Joseph Stilwell facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Joseph Stilwell

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Nickname(s) | "Vinegar Joe", "Uncle Joe" |

| Born | March 19, 1883 Palatka, Florida, US |

| Died | October 12, 1946 (aged 63) San Francisco, California, US |

| Allegiance | United States |

| Service/ |

United States Army |

| Years of service | 1904–1946 |

| Rank | General |

| Service number | 0-1912 |

| Unit | Infantry Branch |

| Commands held | 7th Infantry Division III Corps China Burma India Theater Chinese Expeditionary Force (Burma) Chinese Army in India Northern Combat Area Command Army Ground Forces Tenth United States Army Sixth United States Army Western Defense Command |

| Battles/wars | Philippine–American War

|

| Awards | Distinguished Service Cross Army Distinguished Service Medal (2) Legion of Merit Bronze Star Medal |

| Other work | Chief of Staff to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek |

Joseph Warren "Vinegar Joe" Stilwell (March 19, 1883 – October 12, 1946) was a United States Army general who played a big role in the China Burma India Theater during World War II. He became famous early in the war for leading his troops on a long walk out of Burma when they were being chased by the Japanese army.

Stilwell was known for being very tough. He often pushed his soldiers, even when they were sick, which sometimes made them unhappy. He also had strong disagreements with the Chinese leader, Chiang Kai-shek, especially about how to fight the Japanese and how to use American supplies. Stilwell wanted the Chinese Nationalists and Communists to work together against Japan, as he was told to do.

Some people admired Stilwell, saying he didn't have enough resources for his difficult tasks. Others criticized him, calling him unprofessional, and felt his actions contributed to problems in China.

Contents

Early Life and Education

Joseph Stilwell was born on March 19, 1883, in Palatka, Florida. His parents were Dr. Benjamin Stilwell and Mary A. Peene. Joseph, known as Warren to his family, grew up in Yonkers, New York. His father was very strict, especially about religion.

As a teenager at Yonkers High School, Stilwell was quite rebellious. Before his last year, he had been a great student and played football (as quarterback) and track. But in his final year, he joined a group of friends who got into trouble. After one incident where an administrator was hurt, his friends were expelled. Since Stilwell had already graduated, his father sent him to the US Military Academy at West Point, instead of Yale University as planned.

Stilwell got into West Point even though he missed the application deadline. His family used their connections to reach US President William McKinley. In his first year, he went through a tough initiation process for new students, which he called "hell." At West Point, Stilwell was good at languages, especially French, where he was top of his class in his second year. He also helped bring basketball to the academy and was captain of the cross-country running team. He graduated in 1904, ranking 32nd out of 124 cadets.

In 1910, he married Winifred Alison Smith. They had five children, including Joseph Stilwell Jr., who also became a general and fought in several wars.

Early Military Career

After graduating, Stilwell taught at West Point. He also attended advanced military courses. During World War I, he was an intelligence officer for the Fourth Corps. He helped plan the St. Mihiel Offensive in France. For his excellent service, he received the Army Distinguished Service Medal. The award recognized his hard work in gathering important information about enemy activities, which greatly helped the planning and success of the operations.

Stilwell is often remembered by his nickname, "Vinegar Joe." He got this name while commanding troops at Fort Benning, Georgia. He was known for giving very harsh feedback during training exercises. One soldier, upset by Stilwell's sharp comments, drew a cartoon of Stilwell popping out of a vinegar bottle. Stilwell found the drawing, liked it, and even had it photographed and shared with his friends.

World War II Service

Between World War I and World War II, Stilwell spent three different periods in China. There, he became very good at speaking and writing Chinese. From 1935 to 1939, he was a military expert at the US embassy in Beijing. Later, he helped organize and train the 7th Infantry Division in California. His leadership style, which focused on caring for the average soldier and avoiding unnecessary rules, earned him another nickname: "Uncle Joe."

Before World War II, Stilwell was considered one of the Army's best commanders. He was first chosen to lead the Allied invasion of North Africa. However, he and other US military leaders doubted the plan. They worried about submarine attacks and the risk of Francoist Spain joining the enemy. Stilwell wrote a very critical report about the British. Because of this, his superiors decided to send him elsewhere. When a senior officer was needed in China to keep them fighting the war, President Franklin Roosevelt and General George Marshall chose Stilwell, even though he didn't want to go.

