Edith Anne Stoney facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edith Anne Stoney

|

|

|---|---|

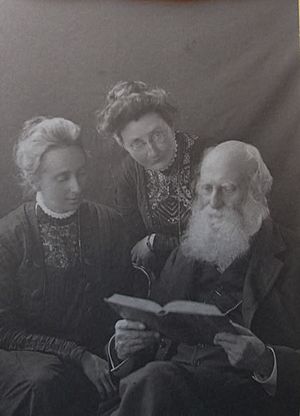

Edith Anne Stoney c. early 1890s

|

|

| Born | 6 January 1869 Dublin, Ireland

|

| Died | 25 June 1938 (aged 69) Bournemouth, England

|

| Alma mater | |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Medical Physics |

| Institutions |

|

Edith Anne Stoney (born January 6, 1869 – died June 25, 1938) was an amazing physicist from Dublin, Ireland. She came from a well-known family of scientists. Many people believe she was the very first woman to work as a medical physicist. This means she used physics to help with medicine and healthcare.

Contents

Early Life and Family

Edith Stoney was born in Dublin. Her father, George Johnstone Stoney, was a famous physicist. He even came up with the word "electron" in 1891!

Edith had two brothers and two sisters. Her brother, George Gerald, was also a Fellow of the Royal Society, like their father. Her sister, Florence Stoney, became a radiologist (a doctor who uses X-rays). She even received an award called the OBE.

Edith's family was full of smart people! Her cousin, George Francis FitzGerald, was also a physicist. Her uncle, Bindon Blood Stoney, was an engineer who built many bridges in Dublin.

Education and Early Career

Edith was very good at math. She won a scholarship to Newnham College, Cambridge. In 1893, she did very well in her exams. However, women were not allowed to get degrees from Cambridge until 1948.

Later, she earned her BA and MA degrees from Trinity College, Dublin. This happened after the college started accepting women in 1904. While at Newnham, she was in charge of the college's telescope.

After college, Edith worked briefly on gas turbine calculations. She also helped design searchlights. Then, she became a math teacher at the Cheltenham Ladies’ College.

Working in London: Medical Physics Pioneer

In 1876, a new law made it illegal to stop people from studying medicine because of their gender. This led to the creation of the first medical school for women in Britain. It was called the London School of Medicine for Women.

Edith's sister, Florence, studied medicine there and became a doctor. In 1899, Edith became a physics lecturer at the school. Her job was to set up a physics lab and create the physics course.

She designed the lab for 20 students. The course covered pure physics topics like mechanics, magnetism, electricity, and optics. One of her former students remembered her lectures as informal talks. Edith would draw on the blackboard and often ask, "Have you taken my point?"

In 1901, Florence became a "medical electrician" at the Royal Free Hospital. The next year, the two sisters opened a new x-ray service there. This was a big step in using physics for medicine!

Supporting Women's Rights

While working at the school, Edith and Florence also supported the women's suffrage movement. This movement fought for women's right to vote. They did not support violent actions, though.

Edith also played a key role in the British Federation of University Women (BFUW). She was the treasurer from 1909 to 1915. She worked to help women become lawyers and parliamentary agents. A law allowing this was passed after the war.

Edith left her job at the school in March 1915.

World War I: A Hero on the Front Lines

When World War I began, Edith and Florence offered to help the British Red Cross. They wanted to provide X-ray services for soldiers in Europe. But their offer was refused because they were women.

Florence then set up her own unit and went to Europe. Edith stayed in London, organizing supplies.

Edith then joined the Scottish Women's Hospitals for Foreign Service (SWH). This group was formed by the women's suffrage movement to provide medical help during the war.

X-ray Work in France

The SWH set up a 250-bed hospital in France. Edith's job was to plan and run the x-ray facilities. She used X-rays to find bullets and shrapnel in soldiers. She also used them to diagnose gas gangrene, a serious infection. If a soldier had gas gangrene, an immediate amputation was often needed to save their life.

The hospital was close to the front lines. Edith said that by September 1915, "the town had been evacuated, the station had been mined, and we heard the heavy guns ever going at night time." The unit was made up entirely of women, except for two male drivers and her assistant.

Moving to Serbia

Later, Edith and her team were sent to Serbia. They traveled by ship and train to Ghevgheli (now Gevgelija in North Macedonia). They set up a hospital in an old silk factory. They treated many soldiers with injuries like frostbite and severe wounds.

After some defeats, Edith and her staff had to retreat to Salonika (now Thessaloniki in Greece). They quickly set up another hospital by the sea. By New Year's Day 1917, Edith had the lights and X-rays working again!

Even with limited equipment, she set up a department for electrotherapy. This helped soldiers with muscle rehabilitation. She also helped fix X-ray systems on two British hospital ships.

Edith returned to France in October 1917. She led the X-ray departments at other SWH hospitals. In March 1918, she had to supervise another retreat when German troops advanced.

During the final months of the war, the fighting got worse. Edith's workload increased greatly. In June alone, they did over 1,300 X-ray procedures.

Awards and Recognition

Edith's brave service during the war was recognized by several countries. She received:

- The "Médaille des épidémies du ministère de la Guerre" and the Croix de Guerre from France.

- The Order of St Sava from Serbia.

- The Victory and British War Medals from Britain.

After the War and Retirement

After the war, Edith became a physics lecturer at King's College for Women. She worked there until she retired in 1925.

She then moved to Bournemouth to live with her sister Florence. Florence was ill with spinal cancer and passed away in 1932.

Continued Work and Legacy

Even in retirement, Edith stayed busy. She continued her work with the BFUW. She also became an early member of the Women's Engineering Society. She traveled a lot and spoke about women in engineering. In 1934, she spoke to the Australian Federation of University Women. She highlighted how much women workers helped during the war.

In 1936, Edith created a special scholarship called the Johnstone and Florence Stoney Studentship. This scholarship helps young women graduates do research overseas. It also helps physicists go to medical school. This fund is now managed by Newnham College, Cambridge.

Edith Stoney passed away on June 25, 1938, at the age of 69. Many scientific and medical journals, as well as newspapers, wrote about her amazing life.

Legacy

Edith Stoney is remembered for her great bravery and cleverness during the war. She found creative ways to provide medical care in very difficult situations. She strongly believed in education for women. She helped many young women pursue research and medical careers. Through all her work, Edith Stoney is known as a true pioneer in medical physics.

| Claudette Colvin |

| Myrlie Evers-Williams |

| Alberta Odell Jones |