Common tsessebe facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Common tsessebe |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| A tsessebe in Botswana | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Damaliscus |

| Species: | |

| Subspecies: |

D. l. lunatus

|

| Trinomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus lunatus (Burchell, 1824)

|

|

|

|

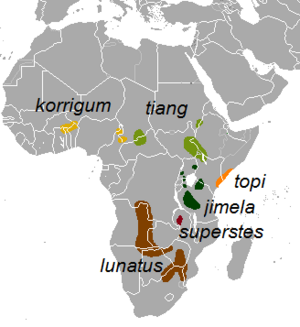

| Range in brown | |

The common tsessebe (pronounced "sess-see-bee") or sassaby is a type of antelope found in southern Africa. Its scientific name is Damaliscus lunatus lunatus. These amazing animals are known for being one of the fastest antelopes in Africa. They can run at speeds up to 90 kilometers per hour (about 56 miles per hour)!

You can find common tsessebe in countries like Angola, Zambia, Namibia, Botswana, Zimbabwe, Eswatini (which used to be called Swaziland), and South Africa.

Contents

What Does a Tsessebe Look Like?

Adult tsessebe are quite large. They can be between 150 to 230 centimeters (about 5 to 7.5 feet) long. Males usually weigh around 137 kilograms (about 302 pounds), and females weigh about 120 kilograms (about 265 pounds).

Both male and female tsessebe have horns. Female horns are about 37 centimeters (14.5 inches) long, while male horns are a bit longer, around 40 centimeters (15.7 inches). For males, their horns are important for defending their space and attracting mates.

Their bodies are a beautiful chestnut brown color. The front of their faces and the tuft of hair on their tails are black. Their front legs and thighs are grayish or bluish-black, while their back legs are brownish-yellow to yellow. Their bellies are white.

In the wild, tsessebe can live up to 15 years. However, in some places, their lives are shorter because of too much hunting and their homes being destroyed.

How Do Tsessebe Behave?

Tsessebe are very social animals. Female tsessebe live in groups with their young, usually with six to ten members. When young males turn one year old, they leave their birth herd. They then form their own groups called "bachelor herds," which can have up to 30 young males.

Adult male tsessebe also form herds, but these are mainly for creating special areas called "leks" where they compete for mates.

Marking Their Territory

Tsessebe have many ways to show that an area is their territory. They might stand very tall, lift their legs high when walking, or grunt. They also mark their territory by pooping in a crouched position, digging their horns into the ground, or rubbing their shoulders on things.

One interesting way they mark their territory is by rubbing their foreheads and horns with a special liquid from glands near their eyes. They do this by putting grass stems into these glands to get the liquid, then waving the grass around to spread the liquid onto their heads and horns.

Peculiar Habits

Scientists have noticed some strange behaviors in tsessebe. For example, when they sleep, tsessebe sometimes rest their mouths on the ground with their horns pointing straight up in the air. Male tsessebe have also been seen standing in rows with their eyes closed, bobbing their heads back and forth. Scientists are still trying to figure out why they do these things!

What Do Tsessebe Eat and Where Do They Live?

Tsessebe mostly eat grass. They live in grasslands, open plains, and savannas with some trees. You can also find them in rolling hills, but rarely in flat plains below 1500 meters (about 4,900 feet) above sea level.

In places like the Serengeti, tsessebe usually eat in the morning, between 8:00 and 9:00 am, and again in the afternoon, after 4:00 pm. The time before and after eating is spent resting, digesting their food, or finding water during dry seasons. Tsessebe can travel up to 5 kilometers (about 3 miles) to find water. To avoid other tsessebe, they often travel along the edges of territories. This can make them more open to attacks from predators like lions and leopards.

How Do Tsessebe Reproduce?

Female tsessebe usually have one calf each year. Calves become old enough to have their own young when they are two to three and a half years old. After mating, a female tsessebe carries her baby for seven months. The "rut," which is the time when males compete for females, happens from mid-February through March.

The Lek System

The breeding process often starts with the creation of a "lek." A lek is a special area where adult male tsessebe gather. Females visit these leks only to choose a mate. What's interesting about leks is that females choose their mate without the male directly influencing them.

Males group together in the middle of the lek for several reasons:

- Being in a group can help protect them from predators.

- If males gather in an area with little food, it means less competition for food between males and females.

- Grouping together gives females more males to choose from in one central spot.

The strongest males usually stay in the center of the lek. This means females are more likely to mate with males in the middle than with those on the edges. To reach the center, a male must be strong enough to win against other males. Staying in the center can be tough, as males often get hurt defending their spot from hyenas and other males.

Where Did the Name "Tsessebe" Come From?

The first person from the Western world to paint this antelope was an English artist named Samuel Daniell. He called it the "sassayby." Later, by the end of the 1800s, "sassaby" was a common name for this antelope in Southern Africa.

The English later learned the Tswana name for the antelope, which was tsessĕbe. By 1895, people thought this was where the English word "tsessebe" came from. Other local names for the antelope were also recorded, like inkweko, incolomo, unchuru, and myanzi. The name "common tsessebe" was created in 2005 to help tell it apart from another similar type of antelope.

Is the Tsessebe Endangered?

In 1998, experts estimated there were about 30,000 tsessebe in total. At that time, they were considered "lower risk" for extinction. More recently, in 2016, the population in South Africa was estimated to be at least 2,256 to 2,803 individuals.

During the 1980s and 1990s, tsessebe numbers in South Africa and Zimbabwe went down. But by 1999, their populations started to grow again, especially in private game reserves. Scientists have studied why the numbers declined. One idea is that other antelope species became more common, partly because of man-made watering holes in game parks. Closing some of these watering holes might help tsessebe by creating more varied habitats.

The number of tsessebe on private game reserves has grown quickly, especially in the 2010s. This is helping the species recover in South Africa. However, there are some concerns that tsessebe might breed with red hartebeest, another native antelope, which could mix their genes.

In northern Botswana, however, tsessebe populations decreased from 1996 to 2013. For example, in the Okavango Delta, their numbers dropped by 73%.

Images for kids

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |