Claire Lee Chennault facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

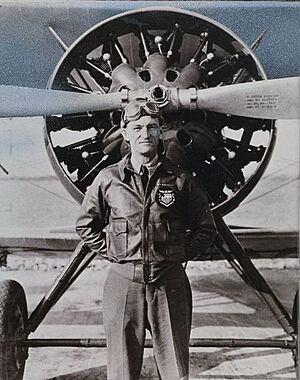

Claire Lee Chennault

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Nickname(s) | "Old Leatherface" |

| Born | September 6, 1890 Commerce, Texas, U.S. |

| Died | July 27, 1958 (aged 67) New Orleans, Louisiana, U.S. |

| Buried | |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

(1945-1958) |

| Years of service | 1917–1945 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held |

|

| Battles/wars |

|

| Awards |

|

| Spouse(s) |

|

Claire Lee Chennault (born September 6, 1890 – died July 27, 1958) was an American military pilot. He is most famous for leading the "Flying Tigers" and the Chinese Air Force during World War II.

Chennault strongly believed in using fighter planes to attack enemy aircraft in the 1930s. At that time, the United States Army Air Corps mostly focused on large bomber planes. Chennault left the U.S. Army in 1937. He then went to China to work as an aviation advisor and trainer.

In early 1941, Chennault took command of the 1st American Volunteer Group. This group was famously known as the Flying Tigers. He led both this volunteer group and the official U.S. Army Air Forces units that took over in 1942. He often disagreed with General Joseph Stilwell, the U.S. Army commander in China. Chennault helped China's leader, Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, convince President Roosevelt to remove Stilwell in 1944. The China-Burma-India theater was a very important area during the war. It helped keep many Japanese soldiers busy in China, stopping them from fighting Allied forces in the Pacific.

Contents

Early Life

Claire Lee Chennault was born in Commerce, Texas. He grew up in the towns of Gilbert and Waterproof, Louisiana. His family pronounced his last name "Shen-awlt."

He attended Louisiana State University for a short time. Later, he worked as a school principal in Louisiana.

Early Military Career

Chennault joined the Army Signal Corps in 1917, during World War I. He learned to fly in the United States Army Air Service. After the war, he continued to serve in the military as a pilot. He became a leader in the "Pursuit Section" at the Air Corps Tactical School in the 1930s. This school taught pilots how to fly fighter planes.

Leading Air Teams

In the mid-1930s, Chennault led an amazing aerobatic team called the "Three Musketeers." They were part of the Army Air Corps. Later, he renamed the team "Three Men on the Flying Trapeze." They performed exciting air shows.

Leaving the Military

Chennault left the military on April 30, 1937. He had some health problems, like deafness and bronchitis. He also had disagreements with his commanders. After leaving the army, he was asked to go to China. There, he would help train Chinese pilots.

In China

Chennault arrived in China in June 1937. He was hired to study the Chinese Air Force. Chiang's wife, Soong Mei-ling, was in charge of aviation. She became Chennault's boss. When the Second Sino-Japanese War began in August, Chennault became Chiang Kai-shek's main air advisor. He helped train new Chinese Air Force pilots. He even flew some scouting missions himself.

He also helped organize a group of foreign pilots called the "International Squadron." These pilots came from different countries to help China.

Creating the Flying Tigers

Chennault's work in Washington, D.C., led to the idea of forming an American Volunteer Group. This group would consist of American pilots and mechanics to help China. The U.S. government agreed to provide money and planes.

The U.S. sent 100 P-40B Tomahawk planes to China. These planes were shipped to Burma in crates. They were put together there and then sent to the training unit. The Flying Tigers had their first battle on December 20, 1941.

Chennault recruited about 300 American pilots and ground crew. They pretended to be tourists. These brave men became a skilled fighting unit. They often fought against larger Japanese forces. They became known as the "Flying Tigers" and were a symbol of American strength in Asia.

Plan to Bomb Japan

Before the U.S. officially joined the war, Chennault had a bold plan. He wanted his Flying Tigers to use U.S. bombers with Chinese markings to attack Japanese bases. He believed a small group of planes could win the war quickly.

The U.S. Army was against this plan. They doubted that Chinese troops could build and protect airfields close enough to Japan. However, U.S. leaders like President Roosevelt liked the idea. But the American attack never happened. The Chinese forces could not secure bases close enough to Japan. The bombers and crews arrived after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor in December 1941. They were then used to fight in Burma instead.

The Flying Tigers in Action

Chennault's 1st American Volunteer Group, the "Flying Tigers," began training in August 1941. They were based in Rangoon, Burma, and Kunming, China. Just weeks after the attack on Pearl Harbor, the Flying Tigers had their first air battle. They shot down four Japanese planes heading to attack Kunming.

This made Claire Chennault famous as an American military leader who struck back at Japan. Even though he was a civilian at the time, he was paid and promoted by Chiang Kai-Shek.

The Flying Tigers fought the Japanese for seven months after Pearl Harbor. They used P-40 planes. Chennault's tactics helped them protect the Burma Road and other important places. He also helped train a new generation of Chinese fighter pilots.

In 1942, the Flying Tigers officially became part of the United States Army Air Forces. Chennault rejoined the Army and quickly rose in rank. He became a major general and commanded the Fourteenth Air Force.

Fighting in China and Burma

During the war, Chennault had many disagreements with the American ground commander, General Joseph Stilwell.

Chennault believed his Fourteenth Air Force could attack Japanese forces from bases in China. He thought this would help the Chinese troops. Stilwell, however, wanted air support to help open a supply route through Burma. This route would bring supplies to a larger Chinese army.

Chiang Kai-shek preferred Chennault's plan. He was careful about starting big attacks against the Japanese. He wanted to save his troops for future conflicts.

Stilwell and Chennault had very different personalities. Stilwell was a strict "Yankee" who valued moral courage. Chennault was a "Southern gentleman" who was more relaxed. They often clashed because of their different ideas on how to fight the war.

In 1944, the Japanese launched a huge attack called Operation Ichigo. Chennault's 14th Air Force fought hard, bombing Japanese supply lines. But the Chinese soldiers were not well-equipped. Chennault wanted to air-drop supplies to them, but Stilwell refused. He thought it would be a waste of effort.

The Japanese captured some of Chennault's air bases. However, the Allied air forces slowly gained control of the skies over Burma. Supplies also began to arrive in China through an airlift called "the Hump." Chennault had always argued for expanding this airlift. The airlift continued to grow and delivered huge amounts of supplies. Chennault retired from the Army Air Forces on October 31, 1945, after Japan surrendered.

Postwar Life

After the war, Chennault returned to China. He bought old military planes and started an airline called the Civil Air Transport (later known as Air America). This airline helped the Chinese Nationalist government. It also supported French forces in Indochina and later helped the US intelligence community.

Chennault believed that the U.S. should continue to support Asian countries fighting against communism. He also thought foreign aid should be given with clear goals and close monitoring.

Memoirs

In 1949, Chennault wrote a book about his life called Way of a Fighter. The book shares his experiences in China. It explains the challenges he faced in using airpower. It also talks about his disagreements with General Joseph Stilwell.

Death

Chennault was diagnosed with cancer in late 1957. He had been a smoker for many years. He and his wife, Anna, traveled to Europe and Taiwan one last time.

He was promoted to the honorary rank of lieutenant general in the U.S. Air Force on July 18, 1958. He died nine days later, on July 27, in New Orleans. He is buried at Arlington National Cemetery.

Personal Life

Chennault was married twice and had ten children. He had eight children with his first wife, Nell Thompson. They were married in 1911 and divorced in 1946. His eldest son, John Chennault, also became a military officer.

He married his second wife, Chen Xiangmei (Anna Chennault), in 1947. She was a young reporter. They had two daughters together. Anna Chennault later became an important lobbyist for the Republic of China (Taiwan) in Washington, D.C.

Legacy

In December 1972, Chennault was honored by being inducted into the National Aviation Hall of Fame. He was also honored with a U.S. postage stamp.

There are statues of Chennault in Taipei, Taiwan, and at the Louisiana State Capitol in Baton Rouge. The Chennault International Airport in Lake Charles is named after him. The Chennault Aviation and Military Museum in Monroe, Louisiana, also honors him.

A vintage Curtiss P-40 aircraft, painted in Flying Tigers colors, is on display in Baton Rouge. In 2006, the University of Louisiana at Monroe renamed its sports teams the "Warhawks," after the P-40 fighter plane. Many of General Chennault's awards are on display at the Smithsonian Air and Space Museum in Washington, D.C.

For a long time, Chennault was not seen positively in the People's Republic of China. But this has changed over time. In 2005, the "Flying Tigers Memorial" was built in China. In 2012, the Kunming Flying Tigers Museum opened. In 2015, the president of Taiwan awarded a medal to Chennault, which his widow accepted.

Film Portrayal

Claire Chennault has been shown in movies. In the 1945 film God Is My Co-Pilot, he was played by Raymond Massey.

Awards and Decorations

Chennault received many awards for his service, including:

- Army Distinguished Service Medal

- Navy Distinguished Service Medal

- Legion of Merit

- Distinguished Flying Cross

- Air Medal

- World War I Victory Medal

- American Defense Service Medal

- American Campaign Medal

- Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal

- World War II Victory Medal

- Order of Blue Sky and White Sun (Republic of China)

- Order of the Cloud and Banner (Republic of China)

- Order of the British Empire (United Kingdom)

- Légion d'honneur (France)

- WWII Croix de Guerre (France)

- Order of the Bath (United Kingdom)

- Order of Polonia Restituta (Poland)

- China War Memorial Medal (Republic of China)

See also

In Spanish: Claire Chennault para niños

In Spanish: Claire Chennault para niños

- Jimmy Doolittle

- Pappy Boyington

- James H. Howard

- John Birch

- History of the Republic of China

- Republic of China Armed Forces

- National Revolutionary Army

- Whampoa Military Academy