Chatterley Whitfield facts for kids

Chatterley Whitfield Colliery was a very important coal mine in Stoke-on-Trent, England. It was the biggest mine in the North Staffordshire Coalfield. It was also the first mine in the UK to dig up one million tons of coal in a single year!

Today, the colliery buildings are not used and are in very bad condition. They are on a special list called the Heritage at Risk Register. This means they are important historical sites that need help to be saved. In 2019, it was named one of the top ten most endangered buildings in England and Wales.

Contents

- History of the Mine

- Early Mining Days (Before 1863)

- Growing Deeper (1863 to 1876)

- The 1881 Pit Disaster

- Challenges and Recovery (1876 to 1884)

- The 'Golden Age' (1884 to 1920s)

- Modernisation and Records (1920s to 1947)

- Mine Details (Around 1930)

- Later Years and Closure (1947 to 1977)

- The Mining Museum (1977 to 1986)

- Why the Underground Tours Stopped

- The New Experience (1986 to 1993)

- Images for kids

History of the Mine

Early Mining Days (Before 1863)

We don't know exactly when people first started mining coal at Whitfield. But there are records of mining in the nearby area of Tunstall from the late 1200s. Some stories say that monks from Hulton Abbey mined coal here in the 1300s and 1400s. They dug tunnels called 'footrails' from the surface.

In 1750, a man named Ralph Leigh from Burslem collected coal from Whitfield twice a day. He used six horses to carry the coal because the roads were too bad for wagons. Each horse carried about 100-150 kg of coal.

In 1838, a survey of the colliery showed it had an engine house, a coal storage area, a carpenter's shop, and a brickworks. All the buildings and machinery were valued at about £154.

Hugh Henshall Williamson started mining in the Whitfield area around 1853. He probably used existing shallow mine shafts. By 1853, he was working on several coal seams.

In 1854, local coal owners pushed the North Staffordshire Railway to build a new train line. This line, called the Biddulph Valley line, was finished in 1860. It passed very close to Whitfield. Hugh Henshall Williamson quickly built his own railway link from the mine to the new train line. This made it much easier to transport coal.

Growing Deeper (1863 to 1876)

In 1863, one of the mine shafts, called Ragman, was made deeper, reaching 137 metres. At this time, one engine helped lift coal from three different shafts. Coal was brought up in small tubs. Miners also used these tubs to go up and down, which was quite dangerous before proper cages were used.

As the mine got deeper, keeping the air fresh was a big problem. This was especially true because the mine produced a lot of methane gas, which is very explosive. In 1868, miners at Whitfield were still using candles, which was a risky practice.

Hugh Henshall Williamson died in 1867. A group of local businessmen took over the mine, forming the Whitfield Colliery Company Limited. They bought the mine and its land for £40,000. The new owners immediately started improving the mine. They made the Engine Pit deeper and wider. They also gave each main shaft its own steam engine for lifting coal.

In 1873, the Chatterley Iron Company Limited bought the Whitfield Colliery. They needed a good supply of coal for their blast furnaces. The new owners quickly began to develop new coal seams. In 1874, they started making the old Bellringer shaft wider and deeper, aiming for 440 yards (about 400 metres) deep.

The Bellringer shaft was renamed the Institute shaft. The company also deepened another old shaft, naming it the Laura shaft after the owner's daughter. Both shafts were finished in 1876.

The 1881 Pit Disaster

On February 7, 1881, a serious fire and explosion happened at Whitfield. The fire was caused by a blacksmith's furnace underground. The explosion tragically killed twenty-four men and boys.

The explosion caused the Laura Pit to collapse, and that shaft was abandoned. The Institute shaft also had to be partly filled to help put out the fire. An investigation was held, and the mine manager was cleared of charges.

To make up for the lost coal production, the Middle Pit shaft was deepened in 1881. A new shaft, called the Platt Pit, was sunk to replace the Laura shaft. It was completed in 1883.

Challenges and Recovery (1876 to 1884)

As more coal was mined, the company needed better ways to transport it. In 1873, they started building their own private railway line. This line was finished in 1878. It greatly reduced the cost of moving coal from Whitfield to the furnaces.

In 1876, the company faced serious money problems. They had spent a lot of money, and the economy was slowing down. To fix this, they cut costs and closed many smaller pits. The managing director, Mr. Charles J. Homer, disagreed with this plan and resigned. However, the cost-cutting worked, and the company started to recover.

Unfortunately, in 1880, their oil distillery at Chatterley was destroyed by fire.

By 1884, the company was again in financial trouble. It was almost closed down. However, the company's affairs were put under the control of three liquidators. One of them was John Renshaw Wain, whose son, Edward Brownfield Wain, would later lead the company to its most successful period.

The 'Golden Age' (1884 to 1920s)

Edward Brownfield Wain was a key reason for the mine's recovery. He became Undermanager in 1882. He introduced a more efficient way of mining called longwall working. This replaced the older 'pillar and stall' system. He became Colliery Manager in 1886. By 1890, the company was making money again.

In 1890, a new company called Chatterley Whitfield Collieries Limited was formed. This began a huge period of growth for the mine. By 1899, the colliery produced over 950,000 tons of coal. The Chatterley Iron Company, which had owned the mine before, started to decline and closed down.

The mine continued to do well. After a small explosion in 1912, it was clear that more fresh air was needed underground. So, in 1913, they started digging a new ventilation shaft. This shaft was 5 metres wide and 213 metres deep. It was finished in 1914. The building above the shaft, called the heapstead, was made of brick in a unique German design.

This new shaft was named the Winstanley shaft. As a result, two older shafts, the Prince Albert and the Engine Pit, were closed.

Soon after the Winstanley shaft was finished, plans were made for another deep shaft. This new shaft would help reach coal seams that were very far away. Work started in 1914, and the shaft was completed in 1917. It was 585 metres deep and named the Hesketh shaft, after the Chairman of the company. A huge steam engine was installed to lift coal from this shaft.

Modernisation and Records (1920s to 1947)

Before 1915, all coal at Whitfield was dug by hand. But in that year, electric coal cutters and air-powered conveyors were brought in. These machines helped miners dig and move coal more easily.

In 1920, the mine got its first canteen for miners. Work also began on a new lamp room for the heavy electric lamps that were being used more and more.

The late 1920s and early 1930s were tough times for mines and miners. During the general strike of 1926, many trucks came to Whitfield to buy coal. In 1929, the mine only worked for 193 days. During the 1930s Depression, 300 Whitfield miners lost their jobs. Mines had to stop working once they reached their monthly coal limit.

By 1932, all underground transport was done by machines. Most pit ponies were taken out of the mine. Steel supports started to replace wooden ones. Miners at first didn't like steel supports because they didn't creak as a warning before breaking like wood did. But eventually, steel supports were accepted.

In 1934, a new office building was built at Whitfield. Most staff moved there. This also ended the "Pay Train" that brought wages from Tunstall to Whitfield on Saturday afternoons.

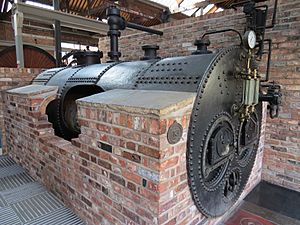

In 1938, a new boiler house with twelve large Lancashire boilers was opened. It was considered one of the best in Britain. In the same year, the Pithead Baths opened. These baths had 3,817 lockers for clean clothes and 3,817 for dirty clothes. This meant miners could wash and change after their shift.

The 1930s were a great time for Whitfield. Over 4,000 men worked there. In 1937, it became the first mine in Britain to dig one million tons of coal in one year. It did this again in 1938.

From 1938 until 1947, not much changed. On January 1, 1947, the mines were taken over by the government and became part of the National Coal Board.

Mine Details (Around 1930)

Here are some interesting facts about Chatterley Whitfield around 1930:

- The Hesketh shaft was 640 yards deep. Its cage could hold six 10cwt tubs of coal.

- The Institute shaft was 440 yards deep. Its cage held four 10cwt tubs.

- The Middle Pit shaft was 240 yards deep. Its cage had three levels, each holding two 8cwt tubs.

- There were 15 large Lancashire boilers to power the mine.

- The mine owned 10 steam locomotives, with names like Katie, Alice, and Dolly.

- They had 290 railway wagons that could carry 12 tons of coal each.

- There were 34 horses and ponies working underground and 8 on the surface.

- The mine had 24 miles of railway tracks.

- They had several motor vehicles, including lorries and an ambulance.

- In 1930, there were 50 miles of underground tunnels that needed to be kept in good repair.

- Chatterley Whitfield was a "wet pit." This meant they had to pump out a lot of water. In 1930, they pumped out about 2.46 million litres of water every 24 hours! This water was then reused for the boilers.

Later Years and Closure (1947 to 1977)

After the mines were taken over by the government in 1947, many changes happened. In 1952, new mine cars and locomotives were used underground at Whitfield. A new system for moving these cars was built on the surface.

In the late 1950s, cheap oil became available from other countries. This meant less coal was needed, and many older mines started to close. Chatterley Whitfield was one of these. Its coal production dropped from over one million tons in 1937 to 408,000 tons in 1965.

Coal stopped being lifted from the Institute shaft in 1955 and from the Middle Pit in 1968. In 1974, it was decided that coal from Whitfield could be mined more easily from a nearby mine called Wolstanton Colliery. An underground tunnel was dug to connect the two mines. In 1977, coal production at Chatterley Whitfield finally stopped.

The Mining Museum (1977 to 1986)

After coal production ended on March 25, 1977, a brave idea was started. A charity decided to turn the colliery into Britain's first underground mining museum! A lot of work was needed to prepare the site. Old buildings were fixed, the underground tunnels were made safe for visitors, and mining machines were repaired. The goal was to show what life was like for miners and to save this important part of history.

In 1979, the Chatterley Whitfield Mining Museum opened. It quickly became very popular, attracting over 70,000 visitors each year. Visitors could go on underground tours.

During this time, the large, cone-shaped pile of waste material (spoil heap) at Chatterley Whitfield was made much smaller. This landscaping work took from 1976 to 1982.

Why the Underground Tours Stopped

Mining in The Potteries area started with many small mines. As it became harder to find coal, mines had to go deeper. Mining also became more expensive as machines were used. So, fewer mines existed, but they became much larger.

Chatterley Whitfield was a big mine in the 1930s, surrounded by other pits. Each mine had its own pumps to keep the tunnels dry. These pumps lowered the water level across the whole area. But over the years, the mines around Chatterley Whitfield closed one by one.

When the Mining Museum opened, visitors went down the Winstanley shaft, 213 metres deep. They explored tunnels at this depth. However, these tunnels were only a small part of the whole mine. The Hesketh shaft went down almost 610 metres! In the 1930s, there were about 50 miles of tunnels.

Near the end of its working life, Chatterley Whitfield was connected to the nearby Wolstanton Colliery by a 4-mile underground tunnel. Wolstanton Colliery had shafts that went down up to 914 metres. Since it was the last working mine in the area, Wolstanton was responsible for pumping water out. This helped keep Chatterley Whitfield dry.

In 1981, Wolstanton Colliery stopped producing coal. After months of clearing out the mine, its pumps were turned off in May 1984. This meant that water would slowly rise to its natural level. It would flood the abandoned tunnels at Wolstanton and then eventually Chatterley Whitfield. The museum couldn't afford the high cost of pumping all that water.

The water would take years to reach the level of the old Chatterley Whitfield tour. But there was another problem: coal gives off methane gas. Methane is a gas formed from ancient plants that became coal. Mining releases this gas. Methane is colourless and highly explosive. If there's too much in the air, it can also reduce oxygen and cause suffocation.

Methane is lighter than air, so it builds up at the top of mine tunnels. In a working mine, large fans keep the air moving and prevent this. But when the fans stop, methane builds up in the abandoned tunnels.

As the water slowly rose after Wolstanton closed, the methane levels were watched carefully. The levels were rising, and they were also affected by the weather. It was decided that all the shafts had to be sealed to trap the methane underground.

Because of the rising water and methane gas, it became unsafe for visitors to go into the old underground workings of Chatterley Whitfield. The solution was to build a new, specially designed mining experience. This new attraction opened on August 20, 1986.

The New Experience (1986 to 1993)

When British Coal seals old mine shafts, they usually fill them right up to the surface. But at Chatterley Whitfield, they knew the museum needed a new underground tour. So, British Coal helped.

First, they plugged two shafts well below the surface with thick concrete. This stopped the gas from rising higher. It also meant the museum could still use the tops of the shafts. One shaft was used to show visitors how miners rode the cage to work. The other showed how coal was lifted.

From the area at the bottom of the pit, the museum started a very unusual project. They built a new mine using some shallow tunnels and an old railway cutting. This new "Experience" was designed to show the history of mining from 1850 to the present day.

The new mining experience lasted until the early 1990s. The museum closed on August 9, 1993, and was placed into the hands of liquidators.

Images for kids

| Shirley Ann Jackson |

| Garett Morgan |

| J. Ernest Wilkins Jr. |

| Elijah McCoy |