Bungi dialect facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Bungi |

|

|---|---|

| Bungee, Bungie, Bungay, Bangay, the Red River Dialect | |

| Native to | Canada |

| Region | Red River Colony and Assiniboia, present-day Manitoba |

| Native speakers | approximately 5,000 in 1870; estimated less than 200 in 1993; potentially extinct (date missing) |

| Language family |

Indo-European

|

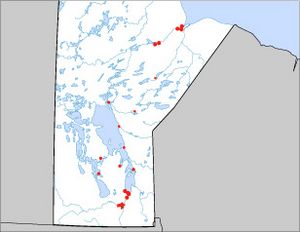

Geographical distribution of Bungee

|

|

Bungi (also called Bungee, Bungie, Bungay, Bangay, or the Red River Dialect) was a special way of speaking English. It was used by the Red River Métis people in what is now Manitoba, Canada. These Métis had Scottish roots.

Bungi was a mix of many languages. It took words and sounds from Scottish English, the Orcadian dialect of Scots, Norn, Scottish Gaelic, French, Cree, and Ojibwe.

Over time, Bungi slowly changed. It became more like standard Canadian English. In 1870, about 5,000 Métis spoke Bungi. But by the late 1980s, only a few older people still knew it. Today, Bungi has very few speakers, if any. It might even be completely gone.

Bungi was spoken in the Lower Red River Colony. This area stretched from The Forks (where the Red and Assiniboine Rivers meet) to Lake Winnipeg. This is where many retired Hudson's Bay Company workers from England and Scotland settled.

Contents

What is Bungi?

How the Name is Spelled

Over the years, Bungi has been spelled in many ways. People often just called it the "Red River Dialect." Today, "Bungi" is the most common and preferred spelling.

Why it's Called Bungi

The name "Bungi" comes from words in other languages. It might come from Ojibwe: bangii (Ojibwe) or Cree: pahkī (Cree). Both words mean "a little bit." Sometimes, people used the term "Bungi" in a slightly negative way.

Bungi is unique because English was often a second language for its speakers. This includes both the Scottish immigrants and the First Nations people who helped create the dialect.

Is Bungi a Language or a Dialect?

Some people, like Brian Orvis from Selkirk, Manitoba, believed Bungi was its own language. He said that Bungi speakers did not like being recorded. This was because of First Nations values. These values teach that people should not draw attention to themselves. This made it hard to study Bungi. Speakers would often say they did not know the language.

Who Were the Bungi People?

The word "Bungi" did not just mean a way of speaking. It also referred to a specific group of Métis. These Métis had Scottish family backgrounds. Early records show that British people, especially those from the Hudson's Bay Company, used "Bungee" to describe the Saulteaux people. Later, around the early 1900s, the word "Bungi" started to mean people with both Scottish and First Nations heritage.

How Bungi Sounded

One of the most special things about Bungi was its phonology. This means its sound system and how words were pronounced. The way people's voices sounded was also different. Most Bungi words came from English. But it also borrowed words from Gaelic, Cree, Ojibwa, and other languages.

Many researchers have studied Bungi. Margaret Stobie visited communities where Bungi was spoken. In 1971, she wrote that Bungi was the English dialect of people whose families came from the Scottish Highlands. Eleanor Blain did a very detailed study of Bungi. She found that people had very negative feelings about Bungi. This likely helped it disappear. Her study showed Bungi in its final stages. It was already becoming much more like standard Canadian English.

Bungi had a special rhythm, like Gaelic. It also had unique ways of stressing syllables. Speakers would often repeat nouns and pronouns in a sentence. For example, they might say, "My brother is coming, him." The sounds of some letters were also different. In Cree, there is no difference between "he" and "she." This meant Bungi speakers sometimes used "he" and "she" interchangeably. For example, "My wife he is going to the store."

Bungi also borrowed phrases directly from other languages. The common Bungi greeting, "I'm well, you but?" came straight from Cree. Bungi speakers also said that Bungi used Cree vowels and Scots consonants. It often followed Cree sentence structure.

Why Bungi Disappeared

People started worrying about Bungi disappearing before 1938. Letters in the Winnipeg Evening Tribune showed this concern. Some writers believed Bungi would be gone in one generation.

Eleanor Blain's research in 1989 looked at why Bungi disappeared. She found that Bungi-speaking families were sometimes left out. Their family histories were not always in local books. They might be given tasks away from fun events. Some people tried to hide their Indigenous background. They felt ashamed of how they sounded when they spoke Bungi. Blain also noted that Bungi was always changing. It was becoming more and more like the local standard English.

Another researcher, Swan, also wrote about the unfair treatment of Bungi speakers. She suggested that Anglo-Métis Manitoba Premier John Norquay might have spoken Bungi. He was born near St. Andrews in the Red River Colony. But by the time he became a politician, he had likely changed his accent.

The negative feelings towards Bungi speakers and the changing language environment led to this unique dialect disappearing.

Who Studied Bungi?

Many experts studied Bungi to learn about it. The main people who documented this dialect were Eleanor M. Blain, Francis "Frank" J. Walters, Margaret Stobie, and Elaine Gold. Osborne Scott also helped us understand Bungi.

Examples of Bungi

An Example from J. J. Moncrieff

In 1936, an article called Red River Dialect was published. The author, J. J. Moncrieff, used the pen name "Old Timer." He included a letter with some Bungi in it.

I met a "nattive" from down the river Clandeboye way yesterday on the streets. We chatted of "ould" times. He relapsed into the lingo and I mentioned the number of fisherman caught on the ice. "Yes," he said, "what a fun the peppers are having about it. I mind when I was a small saver, my faather and some of the byes round out the ice and sate, our nates. Ould One-Button sayed it was going to be cowld. I think me its the awnly time he was wrong, for by gos all quick like a southwaste wind come up and cracked the ice right off, and first thing quick like we were rite out in the lake whatever. It was a pretty ackward place to een, I tell you. The piece we were all on started rite away for the upsit side of the lake, away for Balsam Bay. We put of sales, blankets and buffalo robs to help us get there quicker like. When we hit the sore, we drov rite off the ice. One of the byes went chimmuck, be we got him out alrite.

We drove up to Selcrick on the cross side and crossed the rivver right at the gutway above St. Peters cherch. Oh yes, bye, we got hom alrite; we had to swim our harses. There was nothing in the pepper about it, whatever. We all had quite a funn about it at the dance that nite.

So long bye

P.S. I thought this would interest you in your ould age bye.

Examples from Osborne Scott

Osborne Scott gave a radio talk about Bungi in 1937. It was later published in the Winnipeg Evening Tribune.

John James Corrigal and WIllie George Linklater were sootin the marse The canoe went apeechequanee. The watter was sallow watefer, but Willie George kept bobbin up and down callin "O Lard save me." John James was topside the canoe souted to Willie and sayed, "Never min the Lard just now, Willie, grab for the willows."

Another story was also shared in the same article:

Willie Brass, Hudson's Bay Co. servant, was an Orkneyman who married an Eskimo woman in the north and retired to the Red River Settlement. He got home from the fort one night a little worse for wear with acute indigestion. He went to bed but kept waking, asking Eliza his wife for a drink of hot water saying "Strick a lite, you'll see I'm dying Eliza, and get me a drink, I'm dying." She did strike a light and got him hot water three or four times. Finally she got fed up and said to him, "Awe Willie I'm just slocked it the lite. Can't you die the daark?"

The Shtory of Little Red Ridin Hood

D. A. Mulligan rewrote the famous story of Little Red Riding Hood. He wrote it as if it were told in Bungi.

Eleanor Blain's Research

In her detailed study, The Bungee Dialect of the Red River Settlement, Eleanor Blain shared many examples of Bungi words and phrases. She also included a written version of a story called This is What I'm Thinkin.

Frank Walters' Audio Recordings

Frank Walters was a historian who wanted to save Bungi heritage. He made a series of audio recordings. These are known as the Bungee Collection.

Notable Bungi Speakers

One famous person who likely spoke Bungi was Manitoba Premier John Norquay.

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |