Rusty patched bumble bee facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Rusty patched bumble bee |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| worker of B. affinis | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Class: | Insecta |

| Order: | Hymenoptera |

| Family: | Apidae |

| Tribe: | Bombini |

| Genus: | Bombus |

| Subgenus: | Bombus |

| Species: |

B. affinis

|

| Binomial name | |

| Bombus affinis Cresson, 1863

|

|

|

|

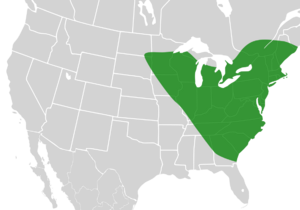

| The past range of Bombus affinis | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The rusty patched bumble bee, also known as Bombus affinis, is a type of bumblebee that lives only in North America. In the past, you could find these bees across the eastern and upper Midwest parts of the United States, stretching north into Ontario and Quebec in Canada, south to Georgia, and west to the Dakotas. Sadly, their numbers have dropped in 87% of the places they used to live. Because of this big decline, the United States Fish and Wildlife Service added the rusty patched bumble bee to the list of endangered species on January 10, 2017. This made it the first bee in the continental United States to be listed as endangered.

Rusty patched bumble bees are quite large. Like other bumblebees, they live in groups with a queen and many workers, which is called being eusocial. Most of their nests are built underground, often in old burrows made by rodents. While nests in labs can have up to 2,100 bees, wild nests are usually much smaller. These bees eat nectar and pollen from many different plants, such as Abelia grandiflora, Asclepias syriaca, and Linaria species. Their nest smells very similar to that of another bee, Bombus terricola, which helps protect them from animals that might want to eat them or parasites.

Contents

About the Rusty Patched Bumble Bee

What's in a Name?

The rusty patched bumble bee, B. affinis, belongs to a group of bees called Apinae. It is most closely related to B. franklini, another bumble bee found only in North America. B. affinis is one of about 250 bumblebee species worldwide in the genus Bombus. About 50 of these species live in the US and Canada. Unlike many other Bombus bees, the worker bees and queens of B. affinis have different color patterns, which helps people tell them apart.

How to Identify Them

Rusty patched bumble bees come in different sizes and colors depending on if they are queens, workers, or males.

Queens and Workers

Queens are the largest, measuring about 20 to 22 millimeters (about 0.8 to 0.9 inches) long and 9 to 11 millimeters (about 0.35 to 0.43 inches) wide. Workers are smaller, usually 10 to 16 millimeters (about 0.4 to 0.6 inches) long and 6 to 9 millimeters (about 0.24 to 0.35 inches) wide. Both queens and workers have black hair on their heads, most of their legs, and the bottom of their bellies. They also have mostly yellow hair on the top part of their bellies, except for a small black section near the very end.

Workers have a mix of yellow and black hairs near where their wings attach, forming a "V" shape. They also have a special rusty-colored patch of hair in the middle of their belly, which gives them their name! So, while queens and workers share some colors, their size and the rusty patch help tell them apart. All rusty patched bumble bees have shorter tongues than other bumblebee species. Because of their size and furry look, they are sometimes confused with other bumblebees like B. citrinus, B. griseocollis, B. perplexus, and B. vagans.

Males

Male rusty patched bumble bees are usually a bit larger than workers, measuring about 13 to 17.5 millimeters (about 0.5 to 0.7 inches) long. They have some off-white or pale hairs on top of their heads. Their bellies are usually yellow, but sometimes they have black streaks across the top. Males can even have pale yellow hair on their bellies, which is different from the brighter yellow seen on workers and queens.

Where They Build Nests

Rusty patched bumble bees usually build their nests underground in places like ditches, wetlands, and fields. Sometimes, they build nests above ground in clumps of grass and soil, especially if there aren't many open grasslands. One time, a B. affinis nest was even found inside an old armchair left outside! When nests are underground, they are typically about 16 to 18 inches (40 to 45 cm) deep in soft soil.

Where Rusty Patched Bumble Bees Live

The rusty patched bumble bee needs three different types of places to live: one for finding food, one for nesting, and one for hibernating. These places need to be close to each other, which makes this bee very sensitive to changes in its environment. They prefer a mild climate and can even handle colder temperatures that most other bumblebees can't. They have been found in high places, up to 1,600 meters (about 5,250 feet) above sea level.

Rusty patched bumble bees visit many different areas to find food, including sand dunes, farms, marshes, and wooded areas. They actively look for food from April to October, so they need flowers to bloom for a long time. Their nests look very similar to those of other bee species, making them hard to find. However, the queen and workers work together to make individual cells and honey pots from wax. We don't know much about where they hibernate. Queens overwinter (spend the winter), likely underground or burrowed into rotting logs to survive.

In the past, the places where B. affinis lived were common, but their habitat has shrunk a lot recently. This is probably because of more land being developed and used for farming. Until the 1980s, the rusty patched bumble bee was one of the most common bumblebees in southern Ontario, Canada. Since then, their numbers have dropped sharply, and they are now hard to find in their usual areas. The last time they were seen in Ontario was in Pinery Provincial Park in 2009, even though many surveys were done. The Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources has started a project to help protect this species and its important habitats in Pinery Provincial Park.

Scientists believe several things have caused their population to decline:

- Diseases spreading from other bee species.

- Pesticide use.

- Habitat fragmentation (when their living areas are broken into smaller pieces) and loss.

Surveys from 2001 to 2008 found B. affinis populations only in Illinois, Iowa, Maryland, and southern Ontario. Bell Bowl Prairie in Illinois is a known home for B. affinis. Sadly, part of it was destroyed in March 2023 to make way for an expansion of the Chicago Rockford International Airport.

