Economy, industry, and trade of the Victorian era facts for kids

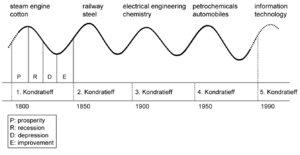

Economy, industry, and trade of the Victorian era is about how the United Kingdom made money and grew during the time Queen Victoria was in charge. This period, known as the Victorian era, saw huge changes in how people lived and worked.

Contents

Amazing Changes

Life in the late 1700s was quite simple, not much different from hundreds of years before. But the 1800s brought incredible new inventions! Someone alive in 1804 would know about the electric telegraph, steam ships, and steam trains. If they lived until 1870, they would have seen the electric light bulb, the typewriter, and even early washing machines.

These amazing inventions, especially in travel and communication, helped Great Britain become the world's top industrial country and a leader in trade.

The Power of Railways

After 1830, a new system of railways changed everything. Historians David Brandon and Alan Brooke said that railways created our modern world.

Railways needed lots of building materials, coal, iron, and steel. They were great at moving coal, which powered factories and heated homes. Millions of people could travel for the first time. Mail, newspapers, and books could be sent easily and cheaply, spreading ideas faster than ever.

They also helped improve people's diets. A smaller number of farmers could feed many more people living in cities. Railways created many jobs, both directly and indirectly. They helped Britain become the "Workshop of the World" by making it cheaper to move raw materials and finished goods, many of which were sold to other countries.

By the late 1800s, almost everyone in Britain was affected by the railways. They helped change Britain from a farming country to one where most people lived in cities.

Britain's "Golden Years"

The middle of the Victorian era (from 1850 to 1870) is often called Britain's "Golden Years." The country's income per person grew by half! This growth came from more factories, especially those making textiles (like cloth) and machines. Britain also made a lot of money from its worldwide trade network. British business owners even built railways in other countries.

There was peace abroad, except for the short Crimean War (1854–56), and peace at home. People felt free, and taxes were very low. The government didn't control much.

Working-class people started joining trade unions and cooperative societies to improve their lives. Companies often looked after their workers, providing housing, schools, and even libraries. Middle-class people tried to help the working classes live more "respectable" lives, like their own.

Historian Llewellyn Woodward said that England in 1879 was a better country than in 1815. Life was fairer for the weak, for women and children, and for the poor. People had more opportunities and felt less stuck in their lives. However, he also noted that housing and living conditions for many working-class people were still very bad.

The First Cooperatives

In December 1844, a group called the Rochdale Society of Equitable Pioneers started what is seen as the world's first cooperative. Twenty-eight members, many of them weavers, joined together. They opened a store that they owned and managed democratically. This allowed them to buy food items they couldn't afford otherwise.

Within ten years, the British cooperative movement grew to nearly 1,000 cooperatives. This idea also spread worldwide, with the first cooperative bank starting in Germany in 1850.

Housing in Victorian Cities

Cities grew very quickly in the 1800s, especially new factory towns and big service centers like London. Many people moved in so fast that there wasn't enough good housing for everyone. So, new people with low incomes often ended up living in very crowded slums.

Clean water, proper sewers, and public health services were not good enough. This led to high death rates, especially for babies. Diseases like tuberculosis, cholera (from dirty water), and typhoid were common.

Poverty and Living Conditions

Britain's population grew a lot in the 1800s, and more and more people moved to cities because of the Industrial Revolution. Wages slowly got better. By 1901, real wages (how much people could buy with their money) were 65 percent higher than in 1871. Many people saved their money. The number of people with savings accounts grew from 430,000 in 1831 to 5.2 million in 1887.

However, people moved into industrial areas and cities faster than new homes could be built. This caused overcrowding and problems with clean water and sewage systems.

These problems were even worse in London, where the population grew incredibly fast. Large houses were divided into many small apartments, and landlords often didn't keep them in good repair. This created terrible slum housing. One writer, Kellow Chesney, described how "thirty or more people of all ages may inhabit a single room."

The laws for helping the poor, called the English Poor Laws, changed a lot. Many workhouses (or poorhouses) were built, where poor people could live and work in exchange for food and shelter.

Child Labour

In the early Victorian era, before reforms in the 1840s, it was common for young children to work in factories, mines, and as chimney sweeps. Child labour was a big part of the Industrial Revolution. For example, the famous writer Charles Dickens worked in a factory at age 12 because his family was in a debtors' prison.

Reformers wanted children to go to school. In 1840, only about 20 percent of children in London went to school. By the 1850s, about half of the children in England and Wales were in school. From the 1833 Factory Act, there were attempts to make child workers go to school part-time, but this was hard to make happen. It wasn't until the 1870s and 1880s that children were truly required to go to school.

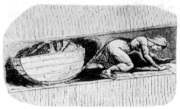

Children from poor families were expected to help earn money for their families. They often worked long hours in dangerous jobs for very little pay. Small, agile boys were used by chimney sweeps to climb inside chimneys. Tiny children were sent under machines in factories to pick up cotton bobbins. Children also worked in coal mines, crawling through narrow tunnels that adults couldn't fit into.

Other children worked as errand boys, cleaned streets, shined shoes, or sold small items like matches and flowers. Some children became apprentices to learn trades like building, or worked as domestic servants. There were over 120,000 domestic servants in London in the mid-1800s. Working hours were very long. Builders might work 64 hours a week in summer, and domestic servants were often on duty for 80 hours a week.

One 12-year-old girl named Isabella Read, who carried coal in a mine in 1842, described her work: "I am wrought with sister and brother, it is very sore work... I carry about 1 cwt. and a quarter on my back; have to stoop much and creep through water, which is frequently up to the calves of my legs."

As early as 1802 and 1819, laws called Factory Acts were passed to limit children's working hours in factories to 12 hours a day. These laws didn't work very well. After protests, a Royal Commission in 1833 suggested that children aged 11–18 should work a maximum of 12 hours a day. Children aged 9–11 should work no more than eight hours, and children under nine should not be allowed to work at all. However, this law only applied to the textile industry.

More protests led to another law in 1847 that limited both adults and children to 10-hour working days. The Mines Act of 1842 was a big step, banning women and children from working underground in coal, iron, lead, and tin mines.

|