Etna Iron Works facts for kids

The former Etna Iron Works after being rented by the Edison Machine Works in about 1881

|

|

| Defunct (1881) | |

| Industry | Manufacturing |

| Founded | 1852 |

| Headquarters |

,

United States

|

| Products | Marine steam engines, machine tools, iron products |

| Total assets | $150,000 (1860s) |

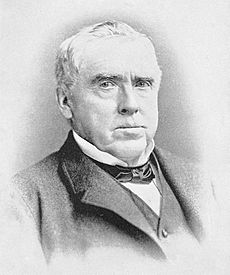

| Owner | John Roach |

|

Number of employees

|

2,000 (1860s) |

The Etna Iron Works was a big factory in New York City during the 1800s. It made many things from iron, especially powerful engines for ships. When John Roach, a skilled iron worker, bought it with three friends in 1852, it was a small business that wasn't doing well. But John Roach soon took full control. He quickly turned the Etna Works into a very successful company that made all sorts of iron products.

John Roach used the time of the American Civil War to make the Etna Works one of New York's top builders of ship engines. After the war, he bought out many of his rivals who were having money problems. He then moved his main operations to another factory called the Morgan Iron Works. Later, the Etna Works building was rented to the famous inventor Thomas Edison. Edison used it to build dynamos, which are machines that make electricity. The Roach family sold the old Etna Works property in 1887. The buildings were later taken down when the city rebuilt the area.

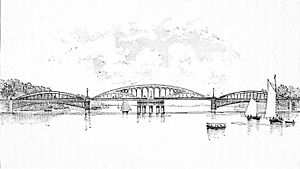

The Etna Iron Works had some cool achievements. In the 1860s, they built the steam-powered Third Avenue Harlem Bridge. They also made the engines for the huge iron warship USS Dunderberg. Plus, they built the engines for the passenger ships Bristol and Providence. These were the biggest ship engines ever built in the United States at that time!

Contents

Starting the Business

John Roach came to the United States from Ireland in 1832 when he was 16. He started working as a simple laborer, earning only 25 cents a day. He learned how to work with iron and became an expert at making marine steam engines. John worked for another company for 20 years, learning a lot about the business.

By the 1850s, John had a growing family and wanted a more secure future. He decided to start his own business. He only had $1,000 saved. But he convinced three co-workers to join him. One of them, his brother-in-law Joseph Johnstone, had $8,000. Together, the four partners gathered $10,000 to start their company.

In April 1852, John Roach and his partners bought the Etna Iron Works. It was a small factory in New York that was struggling. They paid $4,700 for it. The factory was located at 102 Goerck Street. It had a small foundry, which is a place for casting metal, and some raw materials.

Early Success and Growth

After buying the factory, John Roach was in charge of finding new customers. His partners managed the daily work. John's first sale was for cast grate bars for a distillery.

After their first year, the partners made a small profit of $1,000. John wanted to use this money to make the business bigger. But his partners wanted to split the money, each taking $250. John realized they had different goals. So, he took out a loan and bought his partners' shares. This made him the sole owner of the Etna Iron Works.

John then started looking for work from local shipyards. Even though most ships were still made of wood, they needed a lot of iron parts. John made a profit of $8,000 from these sales in just three months. This gave his business a strong start.

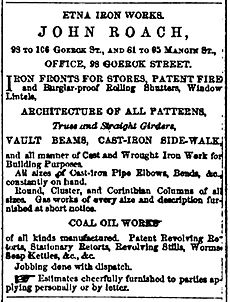

John kept expanding the business by selling many different products. These included Franklin stoves, firebacks, and parts for iron shutters. In 1856, he added a new steam boiler to the factory. This boiler helped melt iron faster, saving time and money. He also bought the building next door. He used the top floor as a pattern shop and rented out the other floors.

By 1859, the Etna Iron Works had 40 employees. The factory was worth $15,000. People at the time said John was "getting along well" and was trustworthy for credit.

Factory Accident

On September 2, 1859, a boiler at the Etna Works exploded. It had accidentally run dry. One man died, and two others were badly hurt. The building where the boiler was located was destroyed. The damage cost $5,000, but insurance covered it. The factory couldn't work without steam power.

But John Roach didn't give up. He quickly arranged to use a boiler from a nearby factory. He ran a 200-foot pipe to connect it to his workshop. The Etna Works was back in business within 48 hours!

A Helping Hand

In 1859, John Roach's close friend, a lawyer named John Baker, passed away. Baker left John Roach in charge of his estate, which was worth $70,000. John was to invest this money until Baker's four children grew up. Since the money couldn't be claimed until 1881, it was like a long-term, interest-free loan for John. He soon used it to expand his business even more.

Building a Bridge

One of the biggest projects for the Etna Iron Works was building the Third Avenue Harlem Bridge. This bridge crossed the Harlem River in New York. The city asked companies to bid on the project in 1860. John Roach won the contract because he offered the lowest price. The bridge needed a middle section that could turn to let large ships pass.

John had never built a bridge before. So, he hired an experienced engineer to design and oversee the project. He also hired other companies for the stone work. The bridge ended up being 526 feet long. It had stone foundations and an iron structure. The middle part was 216 feet long and turned using steam power. The bridge opened in 1868. It worked well for about 30 years before a new, bigger bridge was built.

The Civil War Years

John Roach had always wanted to build ship engines, just like his old mentor. It was a tough business to get into because it cost a lot of money. But John believed he could succeed by using the best tools and methods. In the late 1850s, he sent engineers to the United Kingdom to learn about the newest engine technology. He even worked as a mechanic for other engine builders in New York to learn their secrets!

When the American Civil War began in 1861, John Roach was ready. There was a huge demand for ship engines because of the war. He first contacted William H. Webb, a shipbuilder who had a contract for a massive new ironclad called USS Dunderberg. Webb's usual engine suppliers were too busy. Webb was so happy to find John Roach that he gave him the Dunderberg engine contract. He also helped John get the money he needed to upgrade his factory for the job.

Next, John went to Washington to meet with the U.S. Navy's Chief Engineer. On October 24, 1862, the Navy gave John a contract to build machinery for a new gunboat, Peoria. This was the first of many such contracts for the Navy. John also got contracts for engines for two new merchant ships, Electra and Galatea.

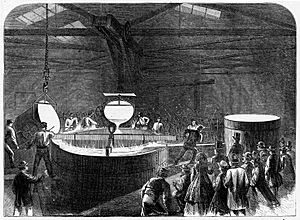

With these contracts, John began to prepare the Etna Iron Works for its new role. He hired Thomas Main, a top engineer, to be the factory's superintendent. John then reorganized the factory. He added new shops for boilers, machines, copper work, and blacksmithing. He also bought many new machines, like cranes, planers, and lathes. Some of this new equipment was huge, like a machine that could finish 100-ton iron plates. Another machine could bore a 112-inch cylinder, making them the two largest machine tools in the country!

Over the next two years, John's factory made engines for at least 15 ships. This included more orders from the U.S. Navy. At its busiest during the war, the Etna Iron Works had almost 2,000 workers. It was valued at $150,000, making it one of New York's most important engine builders.

After the War

After the war, the U.S. Navy sold off hundreds of ships. This flooded the market and caused ship prices to drop a lot. Many old American shipyards and engine builders went out of business. New York's shipping industry was hit very hard. By 1867, most of John Roach's competitors had gone bankrupt.

But John Roach managed to do well. He got many different contracts for machinery. The Navy ordered engines and boilers for some new ships. Shipbuilder William Webb hired John to build machinery for two large new sidewheel steamers, Bristol and Providence. The engines for these two ships were massive, with 110-inch cylinders. They were the largest ship engines ever made in the United States at that time! Even more important for John, he realized the government planned to modernize its shipyards. So, he started making machine tools in 1866. He won almost a million dollars in government contracts for machine tools between 1866 and 1868.

At this point, John decided his business had outgrown its location. He wanted a factory right on the water. This would save him money on transporting engines to the docks. It would also let him get into the profitable business of repairing ships. The perfect place was the Morgan Iron Works. It was a top factory with access to the East River. Like many other ship engine factories, it had been mostly empty since the Civil War. Luckily for John, the owner, Charles Morgan, needed money. Morgan quickly agreed to sell the factory and all its equipment for $450,000.

Around the same time, two of John's old competitors went bankrupt. John bought their best equipment at very low prices. He also hired their best workers. He combined the best workers and equipment from the Etna and Morgan factories. He moved all his operations to the Morgan Iron Works, leaving his old factory on Goerck Street. John also made money by selling his extra equipment to the U.S. Navy.

What Happened Next

After moving his main business to the Morgan Iron Works, John Roach rented out his old Etna Iron Works property. It continued to operate as a general ironworks under new management until about 1881. That's when the inventor Thomas Edison moved his electrical company there. Edison renamed the factory the Edison Machine Works. He used it to build DC dynamos (machines that make direct current electricity) until 1887. In that year, the Roach family sold the property. Edison's company had moved to a much bigger site in Schenectady, NY. The Etna Works buildings were later removed in the 1940s as part of a city redevelopment project.

John Roach himself went on to build his own shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania. It was called the Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works. From 1871 to the mid-1880s, it became America's largest and most productive shipyard.

Images for kids

| Leon Lynch |

| Milton P. Webster |

| Ferdinand Smith |