Life Cycle of a Colony

Starting and Growing a Colony

New rusty patched bumble bee colonies begin in the spring and die out in the fall. These bees actually wake up earlier than most other Bombus species and keep looking for food even after others have started hibernating.

The first to emerge are the solitary queens. They search for a good place to start a new colony and collect nectar and pollen to feed their future babies. The queen uses sperm she saved from mating the previous fall to fertilize her eggs. Eggs hatch about four days later, but it takes up to 5 weeks for them to become fully grown adults. This time depends on the temperature and how much food is available.

In the first few weeks after laying eggs, the queen is the only one feeding her young. But soon, her female worker offspring start collecting food for the colony, getting ready for more babies. Once the workers can take care of the nest, the queen can focus on laying more eggs. Around the middle of summer, when there are enough workers, the queen starts producing males and new queens. Colonies can have anywhere from 50 to 400 bees, though colonies raised in labs can grow much larger, with up to 2,100 members.

Colony Decline

Around mid-summer, any bees that can reproduce leave the nest and start mating. The number of new queens that can be produced depends a lot on how much nectar and pollen the colony can gather. If there isn't enough food, fewer new queens will be born. Since only new queens can start new colonies, the success of future generations depends on how many queens are produced.

After mating, new queens rest and go into diapause, which is like hibernation for the winter. Male bees and workers die as the weather gets colder, and eventually, they all die when winter arrives. So, colonies usually live for about 4–5 months, depending on the weather. Queens sometimes die at different times during the colony's life, which can leave a colony without a leader. Queens typically live for about 77 days on average.

How They Interact with Other Species

Parasites

The rusty patched bumble bee is often bothered by another bee species called Bombus bohemicus, which is a parasite. B. bohemicus wakes up from hibernation shortly after B. affinis and looks for their established nests. Scientists think the female B. bohemicus can find host nests by their smell from a distance. They fly low to the ground, looking carefully near leaves and debris, to find the nest entrance, then confirm it by smell.

After getting into the nest, B. bohemicus lives alongside the queen and workers. It tries to raise its own young, which need help from the host workers. Larger nests have more workers to defend them, so B. bohemicus often invades smaller nests, which means they stay in these smaller nests for a longer time. B. bohemicus is usually found only in the nests of B. affinis and B. terricola, where it is often tolerated if it goes unnoticed. However, B. affinis bees have been known to eat the parasite's eggs (called oophagy), throw out larvae, or even kick out the parasite in response to its presence. If B. bohemicus tries to invade the nests of other bee species by mistake, the queen of that nest will attack it, often leading to its death.

What They Eat

Rusty patched bumble bees eat nectar and pollen from many different plants, including Lobelia siphilitica, Linaria vulgaris, and Antirrhinum majus. Recent research from 2022 showed that B. affinis often visits flowers from plants like Monarda, Eutrochium, Veronicastrum, Agastache, and Solidago. This research helps people know which plants to grow to help save these bees.

A plant called Dutchman's breeches (Dicentra cucullaria) relies heavily on B. affinis for its reproduction. The flower's shape and how it's pollinated show that it's perfectly suited for foragers like B. affinis, which can separate the flower's outer and inner petals. The bees then use their front legs to expose the parts of the flower that hold pollen. After that, they use their middle legs to sweep pollen forward before flying back to their colony with the pollen. This way, as the bees move from plant to plant, Dutchman's breeches gets pollinated, and B. affinis gets its food. This way of collecting pollen is very similar to how Apis bees (honey bees) do it, though Apis bees are lighter and find it a bit harder to get into these flowers.

Diseases They Face

The rusty patched bumble bee can get sick from a tiny organism called Apicystis bombi, which is a type of protozoa. This disease affects about 3% of all B. affinis bees and is especially common in Ontario. A. bombi first infects the bee's gut and then spreads throughout its body. While we don't fully understand how it spreads, A. bombi causes many problems, including more worker bees dying and preventing new colonies from forming. It also stops queens from developing their ovaries and shortens their lives.

This disease likely came to North America from commercial B. terrestris bees in early 2005 or 2006. These bees invaded northern Patagonia, Argentina, from Europe. In Europe, only about 6-8% of bees show signs of this infection. However, for European bees living in Patagonia, the infection rate can be as high as 50% in some species. Because of this, experts are worried that A. bombi could be very harmful to several bumblebee species, including B. affinis.

Why They Are Important to Farms

The rusty patched bumble bee plays a big role in farming. This species pollinates up to 65 different types of plants and is the main pollinator for important food crops like cranberries, plums, apples, onions, and alfalfa. These crops are vital for people to eat every day. They also provide food for birds and mammals that eat their fruits. Some plants pollinated by B. affinis, such as Aralia and Spiraea, are used as medicine by the First Nations, who are aboriginal peoples of Canada. So, the recent decline of B. affinis could have wide-ranging effects on nature, the economy, and cultural traditions.

In 2008, three main reasons were reported for the decline of B. affinis' role in agriculture:

- Disease Spread: Many bumblebees used in commercial businesses carry harmful parasites that can spread to wild B. affinis populations nearby. This often kills the bees and has also led to the decline of B. terricola and B. impatiens.

- Pesticide Use: New types of pesticides also harm B. affinis populations. Neonicotinoid pesticides are often used to control pests on crops and lawns, but they are also poisonous to bees. Since B. affinis builds its nests underground, they are especially at risk when these pesticides are used on lawns.

- Habitat Loss: More cities and industries mean that natural habitats are being lost. While other species, like B. bimaculatus (the two-spotted bumble bee), have adapted well to city environments, B. affinis has not. It's not yet known if the reduction of native food plants specifically has affected B. affinis.

See also

- List of bumblebee species

| Madam C. J. Walker |

| Janet Emerson Bashen |

| Annie Turnbo Malone |

| Maggie L. Walker |