Nikos Kazantzakis facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Nikos Kazantzakis

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

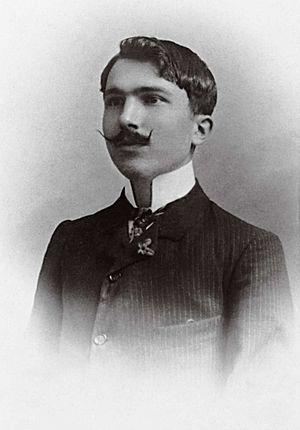

| Born | 2 March 1883 Kandiye, Crete, Ottoman Empire (now Heraklion, Greece) |

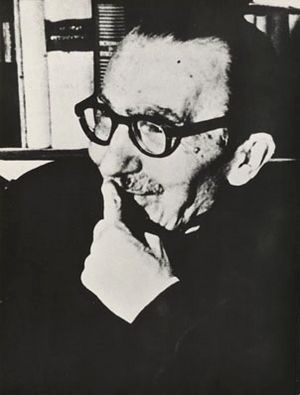

| Died | 26 October 1957 (aged 74) Freiburg im Breisgau, West Germany (now Germany) |

| Occupation | Poet, novelist, essayist, travel writer, philosopher, playwright, journalist, translator |

| Nationality | Greek |

| Education | University of Athens (1902–1906; J.D., 1906) University of Paris (1907–1909; DrE, 1909) |

| Signature | |

|

|

Nikos Kazantzakis (Greek: Νίκος Καζαντζάκης [ˈnikos kazanˈd͡zacis]; born March 2, 1883 – died October 26, 1957) was a famous Greek writer. Many people consider him one of the most important figures in modern Greek literature. He was nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature nine times!

Kazantzakis wrote many well-known novels. These include Zorba the Greek (published in 1946), Christ Recrucified (1948), Captain Michalis (1950), and The Last Temptation of Christ (1955). He also wrote plays, travel books, and philosophical essays. His books became very popular around the world, especially after Zorba the Greek (1964) and The Last Temptation of Christ (1988) were made into movies.

He also translated many important works into Modern Greek. These include the Divine Comedy, Thus Spoke Zarathustra, On the Origin of Species, and Homer's famous poems, the Iliad and the Odyssey.

Contents

About Nikos Kazantzakis

Nikos Kazantzakis was born in 1883 in Kandiye, which is now called Heraklion. This city is on the island of Crete. At that time, Crete was not yet part of Greece. It was still under the rule of the Ottoman Empire.

From 1902 to 1906, Kazantzakis studied law at the University of Athens. After that, he went to the Sorbonne in 1907 to study philosophy. There, he was greatly influenced by the ideas of a philosopher named Henri Bergson. When he returned to Greece, he started translating important philosophical books. In 1914, he met another Greek writer, Angelos Sikelianos. They traveled together for two years, exploring places where Greek Orthodox Christian culture was strong.

Kazantzakis married Galatea Alexiou in 1911, but they divorced in 1926. He later met Eleni Samiou in 1924. They started a relationship in 1928 and got married in 1945. Eleni helped him a lot with his work. She typed his drafts, traveled with him, and managed his business. They were married until his death in 1957.

His Travels and Ideas

Between 1922 and his death in 1957, Kazantzakis traveled all over the world. He visited many cities like Paris, Berlin, Rome, and Moscow. He also traveled to countries like Spain, Cyprus, Egypt, China, and Japan.

While he was in Berlin, he learned about communism and admired Vladimir Lenin. However, he never fully joined the communist party. He visited the Soviet Union and saw the rise of Joseph Stalin. This made him lose faith in Soviet-style communism. Around this time, his earlier strong nationalistic beliefs changed. He started to believe in ideas that were more universal and applied to all people. As a journalist in 1926, he even interviewed famous leaders like Miguel Primo de Rivera and Benito Mussolini.

During World War II, he was in Athens and translated Homer's Iliad. In 1945, he became the leader of a small political party on the left side of politics. He even served in the Greek government as a Minister for a short time. In 1946, he became the head of the UNESCO Bureau of translations. This organization helps translate books from one language to another. However, he left this job in 1947 to focus on his writing. Most of his famous books were written in the last ten years of his life.

In 1946, the Society of Greek Writers suggested that Kazantzakis should receive the Nobel Prize for Literature. In 1957, he lost the prize to Albert Camus by just one vote. Camus later said that Kazantzakis deserved the honor much more than he did. Overall, Kazantzakis was nominated for the Nobel Prize nine times!

His Final Journey

In late 1957, even though he was sick with leukemia, he went on one last trip to China and Japan. He became very ill on his flight back and was taken to Freiburg, Germany, where he passed away. He is buried in his hometown of Heraklion, on the highest point of the city walls. From there, he can look out over the mountains and the sea of Crete.

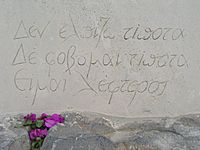

His famous epitaph (the words on his grave) reads: "I hope for nothing. I fear nothing. I am free." This short but powerful saying shows his philosophical belief in freedom and not being afraid.

In 2007, a special €10 Greek coin was made to honor the 50th anniversary of his death. His picture is on one side of the coin, and his signature is on the other.

His Literary Work

Kazantzakis's first published work was a story called Serpent and Lily in 1906. He used the pen name Karma Nirvami for this work. When he studied in Paris in 1907, he was greatly influenced by the philosopher Henri Bergson. Bergson believed that we truly understand the world by combining intuition, personal experience, and logical thinking. This idea of mixing logic with feelings became very important in many of Kazantzakis's later stories and characters.

In 1909, he wrote a play called Comedy. This play explored themes of existentialism, which is a philosophy about finding meaning in life. This was even before the main existentialist movement became popular after World War II. After his studies, he wrote a tragedy called "The Master Builder," based on a popular Greek folk story.

For several decades, from the 1910s to the 1930s, Kazantzakis traveled widely. He explored Greece, much of Europe, North Africa, and parts of Asia. These journeys allowed him to experience different philosophies, ways of life, and people. All of these experiences influenced his writing. He often wrote to his friends about his influences, mentioning Sigmund Freud, the philosophy of Friedrich Nietzsche, Buddhist ideas, and communist beliefs.

Kazantzakis started writing The Odyssey: A Modern Sequel in 1924. He finished it in 1938 after fourteen years of writing and revising. This long poem continues the story of Homer's hero, Odysseus, on a new journey after the original poem ends. Like Homer's Odyssey, it has 24 parts and is very long, with 33,333 lines! Kazantzakis felt this poem contained all his wisdom and was his greatest work. However, critics had different opinions. Some praised it as an amazing epic, while others thought it was too proud. Even today, scholars disagree about it. Some critics also felt that Kazantzakis used too many fancy and metaphorical words in this poem and in his other fiction.

Many of Kazantzakis's most famous novels were published between 1940 and 1961. These include Zorba the Greek (1946), Christ Recrucified (1948), Captain Michalis (1953), The Last Temptation of Christ (1955), and Report to Greco (1961).

These stories explore different parts of Greek culture after World War II. They look at religion, national pride, political beliefs, the Greek Civil War, and how men and women were expected to act. They also explore what Kazantzakis believed was Greece's special place in the world, being neither fully Eastern nor Western. He thought Greece's special job was to bring together Eastern feelings with Western logic.

As mentioned earlier, two of his novels, Zorba the Greek and The Last Temptation of Christ, were made into popular movies in 1964 and 1988.

Language Choices

When Kazantzakis was writing, most serious Greek writers used a "pure" form of the Greek language called Katharevousa. This language was created to connect Ancient Greek with Modern Greek and to make Modern Greek "purer." However, using the everyday spoken language, called Demotic Greek, slowly became more popular among writers in the early 1900s.

Kazantzakis chose to write in Demotic Greek. He wanted his writing to connect with the spirit of the common Greek people. He also wanted to show that the everyday spoken language could be used to create beautiful and artistic literary works. He felt it was important to record the way ordinary people spoke, including Greek farmers. He often included their expressions, metaphors, and idioms in his writing so they wouldn't be forgotten. At the time, some scholars criticized his work for not being in Katharevousa, while others praised him for using Demotic Greek.

Some critics have said that Kazantzakis's writing was too fancy, full of hard-to-understand metaphors, and difficult to read, even though it was in Demotic Greek. However, scholars like Peter Bien argue that Kazantzakis took these metaphors and language directly from the farmers he met while traveling in Greece. Bien believes that Kazantzakis used their local phrases to make his stories feel real and to preserve these unique ways of speaking.

His Views on Society

Throughout his life, Kazantzakis believed that "only socialism as the goal and democracy as the means" could solve the big problems of his time. He thought that socialism, which means a social system where no one can take advantage of another person, should guarantee freedom for everyone. He wanted socialist parties around the world to work together to achieve "socialist democracy."

Kazantzakis was not liked by the right-wing political groups in Greece. They called him "immoral" and a "Bolshevik troublemaker," and even accused him of being a "Russian agent." However, the Greek and Russian Communist parties also didn't fully trust him, calling him a "bourgeois" (middle-class) thinker. But after his death in 1957, the Chinese Communist party honored him as a "great writer" and a "devotee of peace." After World War II, he was briefly the leader of a small Greek leftist party. In 1945, he also helped start the Greek-Soviet friendship union.

His Religious Beliefs

Kazantzakis was a very spiritual person, but he often struggled with his religious faith, especially his Greek Orthodoxy. He was baptized Greek Orthodox as a child and was fascinated by the lives of saints from a young age. As a young man, he took a month-long trip to Mount Athos, a very important spiritual center for Greek Orthodoxy.

Most experts on Kazantzakis agree that his struggle to find truth in religion and spirituality was a main theme in many of his works. Some of his novels, like The Last Temptation of Christ and Christ Recrucified, deeply question Christian ideas and values. As he traveled, he was influenced by different philosophies, cultures, and religions, like Buddhism. This made him question his Christian beliefs.

While he never said he was an atheist, his public questioning of basic Christian values caused problems with some members of the Greek Orthodox Church and many critics. Scholars believe that his difficult relationship with some church leaders came from his questioning. One scholar, Darren Middleton, explains that while most Christian writers focus on God's unchanging nature and Jesus's divinity, Kazantzakis focused on Jesus's humanity and how God could be "redeemed" through human effort. This shows his unique way of interpreting traditional Orthodox Christian beliefs.

Many Orthodox Church clergy condemned Kazantzakis's work and tried to have him excommunicated (removed from the church). His famous reply to them was: "You gave me a curse, Holy fathers, I give you a blessing: may your conscience be as clear as mine and may you be as moral and religious as I" ("Μου δώσατε μια κατάρα, Άγιοι πατέρες, σας δίνω κι εγώ μια ευχή: Σας εύχομαι να ‘ναι η συνείδηση σας τόσο καθαρή, όσο είναι η δική μου και να ‘στε τόσο ηθικοί και θρήσκοι όσο είμαι εγώ"). Even though the top leaders of the Orthodox Church rejected the excommunication, this event showed the ongoing disapproval from many Christian authorities regarding his political and religious views.

Today, many scholars do not see Kazantzakis's work as disrespectful or blasphemous. Instead, they argue that he was following a long tradition of Christians who openly struggled with their faith. They believe that through his doubts, he developed a stronger and more personal connection to God. Some scholars even suggest that Kazantzakis's way of interpreting Christianity, which was more personal, was ahead of its time and has become more popular since his death.

In 1961, Ecumenical Patriarch Athenagoras, a very important leader of the Orthodox Church, declared in Heraklion: “Kazantzakis is a great man and his works grace the Patriarchal library.”

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Nikos Kazantzakis para niños

In Spanish: Nikos Kazantzakis para niños