakis and began working on The Greek Passion.

In 1955, he created several important works. These included the oratorio Gilgames, the Oboe Concerto, and the cantata The Opening of the Wells. Charles Munch conducted the first performance of Fantaisies symphoniques in Boston. This work won Martinů a critics' prize. In 1956, he became a composer-in-residence at the American Academy in Rome. He composed Incantation (his fourth piano concerto) and much of The Greek Passion there. He finished The Greek Passion in January 1957.

Even though he never returned to Czechoslovakia, his later music showed a longing for home. His many compositions continued in 1958 with The Parables for orchestra and the opera Ariane. The next year, he saw the first performance of Julietta since its premiere in Prague. He continued composing until his death. These last works included a second version of The Greek Passion, the Nonet, and the cantatas Mikeš from the Mountains and The Prophecy of Isaiah.

Bohuslav Martinů died of gastric cancer in Liestal, Switzerland, on August 28, 1959. His body was later moved and buried in Polička, Czechoslovakia, in 1979.

His Music

Martinů was a very productive composer. He wrote almost 400 pieces of music! Many of his works are still performed and recorded today. These include his oratorio The Epic of Gilgamesh (1955), his six symphonies, and nearly thirty concertos. He wrote four violin concertos, eight pieces for solo piano, four cello concertos, and many others. He also wrote an anti-war opera called Comedy on the Bridge. His chamber music includes eight string quartets and three piano quintets. He also wrote a flute sonata and a clarinet sonatina.

A special thing about his orchestral music is that it almost always includes a piano. Many of his orchestral works have an important part for the piano. Most of his music from the 1930s to the 1950s was in a neoclassical style. But in his last works, his style became more free and spontaneous. You can hear this by comparing his Fantaisies symphoniques (Symphony No. 6) with his earlier symphonies from the 1940s.

One of Martinů's lesser-known works features the theremin. This is an electronic musical instrument. Martinů started working on his Fantasia for theremin, oboe, string quartet and piano in 1944. He finished it on October 1. He dedicated it to Lucie Bigelow Rosen, who asked him to write it. She was the theremin soloist when it was first performed in New York in 1945.

His opera The Greek Passion is based on a novel by Nikos Kazantzakis. His orchestral work Memorial to Lidice was written to remember the village of Lidice. This village was destroyed by the Nazis in 1942. Martinů finished this piece in August 1943 in New York. It was first performed there in October of that year.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Bohuslav Martinů para niños

In Spanish: Bohuslav Martinů para niños

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |