Edward Millen facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Edward Millen

|

|

|---|---|

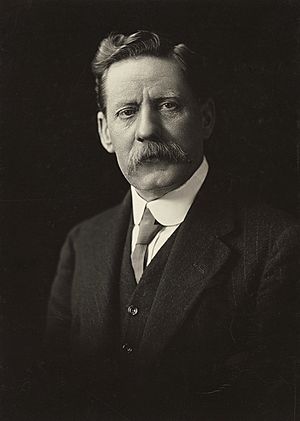

Millen in the 1910s

|

|

| Vice-President of the Executive Council | |

| In office 2 June 1909 – 29 April 1910 |

|

| Preceded by | Gregor McGregor |

| Succeeded by | Gregor McGregor |

| In office 17 February 1917 – 16 November 1917 |

|

| Preceded by | William Spence |

| Succeeded by | Littleton Groom |

| Minister for Defence | |

| In office 24 June 1913 – 17 September 1914 |

|

| Preceded by | George Pearce |

| Succeeded by | George Pearce |

| Minister for Repatriation | |

| In office 28 September 1917 – 9 February 1923 |

|

| Preceded by | New title |

| Succeeded by | Title abolished |

| Senator for New South Wales | |

| In office 29 March 1901 – 14 September 1923 |

|

| Succeeded by | Walter Massy-Greene |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 7 November 1860 Deal, Kent, England |

| Died | 14 September 1923 (aged 62) Caulfield, Victoria |

| Nationality | English Australian |

| Political party | Free Trade (1894–1906) Anti-Socialist (1906–09) Liberal (1909–17) Nationalist (1917–23) |

| Spouse | Constance Evelyn Flanagan |

| Occupation | Journalist |

Edward Davis Millen (born 7 November 1860 – died 14 September 1923) was an important Australian journalist and politician. He is best known as Australia's very first Minister for Repatriation. This role meant he helped soldiers returning from war.

Millen moved to Australia from England around 1880. He became a journalist and later entered politics. He served in the New South Wales state parliament from 1894 to 1898. Even though he supported the idea of Australia becoming one country, he strongly disagreed with some of the early plans for it.

He became a member of the Australian Senate in 1901. This was at Australia's first federal election. He led the main conservative political groups in the Senate for many years. He was also a minister in several governments, including Minister for Defence during the start of World War I.

His most important job was as the first Minister for Repatriation from 1917 to 1923. In this role, he helped set up a new government department. This department was created to support soldiers returning home after the war. He even briefly acted as Prime Minister in 1919. He worked very hard, and his health suffered because of it. He passed away in 1923.

Contents

Early Life and Moving to Australia

Edward Millen was born in Deal, Kent, England, in 1860. His father, John Bullock Millen, was a pilot for ships. Edward went to school in England and worked in marine insurance.

In 1880, when he was about 20 years old, he moved to New South Wales, Australia. On 19 February 1883, he married Constance Evelyn Flanagan. They lived as graziers, which means they raised livestock, in Brewarrina.

Millen also worked as a journalist. He wrote for newspapers in places like Bourke and Walgett. He even became part-owner and editor of the Western Herald and Darling River Advocate. He also worked as a land agent, helping people buy and sell land.

He first tried to become a member of the New South Wales parliament in 1891 but lost. He tried again in 1894 and won. He became known for wanting to change land laws. He pushed for better support for farmers, especially during droughts.

Starting in State Politics

In 1893, Edward Millen helped start the New South Wales Australasian Federation League. This group wanted to unite the six Australian colonies into one country, called the Commonwealth of Australia.

However, Millen had some concerns about how this new country would be set up. He didn't like the idea of all states having the same number of representatives in the Australian Senate. He thought this was "objectionable and dangerous" for larger states like New South Wales. Because of his concerns, he opposed the first vote on Federation in 1898.

Despite his early opposition, Millen was appointed to the New South Wales Legislative Council in 1899. This helped make sure the laws for the 1899 Federation vote would pass. At the first federal election in March 1901, Millen was elected to the Australian Senate for New South Wales. He was a member of the Free Trade Party.

His Time in the Senate

Millen quickly became an important leader in the Senate. He was a strong supporter of "free trade." This meant he believed in fewer taxes on goods coming into the country. He thought this would help businesses grow.

He also strongly supported the White Australia policy. This policy aimed to control who could immigrate to Australia. Millen believed that allowing certain groups of workers into Australia would lower wages for everyone.

In 1907, Millen became the leader of the Free Trade Party in the Senate. Later, in 1909, he became the Leader of the Government in the Senate. He also served as Vice-President of the Executive Council under Prime Minister Alfred Deakin. He continued to lead conservative political groups in the Senate until he died.

In 1913, Millen became Minister for Defence. He held this job when World War I began in 1914. He helped organize the first group of 20,000 soldiers for the Australian Imperial Force. He also set up the first defence plans for the war.

After the Labor Party won the 1914 election, Millen went back to leading the Opposition in the Senate. However, he still played a role in the war effort by joining the parliamentary war committee.

Minister for Repatriation

In 1917, Edward Millen joined Billy Hughes's government. He became Australia's first Minister for Repatriation. This was a very important job. It meant he was in charge of helping soldiers who were returning home from World War I.

Millen and Major Nicholas Lockyer were responsible for creating a brand new government department. This department was set up to help veterans. Many of the staff were returned soldiers themselves. They didn't have much experience in government work, which sometimes caused problems.

Millen helped pass the War Service Homes Act 1918–19. This law created the War Service Homes Commission. This commission helped soldiers get homes after the war.

In mid-1919, when Prime Minister Billy Hughes was away in Europe, Millen briefly served as acting Prime Minister. During this time, he helped solve a big strike by seamen.

In 1920, Millen went to Geneva to represent Australia at the first meeting of the League of Nations. This was an international organization created to promote peace after the war. He helped Australia gain control over some Pacific islands.

Millen's heavy workload began to affect his health. He thought about retiring but decided to keep working. He was re-elected to the Senate in 1922. However, his health continued to get worse. He retired from his ministerial role in February 1923.

Edward Millen passed away on 14 September 1923, at the age of 63. He died from a kidney disease. He was survived by his wife and two daughters. He was given a state funeral, which is a special ceremony for important public figures.

His Legacy

Edward Millen faced a lot of criticism during his time as Minister for Repatriation. However, he is remembered as a very important person in Australia's efforts to help its soldiers after the war. Many people believe he was the most important person in developing how Australia supported its veterans.

After he died, Billy Hughes said that Millen was unmatched as a leader in the Senate. George Pearce, another politician, remembered him as one of the smartest and most critical thinkers in the Australian Parliament.

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |