Consolidation Coal Company (Iowa) facts for kids

The Consolidation Coal Company (CCC) was a big mining company started in Iowa in 1875. The Chicago and North Western Railroad bought it in 1880 to get a steady supply of coal nearby. The company mined coal in Mahaska and Monroe counties in south-central Iowa.

After World War I, the company faced challenges. Some coal was running out, and there was more competition from other countries. Because of these changes, CCC closed its mines and left its main towns by the late 1920s. The company first worked in Muchakinock, Mahaska County, until most of the coal there was gone. In 1900, CCC bought about 10,000 acres (40 km2) of land in southern Mahaska County and northern Monroe County, Iowa.

CCC quickly built a planned town called Buxton in northern Monroe County. They moved their main office there. Buxton was special because it was built as an industrial town in a rural area. The company hired many African-American workers, bringing them from the South. These workers held important jobs in local unions and company towns. Buxton was a busy town until about 1925. At that time, CCC opened new camps closer to its newer mines. Buxton became the largest town in the nation that wasn't officially a city. It was also the biggest coal town west of the Mississippi River.

In 1927, the mine in Buxton closed. By the late 1930s, Buxton was completely empty. The demand for coal changed after World War I. Workers moved to other places and cities across the country. Consolidation's Mine No. 18 in Buxton was likely the biggest bituminous coal mine in Iowa. By 1913, the Buxton UMWA union local had at least 80 percent African-American members. In 1914, Buxton had 5,000 people. It was the largest town in the United States mostly run by African Americans.

Starting in 1880, Consolidation was one of the first big companies in the North to hire many African-American workers. They hired Black workers from mining areas in Virginia, West Virginia, and Kentucky. These workers were kept on even after initial hiring. In Muchakinock and Buxton, Black workers were paid the same as white workers. They also lived in communities where everyone lived together. Because of its importance, the Buxton town site was studied by archaeologists. It was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983.

Contents

What Was Muchakinock?

The town name was also spelled Muchachinock or Muchikinock. People started mining coal along Muchakinock Creek in 1843. Local blacksmiths dug coal from places where it showed along the creek. By 1867, small drift mines were built along the creek. These mines went all the way down to Eddyville, where the creek flows into the Des Moines River. In 1873, the Iowa Central Railroad built a train line along Muchakinock Creek.

The Consolidation Coal Company was formed in 1875. It was a merger of the Iowa Central Coal Company, the Black Diamond Mines of Coalfield in Monroe County, Iowa, and the Eureka Mine in Beacon, Iowa. By 1878, Consolidation Coal Company had 400 employees. In 1880, the Chicago and North Western Railway bought it. This was to make sure they had a local source of fuel.

The coal camp at Muchakinock was about 5 miles (8 km) south of Oskaloosa. It quickly grew into one of the biggest and most successful coal camps in Iowa. Consolidation Mine No. 1 opened in 1873. The Muchachinock US post office was open from 1874 to 1904. Its official name changed to Muchakinock in 1886.

How Did Workers Come to Muchakinock?

In 1880, the company had a disagreement with its workers in Muchakinock. J. E. Buxton, Consolidation's superintendent, sent Major Thomas Shumate to the South. He was to hire African Americans to work. Shumate hired many "colored men" from Virginia. Whole families came with each group. "Bringing these men to the mines, and hiring colored miners was a new thing." The first group arrived in Muchakinock on March 5, 1880. By October 6, 1880, Shumate had brought in six groups.

The company paid the $12 train fare from Virginia to Iowa. This amount was taken out of each miner's monthly wages later. The new African-American employees worked so well that the company kept them. In the years that followed, the company said much of its success came from their hard work. The company paid Black and white workers equally. They also did not allow separate housing or schools in their camps and towns.

In 1884, the Chicago and Northwestern finished a 64-mile (103 km) train line to Muchakinock. By then, Mines 1, 2, 3, and 5 were working in Muchakinock. Mine No. 6 was a shaft mine, newly opened just north of the camp. By 1887, the African-American workers in Muchakinock had formed a group to help each other. Members paid fifty cents a month, or $1 per family. Most of this money paid for health insurance. The rest went into a fund to cover burial costs. The coal company acted as the bank for this group.

By 1893, Consolidation Mines No. 6 and 7 produced 1550 tons of coal per day. They employed 489 men and boys. Mine No. 6 had a 130-foot (40 m) shaft. Mine No. 7 had a 45-foot (14 m) shaft. Both mines worked the same 6-foot (1.8 m) thick coal seam. They used a mining method called room and pillar. Mine No. 8 was three miles (5 km) northwest of Muchakinock.

What Happened During the 1894 Coal Strike?

The Bituminous Coal Miners' Strike of 1894 lasted from late April through May. All of Iowa's coal miners went on strike. However, the miners at Muchakinock and Evans (8 miles north) did not. There was a lot of tension. The company management gave Springfield rifles to Muchakinock's Black miners. By May 28, tension was so high that the Iowa National Guard was sent to Muchakinock. On May 30, large groups of armed strikers gathered. They seemed ready to force the Evans camp to strike. This was planned as the first step to attack Muchakinock. In the end, no shots were fired.

African Americans led many groups in Muchakinock. The "colored" Baptist church was led by Rev. T. L. Griffith. Samuel J. Brown was the first African American to get a bachelor's degree from the State University of Iowa. He was the principal of the Muchakinock public school. B. F. Cooper was one of only two "colored" pharmacists in the state.

Muchakinock reached a peak population of about 2,500 people. But by 1900, most of the coal in the Muchakinock valley was gone. The Consolidation Coal Company opened a new mining camp in Buxton, Monroe County. When Buxton was founded in 1901, many workers and their families moved there. Muchakinock was almost empty by 1904. Today, only acid mine drainage and red piles of shale remain from the mines along Muchakinock Creek.

Buxton: A Special Company Town

As early as 1888, a few small mines were working along Bluff Creek. But this changed around 1900. In 1900 and 1901, the Consolidation Coal Company opened a new mining camp at Buxton. This was in Monroe County. The camp was named by B. C. Buxton after his father, John E. Buxton. John had managed the mines at Muchakinock. The company created a planned community with a grid pattern. They hired architect Frank E. Wetherell to design houses, two churches, and a high school. The US Post Office at Buxton was open from 1901 to 1923.

Many Black workers moved here from Muchakinock. After a strike by white miners, the company hired more Black workers from mining areas in the South. The town had many different ethnic groups. There were white immigrants from Slovakia, Sweden, Austria, Ireland, Wales, and England.

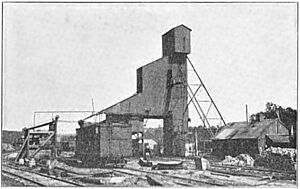

Consolidation Mine No. 10 was about 2 miles (3.2 km) south of Buxton. It had a 119-foot (36 m) deep shaft and a 69-foot (21 m) headframe. The coal seam was 4 to 7 feet (1.2 to 2.1 m) thick. The hoists could lift 4 cars of coal to the surface in a minute. Each car carried up to 1.5 tons of coal. Electric trains were used in the mines. Mine No. 11, opened in 1902, was about a mile south of No. 10. It had a 207-foot (63 m) shaft. By 1908, Consolidation had opened Mine No. 15. All the Buxton mines worked a coal seam about 54 inches (137 cm) thick.

In 1901, Consolidation's miners formed two local unions of the United Mine Workers. They had 493 and 691 members. Local 2106 quickly became the largest union local in Iowa. At that time, Consolidation's mines were mostly worked by "colored miners." In 1913, the Buxton UMWA union local had at least 80 percent African-American members. With 1508 members, Local 1799 at Buxton was the largest UMWA local in the country. African Americans continued running the helpful society they started in Muchakinock. They renamed it the Buxton Mining Colony.

Life in Buxton: A Company Town

Buxton was a classic company town. It was not an official city, and the CCC owned everything. One person said that Mr. Buxton "has not tried to build a democracy. Instead, he has built a system where he is in charge, though a kind one." Booker T. Washington, a famous educator, said that justice in Buxton was "done in a rather quick, frontier way." He said it reminded him of how things were done in some old Western towns.

The Consolidation Coal Company took a caring, parent-like attitude toward the town. In 1908, the town covered about one square mile. It had about 1000 houses, usually with 5 or 6 rooms each. Everything was owned by the coal company. They only rented houses to married couples. Rent was $5.50 to $6.50 per month. Families who caused any trouble were asked to leave in 5 days. The average wage in the mines was $3.63 per day in 1908 (about $123 in 2023). The mines employed 1239 men. Monthly wages varied from $70.80 for daily workers. About 100 men made more than $140 per month. There was no difference in pay between races.

Like in Muchakinock, African Americans held many leadership roles in the town. The US postmaster, school superintendent, most teachers, two justices of the peace, two constables, and two deputy sheriffs were all African American. The Bank of Buxton had deposits of over $106,000 in 1907. Its only cashier was also African American. One of the civil engineers for the mining company was African American. For a short time, The Buxton Eagle was the town's newspaper.

African-American doctors included Edward A. Carter, MD. He was born in Muchakinock and was the first "colored" graduate of the University of Iowa College of Medicine. He came to Buxton as an assistant doctor. He also worked as the company surgeon for the mining company and the Chicago and Northwestern Railway. George H. Woodson and Samuel Joe Brown were African-American lawyers who lived in Buxton for a time. They helped start the Niagara Movement in 1905. This group was a step toward forming the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP).

Richard R. Wright Jr. wrote in 1908:

The relations between the white minority and the black majority are very friendly. No case of attack by a black man on a white woman has ever been heard of in Buxton. Both races go to school together; both work in the same mines, clerk in the same stores, and live side by side."

In the same year, Booker T. Washington wrote that Buxton was "a community of some four or five thousand Colored people... it is a success." He suggested studying Buxton to a textile factory owner.

By 1908, mines 11 and 13 were almost empty. The population of Buxton dropped to about 5000. It was still the largest town in the country with a majority-Black population. It was also the "largest unincorporated city in the nation and the largest coal town west of the Mississippi River." Unlike smaller company towns, Buxton was the main living area for miners. They worked at mines spread out over a large distance. The company ran commuter trains to take the men to the mines.

The coal company gave the YMCA free use of a building worth $20,000. The YMCA had a reading room, library, gym, baths, kitchen, dining room, and a meeting hall. This hall was available for labor unions and other groups. The Buxton YMCA had a rule about race. It did "not allow white men in the membership." However, white men were "allowed to attend the entertainments." The Buxton YMCA offered many adult education programs. These included reading and writing and hygiene classes. They also had public lectures. The YMCA also controlled the Opera House. They kept out "unsuitable and immoral shows."

Like most mining company towns, there was a company store, the Monroe Mercantile Company. This was a big business with 72 employees. Some were paid as much as $68 per month, and many were African Americans. But there was also competition for the company store. Buxton was unusual because it had more than 40 independent businesses. These included a hotel, grocery, general store, meat market, lumber yard, barber shops, tailor, butcher, and clothing stores. Many were run by African Americans.

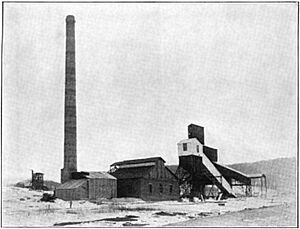

In 1919, Consolidation Mine No. 18 was 12 miles (19 km) southwest of Buxton. It was the most productive coal mine in Iowa. This mine employed 498 men all year. It produced almost 300,000 tons of coal that year. This was more than 5% of the state's total coal production. Mines 16 and 18 worked a coal seam 4 to 7 feet (1.2 to 2.1 m) thick. But after World War I, the demand for Buxton coal went down. Coal from other countries became cheaper. The remains of Mine No. 18 were blown up in 1944.

By the time Mine No. 18 opened, CCC's mining activity had moved 10 miles (16 km) west of Buxton. The company opened new mining camps closer to these mines. Because of this, people moved, and Buxton declined a lot in the 1920s. Its last mine closed in 1927. By 1938, the Federal Writers Project Guide to Iowa said that Buxton was abandoned. It said that the locations of Buxton's old "stores, churches and schoolhouses are marked only by stakes." Every September, hundreds of former Buxton residents met for a reunion at the old town site.

The abandoned Buxton town land is now used for farming. The town site was studied by archaeologists in the 1980s. They looked at the economic and social life of African Americans in Iowa. Because of what they found and Buxton's importance, the archaeological site was added to the National Register of Historic Places. The company town is known as a former "black utopia."

Images for kids