Stilwell became the chief advisor to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, the leader of China. He was also the US commander in the China Burma India Theater (CBI). He was in charge of all Lend-Lease supplies sent to China. Later, he became a deputy commander in the South East Asia Command. Despite his high rank, he often argued with other Allied officers. These arguments were about how to share supplies, Chinese political groups, and whether Chinese and US forces should be under British command.

Fighting in Burma

In February 1942, Stilwell was promoted to lieutenant general and sent to the China-Burma-India Theater (CBI). He had three main jobs there:

- Commander of all US forces in China, Burma, and India.

- Deputy commander of the Burma-India Theater under Admiral Louis Mountbatten.

- Military advisor to Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek, who led all Chinese Nationalist forces.

The CBI was a huge area, but unlike other war zones, it didn't have one main American commander for all operations. Chiang Kai-shek led the Chinese forces, and the British led the Burma-India forces. There were very few American combat troops in the CBI, so Stilwell mostly commanded Chinese soldiers.

The British and Chinese forces were not well-equipped and often struggled against Japanese attacks. Chiang Kai-shek wanted to save his troops and supplies to fight the Japanese later, and also against the Chinese Communists. He became even more careful after seeing how badly the Allies performed during the Japanese invasion of Burma. After fighting Japan for five years, many Chinese felt the Allies should take on more of the fighting.

The Allies had different ideas about how to fight. Chiang preferred a "defense in depth" strategy. Both the British and Americans at first underestimated the Japanese, who were very good at jungle warfare. The Japanese successfully outsmarted the British, used air support, and gained local support.

The situation was made worse by misunderstandings and soldiers not following orders. In one case, a British force left two brigades behind after blowing up a bridge too early. In another, Chinese units didn't follow orders during an ambush.

Stilwell believed the first step to winning was to reform the Chinese Army. However, this plan interfered with the political alliances that kept Chiang in power. Chiang worried that new US-led forces would become independent and outside his control. His staff also didn't want Chinese troops used to help the British regain control of Burma.

Chiang preferred the ideas of Major General Claire Lee Chennault, who thought the war could be fought mostly with Chinese forces supported by air power. This led to a competition between Chennault and Stilwell for valuable supplies flown over the Himalayas from India, a dangerous route known as "The Hump." General George Marshall later said that Stilwell had "one of the most difficult" assignments of any commander.

After the Allied defenses in Burma collapsed, cutting off China from supplies, Stilwell refused an offer for an airlift. Instead, he led his staff of 117 people on foot out of Burma into Assam, India. They marched at a fast pace, which his men called the "Stilwell stride." Two men who were with him, Frank Dorn and Jack Belden, wrote books about this difficult journey. Many other Allied and Chinese forces also used this route to retreat.

Stilwell's walkout meant he was separated from about 100,000 Chinese troops still in Burma. About 25,000 of them died during their retreat due to the harsh jungle, lack of supplies, and Japanese attacks.

In India, Stilwell became known for his direct style and dislike of military show-offs. He often wore a worn-out Army hat, regular GI shoes, and a simple uniform without rank insignia. He usually carried a rifle instead of a pistol. His dangerous march out of Burma and his honest comments about the disaster captured the American public's attention. He famously said, "I claim we got a hell of a beating. We got run out of Burma and it is humiliating as hell. I think we ought to find out what caused it, go back and retake it."

However, Stilwell's negative comments about British forces, which he called "Limey" forces, upset British commanders.

After Japan took over Burma, China was almost completely cut off from Allied help. Supplies could only come through the dangerous "Hump" airlift. Early in the war, the US had prioritized other war zones for troops and equipment. The loss of Burma made it very hard to even replace Chinese soldiers who were lost in battle. This threatened the Allies' plan to keep China fighting Japan by providing air and supply support.

Stilwell believed that Chinese soldiers could be as good as any others with proper training. He set up a training center in Ramgarh, India, for Chinese troops who had retreated from Burma. His efforts faced resistance from the British, who worried that trained Chinese soldiers might inspire Indian rebels. Chiang also resisted, not wanting a strong military unit outside his control.

From the start, Stilwell's main goals were to open a land route to China through northern Burma and to train a strong Chinese army to fight the Japanese. He argued that the CBI was the only place where the Allies could fight a large number of Japanese troops. However, the supply chain over the Hump was still being set up, and supplies were barely enough for air operations and to replace Chinese losses, let alone equip a whole army.

Also, important supplies meant for the CBI were often sent to other war zones. Some supplies that did make it over the Hump were even sold on the black market by Chinese and American personnel. Because of this, most Allied commanders in India focused on defense, except for General Orde Wingate and his Chindits.

Arguments with Chinese and British Leaders

Stilwell left the defeated Chinese troops and escaped Burma in 1942. Chiang had given him command of these troops, but Chinese generals later said they saw Stilwell more as an "adviser" and sometimes took orders directly from Chiang. Chiang was very angry that Stilwell seemed to abandon his best army, the 200th Division, without orders. This made Chiang question Stilwell's abilities.

Chiang was also furious about Stilwell's strict control over US lend-lease supplies to China. When Roosevelt and Marshall asked Chiang about Stilwell's leadership after the Burma disaster, Chiang said he had "full confidence" in Stilwell. But then, he secretly canceled some of Stilwell's orders to Chinese units.

An angry Stilwell started calling Chiang "the little dummy" or "Peanut" in his reports to Washington, DC. "Peanut" was originally a secret code word for Chiang in official messages. Chiang, in turn, often complained to US envoys about Stilwell's "recklessness, insubordination, contempt, and arrogance." He was especially upset by Stilwell's focus on attacking Burma while eastern China was falling to Japan.

Stilwell was also very frustrated by the widespread corruption in Chiang's government. He kept a diary where he noted the corruption and how much money was being wasted. For example, it's estimated that 60-70% of Chiang's new soldiers didn't finish basic training; many deserted or died of starvation. Stilwell eventually believed that Chiang and his generals were so bad that he wanted to stop all US aid to China.

Stilwell pushed Chiang and the British to retake Burma. But Chiang demanded huge amounts of supplies before he would attack. The British refused to send troops, partly because of Churchill's "Europe first" strategy, which focused on defeating Germany first.

Stilwell often complained to Roosevelt that Chiang was saving US supplies to fight Mao Zedong's Communists after the war with Japan. However, from 1942 to 1944, most US military aid over the Hump went to the 14th Air Force and US personnel in China.

Stilwell also argued with Field Marshal Archibald Wavell. Stilwell believed the British in India cared more about protecting their colonies than helping China fight Japan. In August 1943, due to constant arguments and different goals among the British, American, and Chinese commands, the CBI command was split into separate Chinese and Southeast Asia Theaters.

Stilwell also opposed Mountbatten's plan in January 1944 for a sea attack in the Bay of Bengal. He wrote in his diary that the British were "welshing" (backing out) and that the plan was full of "fancy charts, false figures and dirty intentions."

Leading the Chindits

During his time in India, Stilwell became more and more unhappy with British forces. He openly criticized what he saw as their hesitant behavior. He was given command of the Chindits, a special British force. Most of their casualties happened while they were under his command. The British saw things differently, pointing out their heavy losses in taking Mogaung without heavy weapons.

Stilwell angered the British by announcing on the BBC that Chinese troops had captured Mogaung, without mentioning the British. The Chindits were furious. Their commander, Michael Calvert, famously sent a message to Stilwell's headquarters saying, "Chinese reported taking Mogaung. My Brigade now taking umbrage." Stilwell's son, an intelligence officer, joked that "Umbrage" was so small he couldn't find it on the map.

Stilwell wanted the Chindits to join the siege of Myitkyina. But Calvert was so sick of the demands on his tired troops that he turned off his radios and went back to Stilwell's base. A military trial seemed likely until Stilwell and Calvert met. Stilwell finally understood the terrible conditions the Chindits had been fighting in. He apologized, blaming his staff for not giving him correct information, and allowed Calvert and his men to withdraw. He told Calvert, "You and your boys have done a great job. I congratulate you," and awarded them medals.

Another Chindit brigade, the 111th, captured a hill called Point 2171. But the men were completely exhausted, suffering from malaria, dysentery, and malnutrition. Doctors examined them, and out of 2200 men, only 119 were fit to fight. The brigade had to be evacuated.

