The Hump facts for kids

Quick facts for kids The Hump駝峰航線 |

|

|---|---|

| Part of the Burma Campaign of World War II | |

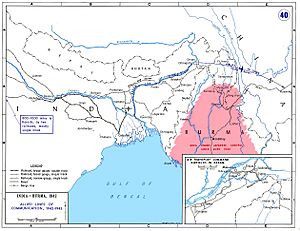

Allied lines of communication in Southeast Asia (1942–43). The Hump airlift is shown at upper right.

|

|

| Location | Assam, India, to Kunming, China |

| Planned | November 1941 |

| Planned by | Republic of China Air Force, United States Army Air Forces, Royal Air Force, ABDA Command |

| Objective | Resupplying the Chinese war effort |

| Date | April 8, 1942 – November 1945 |

| Executed by | Tenth Air Force, India-China Division, XX Bomber Command |

| Outcome | Allied operation successful |

| Casualties |

|

The Hump (Chinese: 駝峰航線) was the name given by Allied pilots during World War II. It referred to the eastern part of the Himalayan Mountains. Pilots flew military transport aircraft over these mountains from India to China. Their mission was to deliver supplies to the Chinese army and the United States Army Air Forces (USAAF) units in China.

In 1942, creating this airlift was a huge challenge for the USAAF. They had no units trained for moving cargo. Also, there were no airfields in the China Burma India Theater (CBI) for the many transport planes needed. Flying over the Himalayas was very dangerous. Pilots faced a lack of good maps, no radio navigation help, and little information about the weather.

The job first went to the USAAF's Tenth Air Force. Later, it was given to its Air Transport Command (ATC). Since the USAAF had no experience with airlifts, they chose commanders who had helped start the ATC. These leaders included former civilians who had run large airlines.

This operation, first called the "India–China Ferry," started in April 1942. This was after the Japanese army blocked the Burma Road, which was the main supply route. The airlift continued daily until August 1945. Most of the people and planes came from the USAAF. British, Indian, and other Commonwealth forces also helped. The Chinese National Aviation Corporation (CNAC) also played a big role. The last flights happened in November 1945, bringing personnel back from China.

The India–China airlift delivered about 650,000 tons of supplies to China. This came at a great cost in lives and aircraft over 42 months. For their brave efforts, the India–China Wing of the ATC received the Presidential Unit Citation in January 1944. This was the first time a non-combat group received such an award.

Contents

Why Was The Hump Needed?

Keeping China in the war was very important for the Allies. It kept over a million Japanese soldiers busy in China. This meant those soldiers couldn't attack other Allied areas in the Pacific. When Japan invaded French Indochina, all sea and rail routes to China were cut off. The only way left was through the Soviet Union. But this route also closed in April 1941. So, the Burma Road became the only land route for supplies.

When Japan quickly took over parts of Southeast Asia, this last supply line was in danger. People started talking about an air route from India as early as January 1942. A Chinese official thought that 12,000 tons of supplies could be flown in each month if 100 C-47 Skytrain planes were used. Chinese Air Force Major General Mao Bangchu was put in charge of finding safe air routes over the Himalayas in 1941. A pilot from CNAC, Xia Pu, made the first flight from Dinjan, India, to Kunming, China, in November 1941. This became the route known as "The Hump."

In February 1942, President Roosevelt said it was "extremely urgent" to keep the path to China open. He sent ten C-53 Skytrooper planes to CNAC to help them grow. When the new Tenth Air Force opened in New Delhi in March 1942, it was given the job of setting up an "India-China Ferry." This would use both U.S. and Chinese planes.

The air route was planned with two main parts. One was from India's western ports to Calcutta, where goods would go by train to Assam. The second part, the "Assam-Burma-China Command," was the route from Assam bases to southern China. The original idea was for the Allies to hold northern Burma and use Myitkyina as a drop-off point. Supplies would then go by river to Bhamo and onto the Burma Road. However, on May 8, 1942, the Japanese took Myitkyina. This, along with losing Rangoon, cut off the Burma Road. To keep supplies flowing to China, U.S. and Allied leaders agreed to start a continuous air supply effort directly between Assam and Kunming.

Airlift Operations Begin

Early Challenges (1942)

The Tenth Air Force faced many problems. Planes and people were often sent to Egypt to help fight Nazi Germany. Its Air Service Command was still on ships from the United States. This meant they had to find planes and crews for the India-China Ferry from anywhere they could. Ten DC-3 planes and crews from Pan American World Airways were sent. Also, 25 other DC-3s from American Airlines in the U.S. couldn't be moved to India because there were no crews.

The way the India-China Ferry was managed was messy. Senior officers in India and Burma argued over who was in charge. On April 23, 1942, Colonel Caleb V. Haynes was put in command of the Assam-Kunming part of the ferry. This was called the Assam-Burma-China Ferry Command. Haynes was a good choice because he had helped start the Air Corps Ferrying Command in 1941. This group had pioneered military air transport overseas.

The first flight "over the hump" happened on April 8, 1942. From the Royal Air Force airfield at Dinjan, Lieutenant Colonel William D. Old used two former Pan Am DC-3s. They carried 8,000 gallons of aviation fuel for the Doolittle Raiders. In May 1942, Allied forces in northern Burma collapsed. This meant the small air effort had to be used for other things. The ABC Ferry Command helped General Stilwell's army retreat and evacuated wounded soldiers. They also started a regular air service to China. They used ten borrowed DC-3s, three USAAF C-47s, and 13 CNAC C-53s and C-39s. Only two-thirds of these planes were ready to fly at any time.

Dinjan was close enough for Japanese fighters from Myitkyina to reach. This forced crews to work on planes all night and take off before dawn. The danger of attack also made the ABC Ferry Command fly a difficult 500-mile route to China. This route went over the Eastern Himalayan Uplift, which became known as the "high hump."

The official history of the Army Air Forces described the route: "The Brahmaputra valley floor is 90 feet above sea level at Chabua. From here, the mountains quickly rise to 10,000 feet and higher. Flying east, pilots first went over the Patkai Range. Then they passed over the upper Chindwin River valley, with a 14,000-foot ridge, the Kumon Mountains, to the east. They then crossed many 14,000- to 16,000-foot ridges. These were separated by the valleys of the West Irrawaddy, East Irrawaddy, Salween, and Mekong Rivers. The main 'Hump,' which gave its name to the whole mountain range and the air route, was the Santsung Range. This range was often 15,000 feet high, between the Salween and Mekong Rivers. East of the Mekong, the land became less rugged. The elevations were more moderate as one got closer to the Kunming airfield, which was 6,200 feet above sea level."

Problems with the Indian railway system meant planes often carried cargo all the way from Karachi to China. Much cargo took as long to reach Assam from Karachi as the two-month journey by ship from the United States. India's roads and rivers were not developed enough to support the mission. Air transport was the only practical way to supply China quickly.

In the first two months, the USAAF delivered only 700 tons of cargo. CNAC delivered 112 tons. Tonnage dropped in June and July because of the summer monsoon. In July, CNAC greatly increased its tonnage to 221 tons. But the 10th Air Force C-47s brought only 85 tons of supplies and people into China.

New Leadership and Challenges (1942-1943)

On June 17, 1942, Colonel Haynes moved to China to command bombers. Colonel Robert F. Tate took his place, but he was also in charge of the Trans-India Command in Karachi. So, Lieutenant Colonel Julian M. Joplin mostly led the India-China operations until August 18. Tate took full command on August 25. On July 15, 1942, the two parts of the India-China Ferry joined to form the India-China Ferry Command.

Tate faced immediate problems. The best pilots and 12 planes were sent to Egypt in June. The airlift grew very slowly during the summer monsoon. Planes were used too much, maintenance was poor, and spare parts were missing. This led to many planes being grounded. There was a particular lack of replacement tires and spare engines.

Three new bases were built by the British on tea plantations at Chabua, Mohanbari, and Sookerating. They were ready in August 1942. But none were expected to be ready for all-weather flights before November or December. This was due to problems with local workers and heavy equipment not arriving from the U.S. Dinjan remained the main transport base during the monsoon.

The poor results of the India-China Ferry led to a suggestion in Washington. They thought about giving control of the operation to CNAC. This would put U.S. military people under foreign civilian control in a combat area. General Stilwell strongly opposed this plan and succeeded. He also made CNAC lease its C-53s and crews to the USAAF. This was to make sure they carried only essential military cargo, not commercial goods. The airlift lost its first plane in an accident on September 23, 1942, likely from ice. After this, plane losses increased sharply.

Protecting the air supply line became the main job of the Tenth Air Force. When the summer monsoon ended, the Japanese were expected to try and cut off the last link to China. The 10th Air Force's China Air Task Force (CATF) was good at defending the eastern end. But little had been done to protect the four Assam airfields from air attacks.

The Japanese air attack happened late on October 25. 100 bombers and fighters surprised the bases. They bombed from 10,000 feet and shot at planes from 100 feet. The only defense came from three P-40s already flying patrol. Six others took off to chase the attackers. Dinjan and Chabua were heavily bombed. Nine transport planes and twenty fighters were destroyed or badly damaged. The next day, Sookerating was attacked by 30 fighters, again without warning. Damage was limited to one storage building. A third raid hit Chabua on October 28 but missed the airfield. The Japanese raids did not happen again in 1942.

Improving the Airlift (1943-1944)

In October 1942, the USAAF looked at the airlift. They felt the commanders of the Tenth Air Force were "defeatist" about the operation. Living conditions for crews and support staff were very bad. This led to low morale.

On October 13, the Air Transport Command offered to take over the operation. They were told to do so by December 1, 1942. They created the India-China Wing ATC (ICWATC), led by Colonel Edward H. Alexander. This new group reported directly to ATC headquarters in Washington, D.C. This ended the divided leadership that had caused problems. The 1st Ferrying Group became the 1st Transport Group. Its 76 C-47s were joined by three Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express planes in January 1943. These were based on the B-24 Liberator bomber.

The first of thirty Curtiss C-46 Commando planes arrived in India in April 1943. The C-46 was a new cargo plane. It could carry much more cargo and fly higher than the C-47. In May, the 22nd Ferrying Group started flying C-46s from the new base at Jorhat. This base had a concrete runway.

However, there was a severe shortage of crews. July's cargo tonnage was less than half of its goal. The airfields were not finished. Most new pilots were only trained for single-engine planes. Specialized maintenance staff and equipment were sent by ship, which took a long time. The new C-46 also had its own problems. Intense heat and heavy monsoon rains made things even harder.

In September 1943, another team inspected the operation. This team was led by ATC commander Major General Harold L. George. He brought Colonel Thomas O. Hardin, a former airline executive. On September 16, Hardin was put in charge of the Eastern Sector of the ICW to boost operations. Alexander was replaced by Brigadier General Earl S. Hoag on October 15. George also started the "Fireball," a weekly C-87 flight carrying critical spare parts from Ohio to India.

Japanese fighters in central Burma started attacking the transport route. On October 13, 1943, many fighters shot down a C-46, a C-87, and a CNAC plane. They also damaged three others. Despite more U.S. fighter patrols, more C-46s were shot down on October 20, 23, and 27. Japanese pilots called shooting down these unarmed transport planes tsuji-giri ("cutting down a casually met stranger"). The Tenth Air Force immediately attacked Japanese airfields. The ICW also moved its route to Kunming even farther north.

Hardin changed how things were done. He started night missions and refused to cancel flights due to bad weather or enemy threats. Even though more planes were lost to accidents and enemy action, the amount of cargo delivered rose sharply. The operation finally met its goal in December, delivering over 12,500 tons to Kunming. This was after new C-46s, loaded with much-needed spare parts, started arriving. By the end of 1943, Hardin had 142 planes: 93 C-46s, 24 C-87s, and 25 C-47s.

Because of these efforts, President Roosevelt ordered the Presidential Unit Citation for the India-China Wing. Hardin was promoted to brigadier general and received the award in January 1944. This was the first time a non-combat unit received this honor.

In June 1944, the Japanese fighter base at Myitkyina was captured. This removed a major threat to Allied planes flying the Hump. This allowed Douglas C-54 Skymaster planes to use a second, more direct route, unofficially called the "Low Hump." The C-54s could not fly over the highest mountains.

On July 1, 1944, the ATC reorganized. The ICW-ATC became the India China Division ATC (ICD-ATC). The Eastern Sector, which handled the India-China airlift, became the Assam Wing.

Tunner Takes Command (1944-1945)

Brigadier General William H. Tunner took command of the India-China Division on September 4, 1944. His orders were to increase cargo delivery, reduce accidents, and improve morale. Tunner and his team used a "big business" approach. They completely changed the operation, improved morale, and cut aircraft losses in half. They also doubled the amount of cargo delivered.

Tunner used over 47,000 local workers. He even used an elephant to lift 55-gallon fuel drums into planes! A daily direct flight called the "Trojan" carried top-priority supplies or passengers between Calcutta and Kunming. It also brought back wounded patients or engines needing repair. Each base had daily and monthly cargo goals based on their planes and distance from China. Tunner also brought back strict military rules for dress and behavior.

In Tunner's first month, the ICD delivered 22,314 tons to China. But it still had a high accident rate. By January 1945, Tunner's division had 249 planes and 17,000 people. That month, they delivered over 44,000 tons of cargo and passengers. However, they also had 23 fatal crashes, killing 36 crewmen. On January 6, a fierce winter storm hit the Himalayas. This caused 14 CNAC and ATC planes to be lost, with 42 crewmen missing. This was the highest one-day loss of the operation.

To reduce losses from mechanical problems, Tunner started "Production Line Maintenance" in February 1945. This meant planes were towed through different stations for maintenance. Each station had a fresh crew trained for a specific task. This process took almost 24 hours per plane. Each base specialized in only one type of aircraft to make it simpler.

Tunner also worked to reduce accidents from inexperience and tired crews. He appointed Lieutenant Colonel Robert D. "Red" Forman to oversee training and a flying safety program. Tunner also changed the rules for how long pilots had to serve. Before, a pilot's tour ended after 650 flight hours over the Hump. Many pilots flew daily to reach this limit in as little as four months. But this made them overworked. The division flight surgeon reported that half of all crewmen suffered from fatigue. So, starting March 1, 1945, Tunner increased the required flight hours to 750. He also required all personnel to be in the theater for twelve months to be eligible for rotation. This stopped pilots from over-scheduling themselves.

Under Tunner, the India-China Division grew to four wings by December 1944. This was needed to manage the many new airfields. Besides the Assam and India Wings, ICD added the Bengal Wing (for C-54 operations) and the China Wing at Kunming.

Both the accident rate and the number of accidents decreased significantly. Tunner called for C-87s and C-109s to be replaced by C-54s. Plans were made to increase the C-54 force to 272 by October 1945.

In July 1945, the last full month of operations, the India-China airlift delivered 71,042 tons. This was ICD's highest monthly tonnage ever. Of this, 332 were ICD transport planes, but 261 were combat aircraft temporarily helping the airlift. About 332 flights to China were scheduled daily. The India-China Division ATC had 34,000 USAAF personnel. Including local civilians, 84,000 people worked for the airlift. More than 85% of the planes were ready to fly at any time. ICD had 23 major accidents in July, with 37 crewmen killed. But the Hump accident rate dropped to 0.358 planes lost per thousand hours of flight in July.

On August 1, 1945, for "Air Force Day," ICD flew its largest mission. Tunner wrote that ICD flew 1,118 round-trip flights, averaging two per plane. One C-54 made three round trips in 22¼ hours. 5,327 tons were delivered in one day without any deaths or major accidents. Tunner considered ICD's safety record his greatest achievement.

Tunner commanded the division until November 10, 1945. The division was disbanded on November 15, 1945.

Supporting Other Operations

Help for Ground Forces

From February 1944, the India-China Wing also helped with other operations. Japanese attacks in Arakan and against Imphal in March and April led to the ICW helping the British. This reduced Hump deliveries by an estimated 1,200 tons. The threat to Imphal also endangered the Assam-Bengal railroad, which carried Hump cargo and fuel for the airlift.

Admiral Louis Mountbatten, the Allied commander, asked for 38 C-47 planes to reinforce Imphal. ICW provided 25 C-46s, which were equal to 38 C-47s. These planes helped move the 5th Indian Division to Imphal and Dimapur. They arrived in time to stop the Japanese attack.

The next month, to support General Stilwell's attack into Burma, the ICW flew 18,000 Chinese troops across the Hump to Sookerating. This reduced the India-China effort by at least 1,500 tons. However, in May 1944, American and Chinese troops captured the Myitkyina airfield. This took away the main Japanese fighter base that threatened Allied planes flying the Hump. The airfield immediately became an emergency landing strip for Allied planes.

Supporting B-29 Bombers

From April 1944 to January 1945, the India-China Division also supported Operation Matterhorn. This was a B-29 Superfortress bombing campaign against Japan from bases around Chengtu in central China. The B-29s were supposed to carry their own fuel and supplies. But this plan didn't work well. The B-29 force was smaller than planned. B-29s were stripped of guns and fitted with extra fuel tanks to carry fuel. But they couldn't bring enough supplies from their bases in India to start missions. So, the XX Bomber Command asked ICD for more help.

Of the 42,000 tons of supplies delivered before the B-29s left China, ICD moved almost two-thirds. During the last three months of bombing from China, ICD supplied almost all of the XX Bomber Command's materials, except for bombs.

Challenges of Flying The Hump

Building the Airlift Capacity

Creating the airlift was a huge challenge for the Tenth Air Force in April 1942. They had no units for moving cargo, no experience with organized airlifts, and no airfields for planes. Also, flying in the region was difficult because there were no good maps, no radio navigation aids, and little weather information.

In 1942, Chiang Kai-shek said China needed at least 7,500 tons of supplies each month. But this goal was not met for the first 15 months. The 7,500-ton goal was first passed in August 1943. By then, the goal had increased to 10,000 tons a month. Eventually, monthly needs went over 50,000 tons.

Slowly, an airlift of incredible size began to form. Four new bases were started in 1942. By 1944, the operation flew from six all-weather airfields in Assam. By July 1945, the air corridor from India started at 13 airfields in the Brahmaputra valley. It ended at six airfields around Kunming in China.

Until July 1944, the flight corridor for the India-China airlift was 50 miles wide with strict height limits. As bases grew and the Low Hump route was used, the corridor widened to 200 miles. It had 25 charted routes, allowing busy but controlled flights at all hours.

Aircraft Problems

A big problem was finding a cargo plane that could carry heavy loads at the high altitudes needed. Three types were tried before the Low Hump route allowed C-54s. These were the C-47, C-46, and C-87/C-109.

At first, the airlift used the Douglas DC-3 and its military versions, the C-47 and C-53. However, the DC-3's body was too high off the ground, making loading difficult. Its narrow door and weak floor couldn't handle heavy cargo. C-47s had stronger floors and wider doors, but they still needed special equipment for heavy loads and had limited capacity. Also, these planes weren't designed for high-altitude flights with heavy loads. They often couldn't fly high enough to clear the mountains, forcing them to use dangerous routes through mountain passes.

In January 1943, the Consolidated C-87 Liberator Express was introduced. This was a modified B-24D Liberator bomber. It helped increase cargo tonnage. It could fly high enough to go over the lower mountains (15,000–16,000 feet). But this plane had a high accident rate and wasn't suited for the airfields used then. Even with four engines, the C-87 climbed poorly with heavy loads and often crashed on takeoff if an engine failed. Its poor cockpit lights made bad weather flying hard. Its electrical and hydraulic systems often froze at high altitude. Pilots said it tended to spin out of control in even mild ice over the mountains.

Another Liberator transport, the C-109, carried gasoline. These were converted B-24J or B-24L bombers. They had eight fuel tanks inside the plane. Most of the 218 C-109s served in the CBI under ATC. At least 80 were in major accidents between September 1944 and August 1945. Crews didn't like them because they were hard to land when full. A crash landing of a loaded C-109 always exploded, killing the crew. This earned it the nickname "C-One-Oh-Boom."

The Curtiss C-46 Commando started flying India-China missions in May 1943. The C-46 was a large twin-engine plane. It could fly faster and higher than earlier cargo planes. It could also carry heavier loads than the C-47 or C-87. With the C-46, airlift tonnage increased a lot. It passed its goals with 12,594 tons in December 1943. Cargo loads kept increasing through 1944 and 1945, reaching a record high in July 1945.

Even though it became the main medium-range plane for the Hump airlift, the C-46 often had mechanical failures. Its engines often failed, and fuel leaks were common. These leaks would collect at the wing root, creating an explosion risk. Crews sometimes called it the "flying coffin." In its first five months, 20% of the C-46s crashed. When it first arrived, it needed 50 field changes before it could fly. It also needed extra training for new crews. Worse, spare parts were so scarce that 26 of the first 68 C-46s were out of service.

Dangers of Flight

Flying over the Hump was extremely dangerous for Allied flight crews. The air route went through high mountains and deep valleys between north Burma and west China. Here, strong turbulence, 125 to 200 mph winds, ice, and bad weather were common. A lack of good navigation equipment, radio beacons, and enough trained people made airlift operations difficult.

In the first year, inexperienced officers often overloaded planes. They didn't know about weight limits. Most pilots were reserves from airlines with little military transport experience. They were used to civilian safety rules. As the airlift grew in 1943, most new pilots were just out of flight school. They had little experience flying by instruments. This meant the ICW had to create a training school in India. This took 16 experienced pilots and eight to ten planes away from the airlift. CNAC pilots also had little instrument experience.

American and CNAC pilots often flew daily, round-trip flights, sometimes around the clock. Some tired crews flew as many as three round trips every day. Mechanics worked on planes outdoors, using tarpaulins to cover engines during heavy rains. They also got burns from sun-heated metal. There weren't enough mechanics or spare parts for the first two years. Maintenance was often delayed. Many overloaded planes crashed on takeoff after losing an engine or having other mechanical problems. Author and ATC pilot Ernest K. Gann saw four crashes in one day at Chabua: two C-47s, two C-87s, and 32 people killed. He said it was "Not to be confused with a combat operation." Because the area was so isolated and the CBI theater had low priority, parts were scarce. Crews often had to go to crash sites in the Himalayan foothills to take parts from wrecked planes. Sometimes, monthly plane losses were 50% of all planes flying the route. A side effect of the many crashes was a local boom in crafts made from aluminum plane debris.

Besides losses from weather and mechanical failure, unarmed transport planes flying the Hump were sometimes attacked by Japanese fighters. Once, while flying a C-46, Lieutenant Wally A. Gayda fired a Browning automatic rifle out the cockpit window at a fighter. He killed the Japanese pilot. Some C-87 pilots put .50 caliber machine guns in front of their cargo doors. But there are no records of them being used.

Search and Rescue Efforts

The high number of losses led to the creation of one of the first search and rescue groups in July 1943. It was nicknamed "Blackie's Gang." Captain John L. "Blackie" Porter, a former test pilot and Hump veteran, led the unit. They used C-47s borrowed from airlift units. The crews were former barnstormers and enlisted personnel armed with submachine guns and hand grenades. "Blackie's Gang" rescued almost every crewman in 1943. This included CBS News reporter Eric Sevareid and 19 others who had to parachute on August 2. The unit moved to Chabua on October 25. It was given official status and two C-47s and several L-5 Sentinel liaison planes for rescues. Porter recruited volunteer medics to parachute into crash sites to help injured crewmen.

When Tunner took command, he wasn't happy with the search-and-rescue setup. He called it "a cowboy operation." He appointed Major Donald C. Pricer to create "a thorough and efficient search and rescue organization." Pricer's 90 men of the 1352nd Base Unit (Search and Rescue) at Mohanbari used four B-25s, a C-47, and an L-5. These planes were painted yellow with blue wing bands for easy identification. Pricer also mapped all known crash sites to avoid checking old wrecks. Sometimes, he called on a Sikorsky YR-4 helicopter from Myitkyina to help with rescues.

Airlift Statistics

ATC operations carried 685,304 gross tons of cargo eastward during the war. This included 392,362 tons of gasoline and oil. Almost 60% of that total was delivered in 1945. ATC planes made 156,977 trips eastward between December 1, 1943, and August 31, 1945. During this time, 373 planes were lost. The airlift delivered a total of 650,000 net tons. This was much more than the Ledo Road (147,000 tons), which opened in January 1945. Besides cargo, 33,400 people were transported.

CNAC pilots made a key contribution. Between 1942 and 1945, the Chinese received 100 transport planes from the United States: 77 C-47s and 23 C-46s. Of the total 776,532 gross tons carried over the Hump, CNAC pilots carried 75,000 tons (about 12%). The India-China airlift continued after the war ended. The final missions of the ICD were to transport 47,000 U.S. personnel westward over The Hump from China to Karachi to return to the United States.

General Tunner's final report said that the airlift "expended" 594 aircraft. At least 468 American and 41 CNAC planes were known lost. 1,314 air crewmen and passengers were killed. Another 81 planes were never found, with 345 personnel listed as missing. About 1,200 personnel were rescued or walked back to base on their own.

The total flight time for the airlift was 1.5 million hours. The India-China ferrying operation was the largest and longest strategic air bridge in history by cargo volume. It was only surpassed in 1949 by the Berlin airlift, which was also commanded by General Tunner.

Notable People Who Flew The Hump

- Barry Goldwater, who later became a U.S. Senator and presidential candidate, was a pilot and flight instructor.

- Robert Lee Scott, Jr., was a pilot and commanding officer.

- Merian C. Cooper, a movie producer, was a liaison officer.

- Robert S. McNamara, who later became Secretary of Defense, was a scheduling analyst.

- Thomas Watson Jr., who became CEO of IBM and an ambassador, was a lieutenant colonel.

- Ernest K. Gann, a famous author, was a C-87 instructor pilot.

- Richard E. Cole, a Doolittle Raider, was a pilot.

- Theodore F. Stevens, who became a U.S. Senator, was a C-47/C-46 pilot.

- Gene Autry, a famous television and movie star, was a C-109 pilot.

Images for kids

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |