St. Paul Building facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St. Paul Building |

|

|---|---|

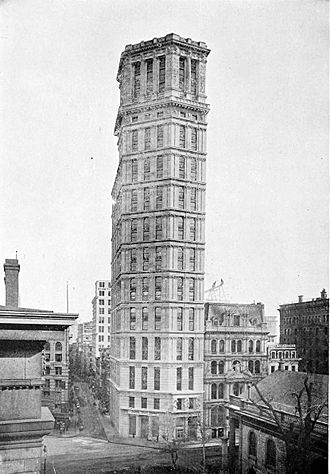

Seen in 1897

|

|

| Etymology | St. Paul's Chapel |

| General information | |

| Status | Demolished |

| Location | 40°42′40″N 74°00′31″W / 40.71111°N 74.00861°W |

| Address | 220 Broadway |

| Town or city | New York City |

| Country | United States |

| Construction started | 1895 |

| Completed | 1898 |

| Demolished | 1958 |

| Cost | $38 million |

| Height | 315 feet (96 m) |

| Technical details | |

| Floor count | 26 |

| Design and construction | |

| Architect | George B. Post |

The St. Paul Building was a famous skyscraper in New York City. It stood in the Financial District of lower Manhattan. Its address was 220 Broadway, at the corner of Ann Street.

George B. Post designed the building. It was finished in 1898. At 26 stories and about 315 feet tall, it was one of the tallest buildings in New York City.

The outside of the building, called the facade, had special features. It included double-height columns in the Ionic style. There were also three sculptures created by Karl Bitter. The building's base was built on sand, not on the deep rock below. This was a unique way to build a tall skyscraper.

The St. Paul Building mostly had offices inside. It had six elevators to help people get to different floors. The Havemeyer family bought the land in 1895. The building got its name from St. Paul's Chapel, which was right across Broadway. The Havemeyer family owned the building until 1943. Then, it was sold to Webb and Knapp and later to Chase Bank.

In 1958, the St. Paul Building was taken down. This made space for the new Western Electric Building. Some parts of its facade, including Karl Bitter's sculptures, are still around. You can see them in Holliday Park in Indianapolis.

Contents

Building Design and Features

The St. Paul Building was 26 stories tall and reached about 315 feet high. It also had two levels underground. George B. Post was the main architect for this project. Robinson and Wallace were the general contractors. J. B. & J.M. Cornell handled the steel work. Karl Bitter designed the sculptures near the building's entrance.

The building stood on a unique five-sided piece of land. It was bordered by Broadway to the west and Ann Street to the north. It was also near Park Row. The building's address was 220 Broadway. It was right across from St. Paul's Chapel.

What the Outside Looked Like

The front and side walls facing Broadway and Ann Street were made of limestone. These walls had three main parts, like a classic column. There was a four-story base, a 16-story middle section (the shaft), and a five-story top part (the capital). The back walls were made of brick and were not decorated.

The first four stories formed the "base" of the building. They had rough-cut stone blocks. There were decorative ledges, called cornices, above the first, second, and fourth floors. On the Broadway side, above the first floor, were three sculptures by Karl Bitter. These sculptures were called "Racial Unity." They showed three stone figures, like atlantes, holding up parts of the building. These figures represented a Black person, a white person, and a Chinese person.

From the 5th to the 20th stories, the facade was divided into eight sections. Each section was two stories tall. There were Ionic-style columns between the windows. These columns supported cornices above every even-numbered floor. The 21st story was a transition floor. It had carved panels between its windows. A larger cornice stuck out above this floor.

The top five stories were the "capital" of the building. The 22nd through 25th floors were easy to see from the street. The 26th floor was hidden by a low wall at the very top. It got light from skylights.

How the Building Stood Strong

The solid rock, called bedrock, under the St. Paul Building was very deep. It was about 86.5 feet down. Above the bedrock was a layer of very fine, compact sand. Instead of digging all the way to the bedrock, the builders stopped at the sand layer. This layer was about 31.5 feet deep.

They tested the sand by putting heavy loads on it. The sand proved to be very stable. Then, they covered the entire area with a 12-inch layer of concrete. This concrete helped spread the building's huge weight evenly. Steel supports were placed on top of the concrete. These supports held up the building's columns and beams. The foundation did not use piles, which are long poles driven into the ground. This was because the sand was already very firm.

The building's outer walls were connected to its inner frame. Strong steel beams were painted three times to protect them. This was done before they were even put into place. The beams underground were covered with asphalt. The floors inside the building were made of tile arches.

Inside the St. Paul Building

The St. Paul Building had a single staircase on its far eastern side. At the western end, there were six elevators. They were arranged in a curve. Two elevators went from the lobby to the 8th floor. Another two went express to the 8th floor, then stopped at floors up to the 16th. The last two went express to the 16th floor, then stopped at all floors up to the 26th.

Offices faced outward from a hallway that ran between the stairs and elevators. There were also offices around the elevator area. Each floor had two small storage rooms. The 26th floor was used for building utilities. It held the building's water tank. The building had a special standpipe system for fire safety. It used very high water pressure.

Building History

Construction and Early Use

Before the St. Paul Building was built, the site held Barnum's American Museum. This museum burned down in 1865. Later, the old headquarters of the New York Herald newspaper stood there. The Herald building was put up for sale in 1894. The Havemeyer family bought it for $950,000 in January 1895. In May of that year, the Herald building was torn down.

The Havemeyer family hired George B. Post to design the new St. Paul Building. Builders tested the ground in early 1896. During construction, in May 1896, a large beam fell from the building. Sadly, it killed a person walking by. The St. Paul Building was finished in 1898. It cost about $1.09 million. When it was completed, it was one of New York City's tallest buildings. Only the Park Row Building, finished in 1899, was taller.

In the early 1900s, famous people and groups had offices in the St. Paul Building. The Outlook magazine was a tenant. Theodore Roosevelt worked there as an associate editor after being U.S. president. The Havemeyers thought about selling the building as early as 1919. But they kept it until April 1943. Then, Webb and Knapp bought it. In August 1943, Chase National Bank bought the St. Paul Building for cash.

Why the Building Was Demolished

In the 1950s, AT&T's Western Electric company grew very large. It needed more space than its headquarters at 195 Broadway. In 1957, Western Electric started planning a new building. They chose the site of the St. Paul Building. By 1959, the St. Paul Building was being torn down. It became the tallest building ever torn down on purpose at that time. Western Electric's new 31-story building, at 222 Broadway, was finished in 1962.

Saving Parts of the Facade

In August 1958, a group called the Committee to Preserve American Art was formed. They wanted to save artworks from buildings that were going to be torn down. They especially wanted to save the St. Paul Building's sculptures. These sculptures were worth a lot of money. The committee offered to pay to remove them.

Many places wanted the sculptures. These included Columbia University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, and the United Nations. The cities of Indianapolis and Rochester, New York also asked for them. Western Electric agreed to save the sculptures because so many people wanted them.

Indianapolis won the sculptures in November 1958. Elmer Taflinger, an artist from Indiana, suggested moving the sculptures to Holliday Park. He also wanted to move part of the St. Paul Building's lower facade. The statues were carefully removed in early 1959. After being stored for two years, they were put in Holliday Park in 1960. They became part of a display called The Ruins.

Over time, the sculptures and facade became worn down. By 1970, Western Electric even regretted giving them away. But in 1973, The Ruins were cleaned up and officially opened. After another period of wear, the St. Paul Building facade was restored again in 2016.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: St. Paul Building para niños

In Spanish: St. Paul Building para niños

| Bessie Coleman |

| Spann Watson |

| Jill E. Brown |

| Sherman W. White |