Captain Charlton Ogburn, a US Army Marauder officer, and Chindit commanders John Masters and Michael Calvert later remembered Stilwell sending a staff officer to criticize their troops as being "yellow." In October 1943, when a plan by Stilwell to fly Chinese troops to northern Burma was rejected, Field Marshal Archibald Wavell asked Stilwell if he agreed that the plan wouldn't work for military reasons. Stilwell said yes. Wavell then asked what Stilwell would tell Chiang, and Stilwell replied, "I shall tell him the bloody British wouldn't fight."

Myitkyina Offensive

- Further information: Siege of Myitkyina

In August 1943, Stilwell became deputy supreme Allied commander under Mountbatten. He took command of various Chinese and Allied forces, including a new US special operations unit called Merrill's Marauders. Stilwell prepared his Chinese forces for an attack in northern Burma. On December 21, 1943, Stilwell took direct control of planning the invasion of northern Burma, which aimed to capture the Japanese-held town of Myitkyina. He ordered General Frank Merrill and the Marauders to go on long jungle missions behind Japanese lines, similar to the British Chindits. In February 1944, three Marauder battalions marched into Burma.

In April 1944, Stilwell launched his final attack to capture Myitkyina. The Marauders were ordered to make a difficult 65-mile jungle march to flank the town. They had been fighting since February and were very tired, with many losses from combat and disease. A severe outbreak of amoebic dysentery hit them after they met up with the Chinese Army.

The Marauders began to doubt Stilwell's concern for them. He seemed uncaring about their losses and refused requests for medals for their bravery. Promises of rest were ignored, and they didn't even get new uniforms or mail until late April.

On May 17, the 1,310 remaining Marauders attacked Myitkyina airfield with Chinese troops. They quickly took the airfield. However, the town itself, which Stilwell's staff thought was lightly defended, had many well-equipped Japanese soldiers who were getting more reinforcements. An early attack on the town by Chinese regiments failed with heavy losses. The Marauders didn't have enough men to take Myitkyina quickly. When more Chinese forces arrived, the Japanese had about 4,600 determined defenders.

During the siege, which happened during the rainy season, the Marauders' commanders and doctors urgently recommended that the unit be pulled out for rest. Most of the men had fevers and constant dysentery, making it hard to fight. Stilwell refused to evacuate them. He ordered all medical staff to keep sick soldiers in combat by using medicine to lower fevers. He also ordered special medical "exams" for Marauders evacuated for wounds or illness. These exams often declared sick soldiers fit for duty, and Stilwell's staff looked for any Marauder with a temperature below 103 degrees Fahrenheit. Some men sent back to combat were immediately evacuated again by other doctors. Later, Stilwell's staff blamed the medical personnel for being too strict.

The Japanese fought fiercely, often to the last man. Myitkyina didn't fall until August 4, 1944, after Stilwell had to send in thousands of Chinese reinforcements. Stilwell was happy the town was taken. He later blamed the British and Gurkha Chindits for not helping faster, but the Chindits had also suffered huge losses from battles and illness. Stilwell also hadn't kept his British allies fully informed of his plans.

With no more replacements for his Marauder battalions, Stilwell felt he had to keep pushing them until they reached their goals or were wiped out. He worried that pulling out the Marauders, the only US ground unit, would make it seem like he was playing favorites and force him to evacuate the exhausted Chinese and British Chindits too. When General William Slim suggested withdrawing his men, Stilwell refused. He believed his commanders didn't understand how soldiers sometimes exaggerated physical challenges. Having made his own tough march out of Burma, Stilwell found it hard to sympathize with those who had been fighting in the jungle for months. Looking back, his actions showed he didn't fully understand the limits of lightly-equipped special forces used in regular battles.

The Myitkyina siege and the arguments over evacuation led to an investigation and hearings, but Stilwell faced no punishment for his decisions.

Just a week after Myitkyina fell, the 5307th Marauder force, with only 130 combat-ready men left out of 2,997, was disbanded.

Disagreements with Chennault

One of the biggest arguments during the war was between General Stilwell and General Claire Chennault, who led the famous "Flying Tigers" and later the air force. Chennault suggested a limited air attack against the Japanese in China in 1943, using forward air bases. Stilwell argued that this wouldn't work and that any air campaign should wait until strong air bases with large ground forces were built. Stilwell wanted all air resources to go to his forces in India for an early attack on northern Burma.

Chiang followed Chennault's advice and rejected Stilwell's plan. British commanders also sided with Chennault, knowing they couldn't launch a big Allied attack into Burma in 1943 with the available resources. In mid-1943, Stilwell's headquarters focused on plans to rebuild the Chinese Army for an attack in northern Burma, even though Chiang wanted support for Chennault's air operations.

Stilwell believed that after opening a supply route through northern Burma, he could train and equip 30 Chinese divisions with modern gear. A smaller number of Chinese forces would move to India, where two or three new Chinese divisions would also be formed. This plan remained theoretical because the limited airlift capacity over the Hump was used for Chennault's air operations, not for equipping Chinese ground units.

In 1944, the Japanese launched a counterattack called Operation Ichi-Go. They quickly took over Chennault's forward air bases, proving Stilwell right. By then, the Hump airlift was delivering more supplies each month. With more equipment and troops, and worried about defending India, British authorities now sided with Stilwell.

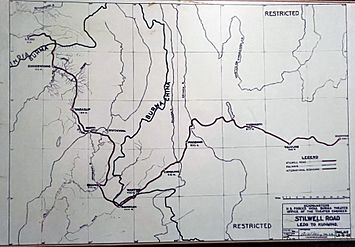

Working with a Chinese Nationalist attack in the south, Allied troops under Stilwell's command launched the long-awaited invasion of northern Burma. After heavy fighting, both forces met up in January 1945. Stilwell's strategy was still the same: opening a new land supply route from India to China would allow the Allies to equip and train new Chinese army divisions to fight the Japanese. This new road, later called the Ledo Road, would connect to the old Burma Road as the main supply route to China. Stilwell's planners thought the route could supply 65,000 tons of supplies per month.

Using these figures, Stilwell argued that the Ledo Road would carry much more tonnage than the Hump airlift. Chennault doubted that such a long road through difficult jungle could ever match the tonnage delivered by modern cargo planes. Progress on the Ledo Road was slow and wasn't finished until January 1945.

In the end, Stilwell's plans to train and modernize 30 Chinese divisions in China and a few in India were never fully completed. As Chennault predicted, the supplies carried over the Ledo Road never reached the levels airlifted monthly into China by the Hump. In July 1945, 71,000 tons of supplies were flown over the Hump, compared to 6,000 tons using the Ledo Road. The airlift continued until the end of the war.

However, when supplies did flow in large amounts over the Ledo Road, it helped the war against Japan. Stilwell's push into northern Burma allowed Air Transport Command to fly supplies into China faster and safer. American planes could fly a more southerly route without fear of Japanese fighters. This increased supply deliveries from 18,000 tons in June 1944 to 39,000 tons in November 1944. On August 1, 1945, planes crossed the Hump every minute and twelve seconds.

In recognition of Stilwell's efforts, Chiang Kai-shek later renamed the Ledo Road the Stilwell Road.

Recall from China

When the China front quickly worsened after the Japanese launched Operation Ichi-Go in 1944, Stilwell saw it as a chance to gain full command of all Chinese armed forces. Operation Ichi-Go was the largest Japanese attack of World War II, meant to defeat China completely. It involved half a million men and 800 tanks. Stilwell argued with Chiang over the city of Guilin, which was under siege by the Japanese. Chiang wanted Guilin defended to the last man, but Stilwell said it was a lost cause.

In his diary, Stilwell wrote that the Chinese leaders should be removed. Stilwell ordered American troops to leave Guilin and convinced a reluctant Chiang to accept the city's loss. This argument over Guilin was followed by another clash. Chiang demanded that his Y Force return from Burma to defend Kunming, the capital of Yunnan Province, which was also threatened by the Japanese.

Stilwell asked Roosevelt directly for help with his dispute with Chiang. Roosevelt sent Chiang a strong message, saying he had urged him many times to take action against the disaster. Roosevelt threatened to end all American aid unless Chiang "at once" placed Stilwell "in unrestricted command of all your forces."

Chennault later claimed that Stilwell had deliberately ordered forces out of Guilin to create a crisis. This crisis, Chennault said, would force Chiang to give up command of his armies to Stilwell. Stilwell's diary entries supported this, as he wrote that a crisis "just sufficient to get rid of the Peanut without entirely wrecking the ship, it would be worth it." Stilwell believed the entire Nationalist system needed to be "torn to bits" and that Chiang had to go.

An excited Stilwell immediately delivered Roosevelt's letter to Chiang. This was despite pleas from Patrick J. Hurley, Roosevelt's special envoy, to delay the message and work out a deal that would be more acceptable to Chiang.

Chiang saw this as an attempt to completely control China. He formally replied that Stilwell must be replaced immediately and that he would welcome any other qualified US general.

Chiang called Roosevelt's letter the "greatest humiliation I have been subjected to in my life." He said it was "all too obvious that the United States intends to intervene in China's internal affairs." Chiang told Hurley that the Chinese people were "tired of the insults which Stilwell has seen fit to heap upon them." Chiang also gave a speech, which was leaked to the press, calling Roosevelt's letter a form of imperialism. He said accepting Roosevelt's demands would make him no different from the Japanese collaborator Wang Jingwei.

On October 12, 1944, Hurley reported to Washington that Stilwell was a "fine man, but was incapable of understanding or co-operating with Chiang Kai-shek." Hurley added that if Stilwell stayed, all of China might be lost to the Japanese. Hurley showed this message to Stilwell before sending it.

On October 19, 1944, Stilwell, who had been promoted to four-star general on August 1, 1944, was called back from his command by Roosevelt. Because of the controversy over casualties in Burma and his ongoing difficulties with British and Chinese commanders, Stilwell's return to the US was not celebrated. He was met by two generals at the airport who told him not to answer any media questions about China.

Stilwell was replaced by General Albert C. Wedemeyer. Wedemeyer later said he dreaded the assignment because serving in the China Theater was considered a "graveyard" for American officials.

When Wedemeyer arrived at Stilwell's headquarters, he was upset to find that Stilwell had left without seeing him and had not left any briefing papers. Most commanders brief their replacements thoroughly. Wedemeyer couldn't find any written records of Stilwell's plans or operations. Stilwell's staff told Wedemeyer that Stilwell kept everything "in his hip pocket."

Despite questions from the news media, Stilwell never complained about how he was treated by Washington or Chiang.

Later Military Career

After a three-month break, Stilwell took command of the Army Ground Forces on January 24, 1945. His headquarters was at the Pentagon. In this role, he oversaw all military training and mobilization of ground units in the United States.

On June 23, 1945, after the death of Lieutenant General Simon B. Buckner, Jr., Stilwell was appointed commander of the Tenth United States Army. This happened shortly after the end of Japanese resistance in the Battle of Okinawa. The Tenth Army was planned to take part in Operation Olympic, the invasion of Honshu, the largest Japanese home island. However, the Tenth Army was disbanded on October 15, 1945, after Japan surrendered.

Post-War Life and Death

In November 1945, Stilwell was asked to lead a "War Department Equipment Board." This board investigated how the Army could modernize based on its recent war experiences. He recommended creating a combined arms force to test new weapons and develop ways to use them. He also suggested getting rid of specialized anti-tank units. His most important recommendation was to greatly improve the army's defenses against all airborne threats, including ballistic missiles. He specifically called for "guided interceptor missiles, dispatched in accordance with electronically computed data obtained from radar detection stations."

On March 1, 1946, Stilwell took command of the Sixth US Army, based at the Presidio of San Francisco. This command managed army units in the Western United States. In May 1946, Stilwell and his former subordinate Frank Merrill helped suppress a prison uprising, known as the Battle of Alcatraz.

Stilwell died after surgery for stomach cancer on October 12, 1946, at the Presidio of San Francisco. He was still on active duty, just five months shy of the Army's mandatory retirement age of 64. His body was cremated, and his ashes were scattered on the Pacific Ocean. A memorial stone was placed at the West Point Cemetery. He received many military awards, including the Distinguished Service Cross and the Combat Infantryman Badge, which was given to him as he was dying.

Personal Views

Historian Barbara W. Tuchman noted that Stilwell was a lifelong Republican. He often shared the strong anti-Roosevelt feelings common among Republicans at the time. However, a close friend described Stilwell as naturally "liberal and sympathetic" but "conservative in thought and politics."

