Dyce Work Camp facts for kids

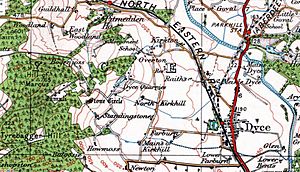

The Dyce Work Camp was a special camp set up in August 1916 during World War I. It was located at some stone quarries northwest of Aberdeen, Scotland. This camp was for conscientious objectors. These were men who refused to join the army because of their beliefs. Most of them were from England and had been in prison for not wanting to fight. They were let out of prison if they agreed to do "work important for the country." At Dyce, this meant breaking up hard granite rock to make stones for roads.

The camp was made of tents near the village of Dyce. Life there was very tough, especially because of the heavy rain. Sadly, one man got very sick with pneumonia and died because he didn't get medical help. After this, people started asking questions. There was an investigation and a discussion in parliament. The camp then closed in October 1916. Officials said it was only meant to be a temporary place.

Contents

Why the Camp Was Needed

Joining the Army: Conscription

When the United Kingdom joined World War I in August 1914, many men eagerly volunteered for the British Army. They felt very patriotic. However, by late 1915, there weren't enough new soldiers. Many had been killed or hurt in the fighting.

So, the government tried a new plan called the Derby Scheme. Men could promise to join the army later when needed. But this still didn't bring in enough volunteers. Because of this, the government decided to make men join the army by law. This was called conscription.

On January 27, 1916, a law called the Military Service Act was passed. It said that all single men aged 18 to 41 in Great Britain had to join the army. Later, in May 1916, married men were also included. Some men were allowed to be excused. This included those doing important war work, like engineers. It also included men doing jobs essential for everyday life, like farmers.

Conscientious Objectors: Refusing to Fight

Local groups called Military Service Tribunals were set up. They listened to men who didn't want to join the army. Reasons could be illness, their job, or being a conscientious objector. It was often hard for these tribunals to decide about conscientious objectors. The law didn't clearly say what a "conscientious objector" was.

Many people, including the tribunals, didn't like "conchies." They often didn't understand why someone would refuse to fight. This was true even for men who had strong moral, political, or religious reasons against war. During the war, over 16,000 men said they were conscientious objectors.

If a man's request to be a conscientious objector was turned down, he was told to join the army. If he refused, he was arrested and sent to a magistrates' court. From there, he was handed over to the army. If he still didn't obey army orders, he faced a court-martial. This meant he was tried by the army and sent to civilian prisons.

There were some famous cases, like the Richmond Sixteen. These men, and 19 others, were sent to France. When they refused to obey orders there, they were sentenced to death. However, this caused a big public outcry. So, the men were saved and sent back to Britain to be imprisoned instead.

Work Centres: A New Plan

Prisons became very crowded with all the conscientious objectors. There were also reports that these men were being treated badly. So, a special committee was formed. It was led by William Brace, a Member of Parliament. This committee decided to create a plan for compulsory work.

It was hard to find regular businesses willing to hire these men. So, many were sent to work on road building or in forests. These were jobs where regular employers weren't involved. Two prisons were even turned into "work centres" for men who couldn't do outdoor work. These work programs were not meant to be a punishment. The idea was that conditions should be similar to what soldiers doing non-fighting jobs at home experienced.

Life at the Dyce Camp

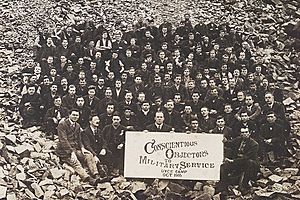

This is how the Dyce Work Camp started. Around August 23, 1916, about 250 men arrived at Dyce Quarries. Their job was to break up granite stones for road construction. Dyce is a few miles northwest of Aberdeen in Aberdeenshire. The quarries were on a hillside just outside the village.

Many of the usual quarry workers had been called up for the war. So, the quarry owner agreed to take on the conscientious objectors. He didn't have to pay their wages. The men were released from prison with clothes and a train ticket. They were trusted to go straight to the camp, and they all did. Thirty-one of these men had been among those sentenced to death in France, including fifteen of the Richmond Sixteen.

The first thing the men had to do was set up their own living space. They put up 27 bell tents and three larger marquees. There were no buildings ready for them. The local council in Aberdeen wasn't told about the camp. The newspapers didn't find out until September 9. A doctor from the Scottish Local Government Board visited the camp on September 4-5. He wrote a detailed report. His report, and a newspaper article from September 12, tell us a lot about the camp.

Working Conditions

The work involved breaking stones. Then, the men used wheelbarrows to take the stones to steam crushers. After crushing, they loaded the small stone pieces into trucks. The plan was for them to work ten hours a day. But at first, they only worked five hours with a one-hour lunch break. This was because many men were not used to hard physical labor. They needed time to build up their strength.

Many of the workers were academics, teachers, or clerks. They had no experience with manual work. They were paid 8 pence a day. This was less than what a soldier earned. Each week, they moved about 1000 tons of granite. That's about 32 truckloads every day.

Living Conditions

The tents they used were old army tents from the Boer War. They were in poor condition and could leak. The doctor noted that even soldiers on the front lines had similar tents. Each man received a mattress filled with straw and three blankets. The water supply was clean and plentiful. The drainage system was also good.

Their food was standard army rations. The doctor thought it was enough. Overall, he believed the camp was okay for a short time. But he warned that wet weather and winter would make better arrangements necessary. About 90 workers chose to sleep in stables or old cottages. Some even paid to stay in local homes.

One man was recovering from scarlet fever and was sent to a hospital. Other illnesses were mostly colds and sore throats.

The Sad Story of Walter Roberts

Walter Roberts was 20 years old. He arrived at Dyce after spending four months doing hard labor in prison. Like many others, he caught a cold soon after arriving at the camp. On Wednesday, September 6, he was too weak to write. He dictated a letter to his mother:

"As I thought, the camp conditions have made me sick. Bartle Wild is writing this for me because I'm too weak to hold a pen. Don't worry, the doctor says it's just a bad chill, but it's made me very weak. Everyone here is very kind and taking care of me. So, I should be strong in a day or two and will write more myself."

The local village doctor had said it was just a chill. But the next night, Roberts fell from his bed. He lay on the wet ground for two hours. The next day, the doctor said he was too sick to be moved. But no nurses or medical care were provided. One of Roberts' friends, who was a dentist, tried to help him. By early Friday, Roberts had died from pneumonia. There was no time to get more medical help. Fenner Brockway, who started the No-Conscription Fellowship and was also a conscientious objector, demanded an investigation. He later became a Member of Parliament.

Checking the Camp

People started demanding a public investigation into Roberts' death and the camp conditions. The Home Office (a government department) decided to do its own internal check. William Brace led a two-hour visit to the camp on September 19. The newspapers were told what they found. They reported it in detail, but the official report was never published.

The visitors decided that all workers should live in barns or lofts. Tents and stable stalls were not good enough. They also said that sick people needed special places to stay. Very sick people should be taken to a hospital. They also said the five-hour workday should continue until living conditions improved. Because of this visit, some improvements were made. The use of tents stopped before the camp closed in October.

Another visitor was Ramsay MacDonald. He later became Prime Minister of Britain. At the time, he was a Member of Parliament for Leicester. He was known for being a pacifist, meaning he was against war. He visited the camp on the same day as the official visit. Newspapers reported that he thought the conditions were "very bad." He also believed that the whole idea of work camps was "wasteful."

Public Opinion and Politics

The opening of the Dyce camp was not announced. But by September, local people knew about the many young "foreigners" arriving. Most of them were Englishmen. The government's policy was to send conscientious objectors far from their homes. So, Scottish objectors were sent far away too.

The workers at Dyce were allowed to leave the camp in their free time. Many of them were well-educated and could speak well. They used this chance to tell people about their situation. They even started a camp newspaper called The Granite Echo.

"Dyce Humbugs"

On September 12, 1916, the Aberdeen Daily Journal newspaper reported Walter Roberts' death. On another page, it published an opinion piece about the conscientious objectors. The headline was "Dyce Humbugs."

The newspaper said that while everyone would be sad about Roberts' death, few would agree with the statements from the conscientious objectors. The objectors had complained about "open-air life in a severe climate" and "ten hours' work in a quarry every day." The newspaper argued that the weather hadn't been severe. It also said that these complaints seemed minor when compared to the conditions soldiers faced in the trenches. Soldiers were fighting and dying for the country. The article called conscientious objectors "degenerates" and "shirkers" of their duty. It also criticized the No-Conscription Fellowship, which supported them.

On the same day, the Aberdeen newspaper also reported on the Battle of the Somme. It listed the daily number of British casualties: 4936, including 1018 killed. There were also short articles about local men who had been killed or wounded.

The Camp Closes

On October 19, during a debate in the House of Commons, both William Brace and Ramsay MacDonald spoke about military service. They talked about Roberts' death and the Home Office investigation. Brace said that the camp was only meant to be temporary. He also said it would cost too much money to improve it to the recommended standards. He announced that the camp would close by the end of the month. The Dyce Work Camp officially closed on October 25, 1916.

Most of the public and local newspapers had been against the camp. They generally didn't approve of the men working there. So, they were happy when the camp closed. After leaving Dyce, the men were sent to other work camps. Some chose to leave the Home Office Scheme and went back to prison instead.

The land where the camp was later became a long-stay car park for Aberdeen Airport.