Brown v. Board of Education II facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Brown v. Board of Education II |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Argued April 11–14, 1955 Decided May 31, 1955 |

|

| Full case name | Oliver Brown, et al. v. Board of Education of Topeka, et al. |

| Citations | 349 U.S. 294 (more) |

| Prior history | Supreme Court ruled for Brown, 347 U.S. 483 (1954) |

| Holding | |

| Schools must obey the original Brown ruling and de-segregate, but not immediately. Federal courts will supervise de-segregation. | |

| Court membership | |

| Case opinions | |

| Majority | Warren, joined by all other Justices |

| Laws applied | |

| Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution | |

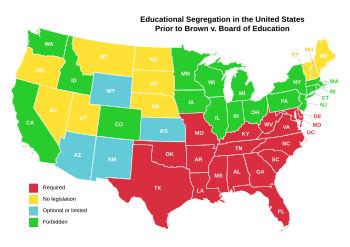

Brown v. Board of Education II (often called Brown II) was an important Supreme Court case decided in 1955. One year before, the Supreme Court had ruled in Brown v. Board of Education. That ruling made racial segregation (keeping Black and white students separate) illegal in public schools.

However, many schools, especially in the South, did not follow this rule right away. They still kept Black and white students apart. In Brown II, the Supreme Court told these schools they had to integrate. This meant they had to allow Black children into all schools. The Court said they must do this "with all deliberate speed."

Brown II also gave rules for how schools should desegregate. It explained how the United States government would make sure schools followed the order.

Contents

Why Brown II Was Needed

After the Supreme Court made its first decision in the original Brown case in 1954, it knew there would be challenges. Segregation in American schools had been around for hundreds of years. The Court understood it would be hard to get states to follow the new rule and desegregate their schools.

Also, the first Brown ruling did not tell states how to end segregation. It also did not give a deadline for when schools needed to desegregate. These were important details the Supreme Court needed to decide in Brown II.

Cases Heard Together

When the Supreme Court decided the first Brown case in 1954, it combined Brown with four other lawsuits. The Court decided all five cases at once. It called them all Brown v. Board of Education.

So, in Brown II, the Court was again making a decision about these five different cases:

- Brown v. Board of Education

- Bolling v. Sharp (from Washington, D.C.)

- Briggs v. Elliot (from South Carolina)

- Davis v. County School Board of Prince Edward County (from Virginia)

- Gebhart v. Belton (from Delaware)

Key Questions for the Court

The Supreme Court had to answer a few important questions in Brown II:

- What rules should the Court set to make sure schools desegregated?

- What rules should the Court set about when schools had to desegregate?

- If schools had violated Black students' rights by not following the first Brown decision, what should happen? What could the Court do to fix the problem?

Arguments Presented

The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) had lawyers who won the first Brown case. They argued that school desegregation should start right away.

However, the states argued that desegregating immediately would be too difficult and expensive. They said they needed more time to make the changes.

The Court's Decision

The Supreme Court made a unanimous decision (9-0). It ordered states to start trying to obey the first Brown decision. They had to begin making plans to integrate their schools.

But the Court did not order schools to integrate right away, as the NAACP wanted. It also did not set a clear deadline for when schools had to be fully desegregated. In the Court's main opinion, Chief Justice Earl Warren wrote that states should integrate "with all deliberate speed."

Many people were unsure what "with all deliberate speed" truly meant. It also meant that the Court was not giving immediate help to the Black students in the Brown lawsuits. Legal expert Steven Emanuel explained that the Court likely feared the chaos and violence that could happen if desegregation was forced to happen instantly.

Instead of ordering immediate desegregation, the Court created a slower plan. It gave federal district courts the power to oversee whether schools were desegregating. Justice Warren wrote that these courts would make sure schools made a "prompt and reasonable start" toward obeying Brown.

Impact of the Decision

Brown II made it clear that schools in the United States would eventually have to desegregate. It also created a process to make sure schools integrated. Federal district courts gained the power to watch over schools, control how long they had to desegregate, and punish them if they refused.

However, many states, especially in the South, were able to avoid integrating their schools for years. This was because Brown II did not set a specific deadline. Justice Warren's phrase "with all deliberate speed" was vague. It could be understood in many ways. States and schools that did not want to integrate used this vagueness as an excuse to delay letting Black students into their schools.

The Griffin Case Example

For example, based on the Brown II ruling, a federal district court said that Prince Edward County, Virginia, did not have to desegregate its schools right away. Several years later, in 1959, a federal court of appeals ordered the county to start desegregating.

Prince Edward County responded by refusing to fund (give money to) its public schools. With no money, the schools had to close. They stayed closed for five years, from 1959 to 1964.

During this time, Prince Edward County helped white students go to white-only private schools. Black students could not go to school at all, unless their families moved to a different county.

Finally, in 1964, the United States Supreme Court ruled that what Prince Edward County was doing was unconstitutional. The Court ordered the schools to reopen without segregation.

Related Pages

- Brown v. Board of Education

- Equal Protection Clause of the Fourteenth Amendment to the United States Constitution (this part of the Constitution helped make school segregation illegal)

- Racial segregation in the United States

| Jessica Watkins |

| Robert Henry Lawrence Jr. |

| Mae Jemison |

| Sian Proctor |

| Guion Bluford |