Morgan Iron Works facts for kids

|

|

| Private | |

| Industry | Manufacturing |

| Fate | Sold |

| Predecessor | T. F. Secor & Co. |

| Founded | 1838 |

| Founders |

|

| Defunct | 1907 |

| Headquarters |

New York

,

United States

|

|

Area served

|

United States |

|

Key people

|

T. F. Secor, Charles Morgan, George W. Quintard; later John Roach and his sons John Baker and Stephen Roach |

| Products | Marine steam engines |

| Services | Ship repair |

| Total assets | $450,000 (1867) |

| Owner |

|

|

Number of employees

|

1,000 (1865) |

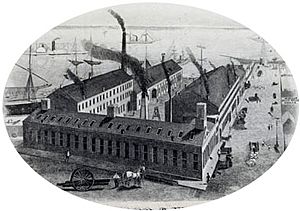

The Morgan Iron Works was a very important factory in New York City during the 1800s. It made powerful marine steam engines for ships. The company started in 1838 as T. F. Secor & Co. Later, one of its first investors, Charles Morgan, took over and changed its name to Morgan Iron Works.

This factory was a top producer of ship engines for many years. Between 1838 and 1867, it built at least 144 engines. This included 23 engines for U.S. Navy ships during the American Civil War.

In 1867, the Morgan Iron Works was sold to a shipbuilder named John Roach. He combined its work with his own shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania. The factory kept making engines and repairing ships under Roach and his son, John Baker Roach. It finally closed in 1907 when the Roach family left the shipbuilding business.

Contents

Early Years: Secor & Co. (1838–1850)

The T. F. Secor and Co. factory began in New York City in 1838. It was located on Ninth Street near the East River. Three partners owned the factory at first. They were T. F. Secor, William K. Caulkin, and the rising businessman Charles Morgan. Each owned one-third of the new company.

In 1845, the U.S. Congress made new laws to help American shipping companies. These laws included money to help them compete with British companies. This led to more demand for steamships in the U.S. Charles Morgan then sold his shares in sailing ships. He invested that money into the Secor factory instead.

The factory grew bigger, covering one and a half city blocks. It stretched between Eighth and Tenth Streets. By this time, about 700 people worked there. They built engines for ships that sailed along the coast and across oceans.

Morgan and Quintard Take Over (1850–1867)

In 1847, Charles Morgan put his son-in-law, George W. Quintard, in charge of money matters at Secor & Co. Quintard was a great manager and quickly moved up in the company. In February 1850, Morgan bought out the other partners. He then renamed the company the Morgan Iron Works.

Quintard became the new manager of the factory. He stayed in this job until the company was sold to John Roach in 1867. Morgan, as the only owner, provided all the money and credit for the business.

There was a small change between 1857 and 1861. Morgan's other son-in-law, Charles A. Whitney, joined as a co-manager. During this time, Morgan sold the factory to Quintard and Whitney for $250,000. Whitney got one-third of the company, and Quintard got the rest. They took out a $67,000 loan to help run the business. When Whitney left, Morgan bought the business back for the same price. He also paid off the loan himself.

Factory Improvements in the 1850s

After Morgan took over in 1850, Quintard started a big improvement plan for the factory. He added new, heavy machines like steam hammers. He also built a floating steam derrick and a new dockyard on the East River. Quintard also started making different products. These included machines for Cuban sugar mills and large pumps for a water company in Chicago.

By this time, Charles Morgan's shipping business was growing fast. He became the factory's main customer. In 1850, Morgan ordered two large steamers, the San Francisco and the Brother Jonathan. Both were built for his Empire City Line. In 1852, he ordered five more ships to replace older ones. These included Texas, Louisiana, Mexico, Perseverance, and Meteor. All of them had engines built by the Morgan Iron Works.

Morgan also lost four of his ships in accidents around this time. They were the Palmetto, Globe, Galveston, and the new Meteor. The total value was $250,000. Morgan usually insured his own ships, so he didn't get money back for these losses. But he was rich enough to handle it. In the next two years, he had four more ships built. These were the Charles Morgan, Nautilus, Orizaba, and Tennessee. All but one of these also got their engines from Morgan Iron Works.

The Morgan Iron Works won its first contract for the Navy on October 28, 1858. It was to build an engine for a steam sloop-of-war, the USS Seminole. Some politicians complained that the company got special treatment. But in a later investigation, Quintard explained that the factory had tried for many Navy contracts before and never won. The investigation found no wrongdoing.

By the end of the 1850s, Morgan Works was a top maker of marine steam engines in America. They specialized in engines for coastal and river ships. From 1850 to 1860, the factory built engines for 49 ships. Their engines were used by American steamship companies as far away as China.

The American Civil War (1861–1865)

The American Civil War started badly for Charles Morgan. The Confederacy seized all his ships in the Gulf of Mexico. But Morgan managed to recover and make a lot of money from the war. This was mostly thanks to the Morgan Iron Works.

The war created a huge need for new ships. Shipyards and engine makers saw a big increase in business. The Morgan Iron Works took full advantage of this demand. During the war, they built engines for 38 ships. This included 23 merchant ships and 13 warships for the U.S. Navy. The factory even built an engine for an Italian Navy warship, the Re Don Luige de Portogallo.

U.S. Navy warships with Morgan Iron Works engines included USS Ticonderoga, USS Ascutney, USS Wachusett, and the fast warship USS Ammonoosuc. The factory also agreed to build the entire monitor USS Onondaga. However, another company built the ship's body.

By the end of the war, the Morgan Works had earned over $2.2 million from its Navy contracts alone. Morgan also made more money by ordering ships from Harlan & Hollingsworth. He then sold or rented these ships to the U.S. Navy.

Selling to John Roach (1867)

After the war, the U.S. government sold hundreds of ships it had used during the conflict. They sold them at very low prices. This made it hard for U.S. shipyards and engine builders to find work. Many marine engine companies in New York went out of business after the war. Only two important ones remained: the Morgan Iron Works and the Etna Iron Works of John Roach.

John Roach was able to keep making money after the war. He started making machine tools and selling them to the U.S. Navy. The Navy was upgrading its shipyards at the time. The Morgan Iron Works, however, struggled. It built only two engines in the two years after the war. It stayed open only because Morgan could afford to lose money. In 1866, Morgan had another financial problem. His new shipping lines to Mexico failed when Maximilian I of Mexico was overthrown.

Meanwhile, John Roach wanted to add shipbuilding to his engine business. He saw the Morgan Iron Works, with its dockyard on the East River, as a perfect step. When he offered to buy the Morgan Works in 1867, Morgan was ready to sell. They agreed on a price of $450,000. Roach paid $100,000 in cash and agreed to two loans for the rest. Roach later had his own money problems and didn't pay the loans on time. But Morgan chose not to take the factory back. Roach paid off the debts shortly before Morgan died in 1878.

Roach Family Takes Over (1867–1907)

By buying the Morgan Iron Works and other companies, John Roach almost had a monopoly on ship and engine building in New York. He then closed his Etna Iron Works. He moved the best workers and equipment from Etna and other old companies to his new East River factory. This made the Morgan Works America's best maker of marine steam engines.

In 1871, Roach bought a shipyard in Chester, Pennsylvania, that had failed. He updated it completely and renamed it the Delaware River Iron Ship Building and Engine Works. This became America's largest and busiest shipyard until the mid-1880s. Even though the Chester shipyard had its own engine plant, Roach kept the Morgan Iron Works. He used it to build engines for his own ships and for other customers. He also used it for ship repairs and to finish new ships.

Roach even expanded the Morgan Works for its new role. He added people to make ship furniture and made the plumbing department bigger. He could also use the Morgan Works to keep his business running during worker strikes. He would just move his operations from one yard to the other. He kept the name Morgan Iron Works, but it became part of his new main company, John Roach & Son (later John Roach & Sons).

After a difficult political fight over a Navy contract for the USS Dolphin in 1885, Roach retired. He was very sick at the time. His business empire was put under special management to sort out its finances. But after all his debts were paid, his family still owned both the Chester shipyard and the Morgan Iron Works. Roach's oldest living son, John Baker Roach, took over the business. His younger son, Stephen, became the money manager for the Morgan Works.

The brothers continued to run the business much like their father. However, it was no longer the top company it once was. When John Baker Roach died in 1908, the Roach family decided to leave the shipbuilding business. Both the Morgan Iron Works and the Chester shipyard closed. The Morgan Works building was turned into apartments. In 1949, the area where the factory stood was redeveloped into a low-cost housing project, the Jacob Riis Houses, which are still there today.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |