Damaliscus lunatus facts for kids

Quick facts for kids Topi |

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Tsessebe in Botswana | |

| Conservation status | |

| Scientific classification |

|

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Mammalia |

| Order: | Artiodactyla |

| Family: | Bovidae |

| Subfamily: | Alcelaphinae |

| Genus: | Damaliscus |

| Species: |

D. lunatus

|

| Binomial name | |

| Damaliscus lunatus (Burchell, 1824)

|

|

|

|

| Damaliscus lunatus | |

| Script error: The function "autoWithCaption" does not exist. | |

Script error: No such module "Check for conflicting parameters".

The Damaliscus lunatus, also known as the topi, sassaby, tiang, or tsessebe, is a large African antelope. It belongs to the Bovidae family, which includes cattle, goats, and sheep. Topi are known for their reddish-brown coats, dark markings, and ringed horns. They live in grasslands across parts of Africa.

Contents

What's in a Name?

The name topi comes from the Swahili word tope. A German explorer named Gustav Fischer first wrote down this name. He heard it on the island of Lamu off the coast of Kenya. Other names for this antelope have been used in different African languages.

Different Kinds of Topi

Scientists first officially described the topi in 1824. They called it the "crescent-horned antelope." Over time, people found different groups of topi in various parts of Africa. These groups look a bit different from each other.

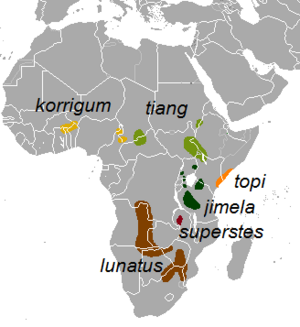

For a long time, most scientists thought there were five main types, or subspecies, of topi. However, some scientists believe these different groups should be considered separate species. This means they think some topi groups are distinct enough to be their own kind of animal. This idea is still debated among experts. As of 2021, many scientists still see the topi as one species with different subspecies.

The Topi Subspecies

One well-known type of topi lives north of Lake Bangweulu in Zambia and near Lake Rukwa in Tanzania. This subspecies is usually called the 'topi'. It has horns that curve like a lyre, which is a type of harp.

Appearance and Size

Adult topi are quite large. They can be about 150 to 230 centimeters (5 to 7.5 feet) long. Males usually weigh around 137 kilograms (302 pounds), and females weigh about 120 kilograms (265 pounds). Their horns can be up to 40 centimeters (16 inches) long for males. Males use their horns to defend their space and attract mates.

Topi have a reddish-brown or chestnut-brown body. Their faces have dark, mask-like markings. Their tail tufts are black, and their upper legs have dark patches. Their lower legs are yellowish, and their bellies are white. In the wild, topi can live up to 15 years, but most live for a shorter time.

Topi look similar to hartebeest but are darker. They have long heads and a small hump at the base of their neck. Their horns are ringed and curve backward and then up. Their fur is short and shiny. Topi also have special glands near their eyes that produce a clear oil.

Tsessebe Differences

The tsessebe is the southernmost type of topi. Its horns are placed a bit differently than other topi. They spread out more, making the space between them look like a crescent moon. Tsessebe in South Africa tend to be lighter in color and a bit smaller. Those in Zambia are often darker with stronger horns.

Where Topi Live

Topi live in parts of Southern, East, and West Africa. They prefer open grasslands and savannas. They are often found in large numbers in certain areas, or not at all. Human activities, like hunting and changing their habitat, have made their populations more scattered.

The health of a topi group depends on having enough green plants to eat. Topi herds often move between different feeding areas. A very large migration happens in the Serengeti, where topi join huge herds of wildebeests, zebras, and gazelles.

Male topi set up their own territories. These areas can be quite large, up to 4 square kilometers (1.5 square miles). Females with their young are attracted to these territories.

How Topi Live

Their Home

Topi mostly live in grasslands, open plains without trees, and savannas with light woods. They like flat, low areas. They are rarely found higher than 1500 meters (about 4,900 feet) above sea level. If there are woods nearby, they might stay at the edge for shade when it's hot. Topi often use high spots, like termite mounds, to look out for danger.

Studies show that topi are quite picky about their homes. They really like grasslands that get dry at certain times of the year. In Botswana, they spend most of their time in open areas. But during the rainy season, they might move into mopane woodlands.

What They Eat

Topi are grazing animals, which means they eat mostly grass. They are picky eaters and use their long snouts and flexible lips to find the youngest, freshest blades of grass. Topi are not good at eating very short grass. During the rainy season, they avoid both very tall, old grass and very short grass. In the dry season, they look for any area with the most grass.

If they have enough green plants, topi usually don't need to drink water. They drink more when they are eating dry grass. In the Serengeti, topi usually eat in the morning and late afternoon. The time before and after eating is for resting and digesting. Topi might travel up to five kilometers (3 miles) to find water. They often travel along the edges of territories to avoid fights.

Who Hunts Them?

The main predators of topi include lions, cheetahs, african wild dogs, and spotted hyenas. Young topi calves can also be hunted by jackals. Hyenas especially target topi. However, topi are less likely to be hunted if other animal species are also present in the area.

Topi Behavior

Topi use different actions to show that an area is their territory. These include standing tall, high-stepping, pooping in a special crouch, digging their horns into the ground, and rubbing their shoulders.

One important way they show dominance is by horning the ground. Another strange way they mark territory is by rubbing their foreheads and horns with a special oil from glands near their eyes. They might even use grass stems to help spread the oil. When a male topi is away, a dominant female might act like him. She will defend the territory from other topi.

Scientists have noticed some unusual topi habits. For example, they sometimes sleep with their mouths on the ground and their horns pointing straight up. This might be a small way to protect themselves while sleeping. Male topi have also been seen standing in rows with their eyes closed, bobbing their heads. Scientists are still trying to figure out why they do these things.

How They Reproduce

Topi usually have one calf each year.

The breeding process often starts with males gathering in special areas called leks. Females visit these leks only to find a mate. The most dominant males usually stay in the center of the lek. Females are more likely to mate with these central males.

Males group together in leks for a few reasons. First, being in a group can help protect them from predators. Second, if males gather in an area with little food, it means less competition for food between males and females. Finally, grouping together gives females more choices for a mate in one spot.

A male's mating success is often higher the closer he is to the center of the lek. To get to the center, a male must be strong enough to win against other males. Once a male has a territory in the middle, he usually keeps it for a while. However, defending a central spot can lead to injuries from hyenas or other males.

In places like Akagera National Park in Rwanda, male topi create leks where their territories are close together. These territories are not valuable for food, only for mating. The strongest males are in the middle, and less strong ones are on the edges. Males mark their territories with piles of dung and stand tall, ready to fight. Females ready to mate enter the leks and choose males in the center. Females will even compete with each other for the most dominant males.

Young topi calves can follow their mothers right after birth. However, females often leave the herd to give birth. Calves might also hide at night. A young topi stays with its mother for about a year, or until a new calf is born. Young males and females can be found in groups of bachelors.

Conservation Status

The total number of topi was estimated to be around 400,000 in 2016. The IUCN (International Union for Conservation of Nature) has assessed the topi as 'least concern'. This means they are not currently in danger of extinction. However, the IUCN still believes that the overall number of topi is slowly going down.

Common Tsessebe Status

In 1998, there were about 30,000 tsessebe. In South Africa and Zimbabwe, tsessebe populations decreased in the 1980s and 1990s. But around 1999, their numbers started to grow again, especially on private game reserves.

One reason for the past decline might have been too many trees growing in their grassland homes. Another idea is that competition with other antelope species played a role. Closing some man-made watering holes in parks might help the tsessebe by creating better habitats for them.

In recent years, the number of tsessebe on private game reserves has grown quickly. This is good for the species' recovery in South Africa. However, there is some concern that tsessebe might breed with red hartebeest, which are also native to the area. This could potentially mix up their genes in the future.

In northern Botswana, however, tsessebe populations have gone down. For example, in the Okavango Delta, their numbers dropped by 73% between 1996 and 2013.

Related pages

- Topi, a highly social and fast type of antelope found in the savannas, semi-deserts, and floodplains of sub-Saharan Africa.