City Investing Building facts for kids

Quick facts for kids City Investing Building |

|

|---|---|

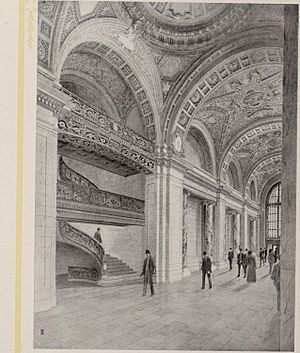

1907 depiction

|

|

| Alternative names | Benenson Building 165 Broadway |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Type | Commercial offices |

| Location | 165 Broadway New York City, US |

| Coordinates | 40°42′35″N 74°00′40″W / 40.709858°N 74.011117°W |

| Completed | 1908 |

| Demolished | 1968 |

| Height | |

| Roof | 486 ft (148 m) |

| Top floor | 32 |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 33 |

| Lifts/elevators | 24 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | Francis H. Kimball |

| Main contractor | Hedden Construction Company |

The City Investing Building was a very tall office building, one of the first skyscrapers, in Manhattan, New York City. It was also known as the Broadway–Cortlandt Building and the Benenson Building. The building was the main office for the City Investing Company. It stood in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan, between Church Street and Broadway. Francis H. Kimball designed the building, and the Hedden Construction Company built it.

Because the land sloped, the City Investing Building looked 32 stories tall from Broadway and 33 stories tall from Church Street. The main part of the building was 26 stories high. A central section rose another seven stories, topped with sloped roofs. The building had an "F" shape from above, with an open space called a light court facing Cortlandt Street. It also had a part that wrapped around a smaller building called the Gilsey Building. Inside, there was a huge lobby that connected Broadway and Church Street. Each upper floor had a lot of space, from about 5,200 to 19,500 square feet.

Construction on the City Investing Building began in 1906, and it opened in 1908. It had about 12 acres of floor space, making it one of New York City's largest office buildings at the time. The City Investing Company built it, but it had several owners over the years. In 1919, Grigori Benenson bought the building and renamed it the Benenson Building. After some financial trouble in the 1930s, it was sold twice. By 1938, it was called 165 Broadway and was updated in 1941. In 1968, the City Investing Building and the nearby Singer Building were torn down. A new, much larger building called One Liberty Plaza was built in their place.

Contents

Where Was the Building Located?

The City Investing Building was in the Financial District of Lower Manhattan. It faced Church Street to the west, Cortlandt Street to the north, and Broadway to the east. The building was 209 feet long on Cortlandt Street, 109 feet long on Church Street, and 37.5 feet long on Broadway. It was 313 feet deep and stood next to the Singer Building on its south side. The land sloped downwards from Broadway to Church Street. This meant the basement was above ground on the Church Street side but below ground on the Broadway side.

The building's northeast part wrapped around a smaller building called the Gilsey Building. This building was at the corner of Cortlandt Street and Broadway. The Gilsey Building was 56.5 feet long on Broadway and 106 feet long on Cortlandt Street. The City Investing Company, the original owner, had a long-term lease for the Gilsey Building. They planned to tear it down later to make the City Investing Building even bigger. There was only a 10-foot gap between the City Investing Building and the Singer Tower. This small gap was because of a design choice by the Singer Building's architect, Ernest Flagg.

How Was the Building Designed?

Francis H. Kimball designed the City Investing Building. The Hedden Construction Company was the main builder. Other companies handled specific parts, like the foundation, steel frame, and plumbing. The steel for the building was made by the American Bridge Company.

The outside of the City Investing Building had three main parts. There was a base with four stories and a raised basement. Above that was a tall middle section, or "shaft," with 21 stories and a decorative top edge called a cornice. The very top part, or "capital," had six stories and an attic. The building rose 486 feet above Broadway. Different sources described the building as having 32, 33, or even 34 stories, depending on how they counted the attic and the different ground levels.

What Did the Building Look Like?

The City Investing Building was mostly shaped like an "F" when viewed from above. The two "arms" of the "F" on the north side created a 40-by-65-foot open space called a light court on Cortlandt Street. This light court started above the second floor. A section of the building also stretched east to Broadway, between the Gilsey and Singer buildings. The main part of the building had 25 usable stories above Broadway, plus a 26th story inside the cornice. The "arms" on Cortlandt Street were like narrow towers, ending at the 26th story. The very center of the building rose six more stories, with a fancy sloped roof made of copper.

The bottom five stories of the building were covered with light-colored stone. The middle and top sections were decorated with white brick and terracotta. Porcelain and enamel bricks were used because they wouldn't change color over time, which helped keep cleaning costs down.

The main entrance on Broadway had a large, rounded arch. The fourth floor had a big cornice, which was at the same height as the roof of the six-story Gilsey Building next door. The building's developer, Robert E. Dowling, hired Vincenzo Alfano to create sculptures for the outside.

The 5th through 25th floors had many windows. Most sections had two or three windows on each floor. Some parts of the building had groups of several stories with decorative columns and balconies. There were also horizontal bands between some of the floors. The 26th floor was hidden inside the cornice.

How Was the Building Built?

The City Investing Building had a strong steel frame with concrete floors. It also used terracotta for floor arches and inside walls, and marble for interior decorations. When finished, the building weighed about 86,000 tons, not including the weight of people and furniture. The steel frame alone weighed 12,000 tons. The building used millions of bricks, thousands of lighting fixtures, and tons of terracotta. It also had miles of plumbing, heating pipes, and electrical wires. The wood inside, like mahogany, was treated to be fireproof.

The building's structure was a steel cage, meaning columns on each floor supported the walls. These columns sat on strong steel bases that spread their weight. There were 89 columns on each floor, arranged in six rows. The largest column held a weight of about 1,719 tons. The floors were made of hollow tile or concrete with cinder filling, topped with mosaic or terrazzo tiles. Large steel beams, some weighing about 105 tons, were used to support the third floor of the Broadway section. Special braces were added to help the building resist strong winds.

The outside walls were "curtain walls," which means they didn't support the building's weight. They were thick at the bottom (32 inches) and got thinner towards the top (12 inches just below the 25th floor).

What About the Foundation?

The building's foundation was dug using large, rectangular boxes called caissons. These boxes were pushed through layers of earth, sand, clay, and water until they reached solid rock, about 80 feet below Broadway. The main digging went 24 feet deep, but for the boiler room, it went 30 feet deep. Each caisson was filled with concrete after the ground was removed from inside it. The foundation's retaining walls were made of concrete slabs between steel I-beams. The digging removed a lot of old building material and earth.

Inside the foundation, there were 59 concrete piers that supported the steel columns of the building above. These piers varied in size. Most of the outside columns were supported by cantilevers, which are beams that stick out from a main support. The cellar floor was a single layer of concrete, 6 feet thick. This helped spread the building's weight and resist the upward push of groundwater.

What Was Inside the Building?

The City Investing Building was one of New York City's biggest office buildings when it was finished, with about 12 acres of floor space. Higher floors generally had more space than lower ones. This was partly because the building's elevators were set up in three groups, each serving different floors. For example, the 5th through 9th floors had about 17,600 square feet each, while the 18th through 25th floors had about 19,500 square feet. The very top floors (27th through 31st) were smaller, with about 5,200 square feet each. There was also a lunch club at the very top of the building.

The main entrance on Broadway led to a limestone entryway about 30 feet deep. This entryway opened into a grand, two-story lobby that stretched all the way to Church Street. The lobby was 40 feet tall and 32 feet wide. Its arched ceiling was decorated with colorful paintings. The entire lobby was covered with different types of beautiful Italian marble. Three groups of elevators were located along the south wall of the lobby. The second floor had offices north of the lobby, and a walkway crossed the lobby to connect the elevators and offices.

On the upper floors, there was usually an elevator hallway along the south wall, with the rest of the space rented out as offices. The ceilings were higher on the lower floors. The first floor had a 22-foot ceiling, and the second floor had a 20-foot ceiling. Most other floors had ceilings between 11 and 14 feet high. The basement, which was at ground level on Church Street, had a 13-foot ceiling, and the cellar had a 24-foot ceiling.

How Did the Building Work?

A large cellar, about 32,000 square feet, extended under the Broadway sidewalk. This area held the building's boiler room, which could produce 2,000 horsepower. The building also had a water system that could filter 864,000 gallons of water per day. There were two water tanks: one for fire protection (12,500 gallons) and another for daily use by tenants (9,000 gallons). The building also had its own electric light plant.

The building had 24 elevators in total. In the lobby, there were 21 passenger elevators and 2 freight elevators. The passenger elevators were divided into three groups:

- Seven elevators served floors 1 to 9.

- Another seven elevators went straight to the 9th floor, then served floors 9 to 17.

- The last seven elevators went straight to the 17th floor, then served floors 17 to 26.

A separate elevator served floors 25 through 32. There were also two staircases from the basement to the 25th floor, and another staircase went up to the 32nd floor.

History of the City Investing Building

The City Investing Building was built by Robert E. Dowling, who was also developing other large buildings nearby at the time. Dowling was the head of the City Investing Company. In early 1906, he hired Francis Kimball, who was known for building large skyscrapers. Dowling wanted the building to have huge floors for companies that needed a lot of office space. He also wanted a grand lobby and many elevators for tenants.

How Was It Built?

The City Investing Company bought the land for the building in January and April 1906. The main construction contract was given to the Hedden Construction Company in September 1906. There were rumors that the building would be 39 stories tall, almost as tall as the Singer Tower being built next door, but this didn't happen. Old buildings on the site were torn down throughout 1906. One building, the Coal and Iron Exchange Building, took five months to demolish because it was so strongly built.

Digging for the foundations started in November 1906. About 275 workers during the day and 100 at night worked on it. The digging had to be finished in 120 days. Workers used temporary wooden platforms and hoisting machines to remove dirt and place the foundation beams. Because there wasn't much space, the contractors' offices were under these temporary platforms. During the digging, the foundations of the nearby Gilsey Building had to be supported because they were not very deep.

After the foundations were done, a light wooden frame was built on the Broadway side to help lift the massive steel beams. Workers put up the beams quickly, sometimes erecting 16 beams and 20 columns in a week. The building was finished in a record 22 months, employing 3,000 workers.

How Was It Used?

Tenants began moving into the building in April 1908. Some early tenants included the Interborough Rapid Transit Company (which ran subways), Midvale Steel, and the American Car and Foundry Company. In December 1919, a banker named Grigori Benenson bought the City Investing Building for $10 million. The building was then renamed the Benenson Building. Benenson received a large loan for the building in 1926.

In the 1920s, companies like Chemical Bank moved into the Benenson Building. Benenson also bought land next door, planning to build an even taller skyscraper. However, these plans were stopped by the Wall Street Crash of 1929. Benenson's company faced financial problems and couldn't pay its loans. In October 1931, the Benenson Building was put up for sale. Charles F. Noyes bought it the next month.

By 1936, there were plans to update the Benenson Building. In 1938, it was sold again to The New York Trust Company for $5 million, and it was renamed 165 Broadway. The building was renovated in 1941 for $300,000. The entrances, elevators, and hallways were updated, and new fluorescent lights were installed. At that time, Chemical Bank used the first six floors of both 165 Broadway and the Gilsey Building. In 1947, 165 Broadway and the Gilsey Building were sold again for $11 million.

Why Was It Torn Down?

In 1964, United States Steel bought the City Investing Building and the neighboring Singer Building. U.S. Steel planned to tear down the entire block to build a new 54-story headquarters. While people tried to save the Singer Building because of its history, the City Investing Building didn't get as much attention. Both buildings were being torn down by 1968.

The new building, called the U.S. Steel Building (later One Liberty Plaza), was finished in 1973. One Liberty Plaza had more than twice the amount of space as the City Investing Building and Singer Building combined. At the time it was torn down, the City Investing Building was the third-tallest building ever voluntarily demolished, after the Morrison Hotel and the Singer Building.

What Was Its Impact?

The City Investing Building, along with other nearby skyscrapers like the Singer Building and Hudson Terminal, was often photographed in Lower Manhattan. When the Equitable Building was completed nearby in 1915, it cast a huge shadow over the City Investing Building, covering it up to the 24th floor. This problem led to New York City's 1916 Zoning Resolution, a new rule that required buildings to be set back from the street above a certain height to allow more light.

Some architectural experts called the City Investing Building a "monument to greed" because of its huge size. Photographs of the building usually showed its north side on Cortlandt Street, because its main side on Broadway was very narrow. The building's architect, Francis Kimball, said the light-colored outside of the building stood out from the "darker" buildings nearby.

See also

In Spanish: City Investing Building para niños

In Spanish: City Investing Building para niños

| Precious Adams |

| Lauren Anderson |

| Janet Collins |