Dietrich Eckart facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

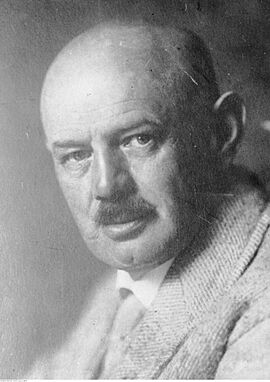

Dietrich Eckart

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| Born | 23 March 1868 Neumarkt, Kingdom of Bavaria |

| Died | 26 December 1923 (aged 55) Berchtesgaden, Bavaria, Weimar Germany |

| Spouse | |

Dietrich Eckart (23 March 1868 – 26 December 1923) was a German writer, poet, and political activist. He helped start the German Workers' Party, which later became the Nazi Party. Eckart greatly influenced Adolf Hitler in the early days of the party. He also started the party newspaper, the Völkischer Beobachter, and wrote the words for their first anthem, "Sturmlied".

In 1923, Eckart took part in a failed attempt to take over the government, known as the Beer Hall Putsch. He died soon after being released from prison due to illness. After the Nazis came to power in 1933, Eckart was seen as a very important thinker. Hitler even called him a co-founder of the Nazi movement and a guide for its early ideas.

Contents

Who Was Dietrich Eckart?

Early Life and Education

Dietrich Eckart was born on 23 March 1868 in Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, a town in Bavaria, Germany. His father, Christian Eckart, was a lawyer. His mother, Anna, was a devoted Catholic. Eckart's mother died when he was ten years old. He was also removed from several schools. In 1895, his father passed away, leaving him a lot of money. Eckart quickly spent it all.

Eckart first studied law at the University of Erlangen-Nuremberg. Later, he studied medicine at the Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich. In 1891, he decided to become a poet, playwright, and journalist. He moved to Berlin in 1899. There, he wrote many plays, often about his own life. He became a student of Count Georg von Hülsen-Haeseler, who was in charge of the Prussian Royal Theatre.

His Play Peer Gynt

As a playwright, Eckart had success with his 1912 version of Henrik Ibsen's play Peer Gynt. This play was performed over 600 times in Berlin. Even though Eckart never had another big hit, Peer Gynt made him wealthy. It also helped him meet important German citizens, which later helped Hitler rise to power.

Eckart's version of Peer Gynt was changed to fit his nationalist and anti-Jewish ideas. In his play, Gynt was a German hero fighting against "trolls," which Eckart meant to represent Jewish people. Eckart believed that Gynt's actions, even if selfish, were noble because he was fighting for a greater cause. Eckart later told Hitler that Gynt's idea of becoming "king of the world" was about a spiritual belief. He suggested that Hitler's goals justified any actions he took.

Eckart's Political Beliefs

Becoming Anti-Jewish

Eckart was not always against Jewish people. In 1898, he even wrote a poem praising a Jewish girl. Before he became anti-Jewish, he admired the poet Heinrich Heine and philosopher Otto Weininger, both of whom were Jewish.

In December 1918, Eckart started an anti-Jewish weekly newspaper called Auf gut Deutsch ("In plain German"). He worked with Alfred Rosenberg and Gottfried Feder. Eckart strongly criticized the German Revolution and the Weimar Republic. He was against the Treaty of Versailles, which he saw as a betrayal. He also supported the idea that Social Democrats and Jewish people were to blame for Germany's defeat in World War I.

Eckart's anti-Jewish views were influenced by a book called The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This book claimed to show a secret Jewish plan to control the world. Many right-wing leaders in Germany believed it was true.

Founding the German Workers' Party

In January 1919, Eckart, Feder, Anton Drexler, and Karl Harrer founded the Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (German Workers' Party, or DAP). To attract more people, the party changed its name in February 1920 to the Nationalsozialistische Deutsche Arbeiterpartei (National Socialist German Workers' Party, or NSDAP), also known as the Nazi Party.

Eckart was important in helping the party buy the Münchener Beobachter newspaper in December 1920. He arranged a loan for 60,000 Marks. The newspaper was renamed the Völkischer Beobachter and became the party's official newspaper. Eckart was its first editor and publisher. He also created the Nazi slogan Deutschland erwache ("Germany awake"). He wrote the words for the anthem based on this slogan, the "Sturm-Lied."

Eckart and Adolf Hitler

Mentoring Hitler

Eckart played a big role in shaping Adolf Hitler's public image. He was one of Hitler's most important early mentors. Their relationship was not just political; they had a strong emotional and intellectual connection. Eckart taught Hitler about the need to fight against "soulless Jewishness" for a true German revolution.

Hitler privately admitted that Eckart was his teacher and mentor. He called Eckart the spiritual co-founder of Nazism. They first met when Hitler gave a speech in late 1919. Eckart was impressed by Hitler and felt he was the right person for their new movement.

Eckart was 21 years older than Hitler. He became like a father figure to a group of younger men, including Hitler. He helped Hitler improve his speaking and writing style. Hitler later said, "Stylistically I was still an infant." Eckart also taught Hitler proper manners.

Hitler and Eckart had much in common, including their interest in art and politics. Both saw themselves as artists. They also shared that their early influences were Jewish, a fact they preferred not to discuss. By the time they met, Hitler wanted to completely remove Jewish people. Eckart believed all Jewish people should be sent away. He also thought that any Jewish man who married a German woman should be jailed.

Eckart helped Hitler meet people in the Munich art scene. He introduced Hitler to painter Max Zaeper and photographer Heinrich Hoffmann. Eckart also introduced Alfred Rosenberg to Hitler. Between 1920 and 1923, Eckart and Rosenberg worked hard for Hitler and the party. Rosenberg and Eckart also influenced Hitler's ideas about Russia. Eckart believed Russia was Germany's natural ally if the Bolshevik government was removed.

In March 1920, Hitler and Eckart flew to Berlin to meet Wolfgang Kapp and take part in the Kapp Putsch. This was Hitler's first airplane flight, and he got airsick. The attempt to take over the government was already failing when they arrived.

Eckart introduced Hitler to wealthy people who could donate money to the Nazi movement. They raised a lot of money in Berlin, where Eckart had many connections. Eckart also introduced Hitler to socialite Helene Bechstein, who helped Hitler meet people in Berlin's upper class.

Changes in Their Relationship

As Hitler became more confident, he needed Eckart less as a mentor. Their relationship became cooler. In November 1922, Eckart and Emil Gansser, a party fundraiser, traveled to Switzerland to meet a rich businessman. The trip was not successful. Hitler blamed Eckart for the failure.

In early 1923, Eckart went to the Bavarian Alps near Berchtesgaden to avoid arrest. Hitler visited him there in April. This was Hitler's first visit to the area where he would later build his mountain home, the Berghof.

Hitler had replaced Eckart as the publisher of the Völkischer Beobachter with Alfred Rosenberg. However, Hitler still spoke highly of Eckart. Despite this, tensions grew between them. Hitler was annoyed that Eckart did not believe a takeover attempt in Munich could lead to a national revolution. Eckart said, "Munich is not Berlin. It would lead to nothing but ultimate failure."

Even though Eckart helped promote Hitler as a genius, he complained in May 1923 that Hitler had "megalomania." This was after Hitler compared himself to Jesus. Despite these issues, Hitler remained close to Eckart and continued to visit him.

Hitler as a Savior

Eckart promoted Hitler as Germany's coming savior. Eckart believed that a "genius" was needed to rid the world of the influence of Jewish people. Many Germans were looking for a savior to lead them out of the country's economic and political problems after World War I.

Under Eckart's guidance, Hitler began to see himself as this special person. Because people believed geniuses were born, not made, Hitler did not publicly mention that Eckart and others had mentored him. In his book Mein Kampf, Hitler did not mention Eckart.

After the Nazi Party bought the Völkischer Beobachter in December 1920, Eckart and Rosenberg used the newspaper to spread the idea that Hitler was a superior being, a divine German Messiah. The newspaper called Hitler "Germany's leader," not just the party leader. This idea of Hitler's specialness began to spread.

Death and Legacy

Dietrich Eckart died in Berchtesgaden on 26 December 1923 from a heart attack. He was buried in Berchtesgaden's old cemetery.

Even though Hitler did not mention Eckart in the first part of Mein Kampf, he dedicated the second part to him after Eckart's death. Hitler wrote that Eckart was "one of the best, who devoted his life to the awakening of our people." In private, Hitler admitted Eckart's role as his mentor. In 1942, Hitler said, "We have all moved forward since then, that's why we don't see what [Eckart] used to be back then: a polar star." Hitler also told a secretary that his friendship with Eckart was "one of the best things he experienced in the 1920s."

Memorials and Monuments

During the Nazi era, several monuments were created for Eckart. Hitler named the outdoor theater near the Olympic Stadium in Berlin the "Dietrich-Eckart-Bühne" when it opened for the 1936 Summer Olympics. A military unit of the SS was also given the honor-title Dietrich Eckart. In 1937, a school in Emmendingen was renamed the "Dietrich-Eckart secondary school for boys." Several new roads were named after Eckart. All of these names have since been changed.

Eckart's hometown, Neumarkt in der Oberpfalz, was officially renamed "Dietrich-Eckart-Stadt." In 1934, Adolf Hitler opened a monument in his honor in the city park. This monument has since been rededicated to Christopher of Bavaria, a king who was likely born in the town.

In March 1938, when Passau celebrated Eckart's 70th birthday, the mayor announced a Dietrich-Eckart-Foundation. He also said the room where Eckart had been imprisoned would be restored. A street was also named after Eckart.

Eckart's Ideas

Eckart is often called the spiritual father of Nazism. Hitler himself said Eckart was its spiritual co-founder.

Eckart saw World War I not just as a war between nations, but as a holy war between "Aryans" and Jewish people. He believed Jewish people planned the fall of the Russian and German empires. To describe this struggle, Eckart used ideas from Norse legends and the Bible.

In 1925, Eckart's unfinished essay Der Bolschewismus von Moses bis Lenin: Zwiegespräch zwischen Hitler und mir ("Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin: Dialogue Between Hitler and Me") was published after his death. Some historians believe this book shows Hitler's own words and ideas.

Historian Richard Steigmann-Gall noted that Eckart believed Christ was a leader to be copied. Eckart was against the political power of the Catholic Church in Germany. He supported a general idea of "positive Christianity."

Personality

Early Nazi supporter Ernst Hanfstaengl described Eckart as "a perfect example of an old-fashioned Bavarian." Journalist Edgar Ansel Mowrer called him "a strange genius." Eckart spent hours discussing art and the role of Jewish people in history with Hitler. Historian Samuel W. Mitcham called Eckart an "eccentric intellectual" and "extreme antisemite."

Joachim C. Fest described Eckart as a "roughhewn and comical figure." He was known for his "bluff and uncomplicated manner." His goals were to promote "true socialism" and free the country from "interest slavery." Historian Thomas Weber said Eckart had a "jovial but moody nature." John Toland called him "an original raffish man with a touch of genius." He was a "master of coffeehouse polemics."

Works

- "Bolshevism from Moses to Lenin: A Dialogue Between Adolf Hitler and Me" English translation (PDF)

See also

In Spanish: Dietrich Eckart para niños

In Spanish: Dietrich Eckart para niños

| Victor J. Glover |

| Yvonne Cagle |

| Jeanette Epps |

| Bernard A. Harris Jr. |