Tuchman also mentioned that Stilwell used some words in his letters and diaries that are now considered insulting, but he seemed to use them without meaning to be offensive.

During World War II, he praised the Soviet military, saying that "the Russian troops appeared to advantage, and those who believe the Red Army is rotten would do well to reconsider their views."

Stilwell also spoke out against racism towards Japanese-American servicemen after the war. He attended rallies and personally presented a medal to the family of a Japanese-American soldier, Kazuo Masuda. At an event in Santa Ana, California, Stilwell praised Japanese-American soldiers, saying, "Who after all is the real American? The real American is the man who calls it a fair exchange to lay down his life in order that American ideals may go on living. And judging by such a test, Sgt. Masuda was a better American than any of us today."

Legacy and Impact

Stilwell was a member of the Scottish Rite of Freemasonry.

In her book Stilwell and the American Experience in China, 1911-45, Barbara Tuchman wrote that Stilwell was removed from his command because he couldn't get along with his allies. Some historians believe President Roosevelt was worried that Chiang would make a separate peace with Japan, which would free up Japanese divisions to fight elsewhere. The power struggles between Stilwell, Chennault, and Chiang reflected political divisions within the US at the time.

Another view suggests that Stilwell, pushing for full command of Chinese forces, had made connections with Mao Zedong's Communist forces. Stilwell bypassed Chiang and got Mao to agree to follow an American commander. Stilwell's aggressive approach in his power struggle with Chiang ultimately led to Chiang demanding his recall.

According to Guan Zhong, a Chinese official, Stilwell once expressed regret that he never had the chance to fight alongside the Chinese Communists, especially with General Zhu De, before his death.

Although Stilwell was seen as a "soldier's soldier," he was an old-school infantry officer. He didn't fully appreciate new developments in warfare during World War II, like strategic air power or using highly-trained infantry as jungle guerrilla fighters. He often disagreed with General Chennault, who Stilwell felt overestimated the power of air attacks against large ground forces. This was shown when the 14th Air Force bases in eastern China fell during the Japanese offensive in 1944.

Stilwell also clashed with other officers, including Orde Wingate (who led the Chindits) and Colonel Charles Hunter (who led Merrill's Marauders). Stilwell didn't understand how much constant jungle warfare affected even the best troops. He also didn't grasp that lightly-armed guerrilla forces couldn't easily defeat heavily-armed regular infantry with artillery support. Because of this, Stilwell was very hard on both the Chindits and Marauders, earning their disapproval.

However, Stilwell was a skilled tactician in traditional land warfare. He deeply understood the logistics needed for fighting in tough terrain. This led to his dedication to the Ledo Road project, for which he received several awards, including the Distinguished Service Cross. The trust Stilwell placed in experts on China, like John Stewart Service and John Paton Davies, Jr., supports this assessment.

Some argue that if Stilwell had been given the number of American infantry divisions he requested, the US experience in China and Burma might have been very different. His Army peers, General Douglas MacArthur and General George Marshall, highly respected his abilities. They both ensured he replaced General Simon Bolivar Buckner, Jr. as commander of the Tenth US Army at Okinawa after Buckner's death. However, in the last year of the war, the US was stretched thin trying to meet all its military needs. Cargo aircraft sent to supply Stilwell and the 14th Air Force in China meant that air-dependent campaigns in the West, like Operation Market Garden, were short of planes.

Even though Chiang succeeded in removing Stilwell, the public image of Chiang's government was badly damaged. Just before Stilwell left, a war correspondent named Brooks Atkinson interviewed him in Chongqing. Atkinson wrote that Stilwell's removal showed the political victory of a "dying, anti-democratic regime" that cared more about staying in power than fighting Japan. Atkinson, who had visited Mao in Yan'an, saw the Communist forces as a democratic movement. His article about Mao was titled Yenan: A Chinese Wonderland City. The Nationalists, in contrast, were seen as hopelessly old-fashioned and corrupt by many US journalists in China. This negative image of the Nationalists in the US played a big role in President Harry Truman's decision to end all aid to Chiang during the Chinese Civil War.

The British historian Andrew Roberts noted Stilwell's negative comments about the British war effort in Asia. This showed his strong dislike for the British, which made cooperation between American and British forces difficult. The British historian Rana Mitter argued that Stilwell never understood that his role as Chiang's chief of staff didn't give him as much authority as Marshall had as US Army chief of staff. Chiang, not Stilwell, was the commander-in-chief of Chinese forces. Chiang resisted Stilwell's plans if they involved risking Chinese forces in battle or moving them out of his direct control to bases in India. Mitter believed Chiang was right to save China's resources after the heavy losses from 1937 to 1941. Mitter also supported the idea that Chennault could have achieved much more if Stilwell hadn't diverted a large portion of lend-lease equipment to Chinese troops in India. Stilwell's mastery of Chinese made him the natural American choice for the China command. Mitter suggested his talents might have been better used in North Africa, as Marshall had originally planned.

The General Joseph Stilwell House was built between 1933 and 1934 in Carmel Point, California. This large, two-story house is still a private home. A stone plaque has been placed on the side of the house to honor him.

Many streets, buildings, and areas across the country have been named after Stilwell. These include Joseph Stilwell Middle School in Jacksonville, Florida. He envisioned a Soldiers' Club in 1940, which was completed in 1943 at Fort Ord. Years later, this building was renamed Stilwell Hall in his honor. However, due to erosion, the building was taken down in 2003. Stilwell's former home in Chongqing, China, has been turned into the General Joseph W. Stilwell Museum to honor him.

Awards and Decorations

Distinguished Service Cross

Distinguished Service Cross Army Distinguished Service Medal with oak leaf cluster

Army Distinguished Service Medal with oak leaf cluster Legion of Merit

Legion of Merit Bronze Star Medal

Bronze Star Medal Philippine Campaign Medal

Philippine Campaign Medal Mexican Border Service Medal

Mexican Border Service Medal World War I Victory Medal

World War I Victory Medal American Defense Service Medal

American Defense Service Medal Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three campaign stars

Asiatic-Pacific Campaign Medal with three campaign stars World War II Victory Medal

World War II Victory Medal Army of Occupation Medal with "ASIA" clasp (awarded after his death)

Army of Occupation Medal with "ASIA" clasp (awarded after his death) Chevalier Légion d'honneur (France)

Chevalier Légion d'honneur (France) Panamanian La Solidaridad Medal 1919

Panamanian La Solidaridad Medal 1919 Nationalist China's Order of Blue Sky and White Sun (offered twice, but he refused it both times)

Nationalist China's Order of Blue Sky and White Sun (offered twice, but he refused it both times) Combat Infantryman Badge (General Stilwell is one of only three general officers to receive this award, which is usually for colonels or lower ranks. The others are Major General William Dean and General Matthew Ridgway. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur received an honorary one.)

Combat Infantryman Badge (General Stilwell is one of only three general officers to receive this award, which is usually for colonels or lower ranks. The others are Major General William Dean and General Matthew Ridgway. General of the Army Douglas MacArthur received an honorary one.)

Dates of Rank

| No pin insignia in 1904 | Second Lieutenant, Regular Army: June 15, 1904 |

| First Lieutenant, Regular Army: March 3, 1911 | |

| Captain, Regular Army: July 1, 1916 | |

| Major, National Army: August 5, 1917 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel, National Army: August 26, 1918 | |

| Colonel, National Army: May 6, 1919 | |

| Captain, Regular Army: September 14, 1919 (returned to permanent rank after World War I) |

|

| Major, Regular Army: July 1, 1920 | |

| Lieutenant Colonel, Regular Army: May 6, 1928 | |

| Colonel, Regular Army: August 1, 1935 | |

| Brigadier General, Regular Army: July 1, 1939 | |

| Major General, Army of the United States: October 1, 1940 | |

| Lieutenant General, Army of the United States: February 25, 1942 | |

| Major general, Regular Army: September 1, 1943 | |

| General, Army of the United States: August 7, 1944 |

See also

In Spanish: Joseph Stilwell para niños

In Spanish: Joseph Stilwell para niños

- Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945)

- Whampoa Military Academy

- History of the Republic of China

- Military of the Republic of China

- Y Force

- Charles N. Hunter

| Mary Eliza Mahoney |

| Susie King Taylor |

| Ida Gray |

| Eliza Ann Grier |