D. T. Suzuki facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

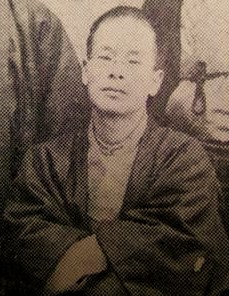

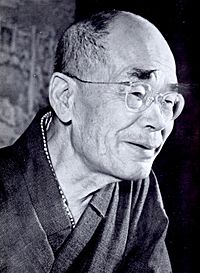

D. T. Suzuki

|

|

|---|---|

circa 1953

|

|

| Born | 18 October 1870 Honda-machi, Kanazawa, Japan |

| Died | 12 July 1966 (aged 95) Kamakura, Japan |

| Occupation | Buddhist monk, university professor, essayist, philosopher, religious scholar, translator, writer |

| Notable awards | National Medal of Culture |

Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki (鈴木 大拙 貞太郎, Suzuki Daisetsu Teitarō, 18 October 1870 – 12 July 1966) was a Japanese Buddhist monk, writer, and teacher. He was known for sharing the ideas of Buddhism, especially Zen and Shin Buddhism, with people in Western countries.

Suzuki wrote many books and essays. He also translated important texts from Chinese, Japanese, and Sanskrit literature. He taught at universities in both Japan and the West for many years. In 1963, he was even nominated for the Nobel Peace Prize.

Contents

Biography

Early Life and Studies

D. T. Suzuki was born Teitarō Suzuki in Kanazawa, Japan. He was the fourth son of a doctor. His Zen teacher, Soyen Shaku, gave him the Buddhist name Daisetsu. This name means "Great Humility."

Suzuki's family belonged to the samurai class. But this class lost its power when feudalism ended in Japan. After his father died, his mother, a Jōdo Shinshū Buddhist, raised him in difficult times. As he grew up, he looked for answers to life's big questions in different religions.

Suzuki studied at Waseda University and University of Tokyo. He learned many languages, including Chinese, Sanskrit, Pali, and several European languages. While at Tokyo University, he started practicing Zen at Engaku-ji temple in Kamakura.

He later lived and worked with an American scholar named Paul Carus in Illinois. Suzuki helped Carus translate old Eastern writings into English. One of their first projects was translating the Tao Te Ching. Suzuki also wrote his early book, Outlines of Mahayana Buddhism, during this time.

Carus had written a book about Buddhism called The Gospel of Buddha. Suzuki translated this book into Japanese. Around this time, many people in both the West and Asia were interested in a worldwide Buddhist revival.

Marriage and Career

In 1911, Suzuki married Beatrice Erskine Lane Suzuki. She was a graduate of Radcliffe College and interested in Theosophy. Suzuki himself later joined the Theosophical Society.

After living in the United States and traveling in Europe, Suzuki returned to Japan. In 1909, he became a professor at Gakushuin University and the University of Tokyo. He and his wife worked to help people understand Mahayana Buddhism.

In 1921, Suzuki became a professor at Ōtani University in Kyoto. That same year, he and his wife started the Eastern Buddhist Society. This group gives talks and workshops on Mahayana Buddhism. They also publish a scholarly magazine called The Eastern Buddhist. Suzuki kept in touch with people in the West. For example, he gave a speech at the World Congress of Faiths in London in 1936.

Suzuki was an expert on Zen Buddhism and its history. He also studied a related philosophy called Kegon in Japanese. He believed Kegon helped explain the deep experiences of Zen.

Suzuki received many awards for his work. One of the highest was Japan's National Medal of Culture.

Teaching and Writings

In the mid-1900s, Suzuki was a well-known professor of Buddhist philosophy. He wrote many books that introduced and explained Buddhism, especially the Zen school. He went on a lecture tour of American universities in 1951. He also taught at Columbia University from 1952 to 1957.

Suzuki was very interested in how Zen Buddhism developed in China over hundreds of years. Many of his English writings discuss and translate parts of famous Zen texts. These include the Biyan Lu (Blue Cliff Record) and the Wumenguan (Gateless Passage). These books share the teachings of old Chinese Zen masters.

He also explored how Zen influenced Japanese culture and history. He wrote about this in his book Zen and Japanese Culture.

Besides his popular books, Suzuki translated the Lankavatara Sutra. This is an important Buddhist text. In his later years, he also explored the Jōdo Shinshū faith, which was his mother's religion. He gave talks on Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism in America.

Suzuki started translating the Kyogyoshinsho, a major work by Shinran, who founded the Jōdo Shinshū school. He believed Jōdo Shinshū Buddhism was a "most remarkable development" of Mahayana Buddhism in East Asia. Suzuki was also interested in Christian mysticism and compared it to the Jōdo Shinshū followers called Myokonin. He was one of the first to introduce the Myokonin to people outside Japan.

Other important books by Suzuki include Essays in Zen Buddhism (three volumes), Studies in Zen Buddhism, and Manual of Zen Buddhism.

Suzuki's Ideas on Zen

Suzuki's Zen teacher, Soyen Shaku, believed Zen came from Mahayana Buddhist roots. Suzuki, however, thought that Zen (or Chan) in China had also taken in many ideas from Chinese Taoism. Suzuki believed that people in the Far East were more connected to nature than people in Europe or Northern India.

Suzuki thought that religions are like living things. They can change and grow over time.

He believed that a Zen "awakening" (a sudden understanding) was the main goal of Zen training. But he also said that Zen in China developed a way of life very different from Indian Buddhism. In India, monks often begged for food. In China, temples became training centers where monks did everyday tasks. These tasks included gardening, carpentry, cleaning, and helping the community. This meant that Zen enlightenment had to work well with the challenges of daily life.

Suzuki is often connected to the Kyoto School of philosophy, but he was not an official member. He was interested in many Buddhist traditions, not just Zen. His book Zen and Japanese Buddhism explored the history of all the main Japanese Buddhist schools.

Zen Training

While studying at Tokyo University, Suzuki began Zen practice at Engaku-ji. This is one of Kamakura's famous temples. He first studied with Kosen Roshi. After Kosen passed away in 1892, Suzuki continued his studies with Kosen's student, Soyen Shaku.

Under Rōshi Soyen, Suzuki's studies were very personal and focused on inner experience. This included long periods of sitting meditation. Suzuki said this training was a four-year struggle for his mind, body, and spirit. During his training at Engaku-ji, Suzuki lived like a monk. He described this life in his book The Training of the Zen Buddhist Monk. He said the training involved humility, hard work, service, prayer, gratitude, and meditation.

Soyen Shaku invited Suzuki to visit the United States in the 1890s. Suzuki helped translate a book by Shaku in 1906. This was the start of Suzuki's career as a writer in English.

Later in life, Suzuki became more interested in Jodo Shin (True Pure Land) practice. He saw that the idea of "other power" (Tariki) in this teaching, where you rely on something beyond yourself, was similar to Zen. He felt it was even less about willpower than traditional Zen. In his book Buddha of Infinite Light (2002), Suzuki said that Shin Buddhism was the "most remarkable development of Mahayana Buddhism" in East Asia.

Sharing Zen in the West

Suzuki played a huge role in bringing Zen Buddhism to Western countries.

Modern Buddhism

Suzuki presented Zen Buddhism as a very practical religion. He showed how its focus on direct experience was similar to types of mysticism that scholars like William James believed were at the heart of all religious feelings. This idea of a shared core made Suzuki's ideas easy for Western audiences to understand.

Many scholars see Suzuki as a "Buddhist modernist." This means he presented Buddhism in a way that fit with modern ideas. Buddhist modernism often focuses less on rituals and old beliefs. Instead, it highlights the core ideas of Buddhism as universal truths.

New Buddhism Movement

When Japan began to modernize in the Meiji period (1868), Buddhism faced challenges. The government saw it as an old foreign religion. However, a group of modern Buddhist leaders emerged. They agreed that Buddhism needed to change and become more modern.

This led to the "New Buddhism" movement. It was led by educated thinkers who knew a lot about Western ideas. Leaders like Suzuki's teachers, Imakita Kosen and Soyen Shaku, saw this movement as a way to protect Buddhism and help Japan become a modern, strong nation.

Some scholars believe that the type of Zen Buddhism promoted by these "New Buddhism" thinkers was different from traditional Japanese Zen. Traditional Zen in Japan often required many years of intense study and discipline from monks. Suzuki, as a non-monk, was able to practice Zen in a way that was new for the time, thanks to the New Buddhism movement.

Japanese Nationalism and Zen

During the Meiji period, a philosophy called Nihonjinron became popular. It emphasized the unique qualities of the Japanese people. Suzuki believed that Zen was one of these unique qualities. He saw Zen as the deepest essence of all philosophy and religion. He thought Zen was a special expression of Asian spirituality, which he considered superior to Western ways of thinking.

Praise for Suzuki's Work

Suzuki's books have been widely read and discussed around the world.

See also

- Age of Enlightenment

- Buddhism and Theosophy

- Cambridge Buddhist Association

- Japanese Zen

- Timeline of Zen Buddhism in the United States

- Theosophy

- Zen Narratives

- Zen Studies Society

In Spanish: Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki para niños

In Spanish: Daisetsu Teitaro Suzuki para niños

| Laphonza Butler |

| Daisy Bates |

| Elizabeth Piper Ensley |