First siege of Zaragoza facts for kids

Quick facts for kids First siege of Zaragoza |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of the Peninsular War | |||||||

Assault on the walls of Saragossa, by January Suchodolski |

|||||||

|

|||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

|

|||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 9,500-15,500 | 13,000 | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 3,500 killed, wounded or captured | 3,000-5,000 killed, wounded or captured | ||||||

The first siege of Zaragoza (also known as Saragossa) was a major battle during the Peninsular War (1807–1814). A French army tried to capture the Spanish city of Zaragoza in the summer of 1808. The French, led by General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes and later General Jean-Antoine Verdier, attacked the city many times. However, the brave Spanish defenders pushed them back each time.

Contents

Why Did the Siege Happen?

The Peninsular War began with many small uprisings in Spain against French rule. At first, Napoleon, the French emperor, thought these were minor issues. He sent small groups of soldiers to stop them.

French Plans for Aragon

In northeastern Spain, a French leader named Marshall Bessières sent General Charles Lefebvre-Desnouettes to stop the rebellion in Aragon. General Lefebvre's group included about 5,000 foot soldiers, 1,000 cavalry (soldiers on horseback), and two groups of cannons. But Lefebvre soon realized the rebellion was much bigger than expected.

Spanish Leaders and Forces

The Spanish side was led by General José de Palafox. He was appointed Captain-General of Aragon in late May. He quickly gathered about 7,500 troops. However, most of these soldiers were new and had little experience. Only about 300 cavalry and a few cannon operators were skilled.

Palafox tried to stop the French from reaching Zaragoza. His older brother, the Marquis of Lazan, tried to fight them at Tudela on June 8, 1808. He tried again at Mallen on June 13, 1808. Palafox then sent 6,000 soldiers, but they were defeated at Alagon on June 14, 1808. Palafox himself was hurt. The remaining Spanish forces then went back to Zaragoza to defend the city.

The Siege of Zaragoza Begins

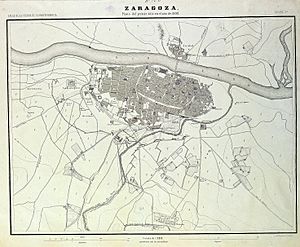

Zaragoza had some natural defenses. It was protected by two old medieval walls and two rivers. The Ebro river was to the northeast, and the Huerva was to the south. The western side of the city was more open to attack. However, the city's real strength was its many strong buildings and narrow streets. These streets were easy to block with barricades, making it hard for attackers to move through.

First French Attack on the City

General Lefebvre reached Zaragoza on June 15, 1808. At this time, the Spanish had more soldiers, about 11,000. But only half of them had battle experience from the defeat at Alagon.

The next day, Lefebvre attacked the western wall of the city. He expected the Spanish to give up quickly. The French broke into the western part of the city. Their allies, Polish troops, broke through the Gate of Carmen. They captured the nearby monastery. Polish cavalry also broke through the Santa Engracia Gate and fought their way into the city center.

However, the French did not support the Polish troops well. The Polish soldiers were ordered to leave the city center and retreat. In this first attack, the French had about 700 soldiers killed or wounded. The Polish troops lost about 50 soldiers.

Palafox Seeks More Troops

General Palafox was not in Zaragoza during this first attack. He had left to gather more troops in Upper Aragon. He planned to attack the French supply lines. Palafox gathered another 5,000 troops. But these new forces were defeated at Épila on June 23–24, 1808. Palafox returned to Zaragoza with only 1,000 extra soldiers.

French Reinforcements Arrive

The French army received more help. General Jean-Antoine Verdier arrived with 3,000 soldiers on June 26, 1808. Since General Verdier was higher in rank than Lefebvre, he took command of all the French troops. More French soldiers and powerful siege cannons kept arriving.

Capturing Monte Torrero

On June 28, 1808, Verdier attacked Monte Torrero. This was a hill on the southern bank of the Huerva river. Monte Torrero was important because it overlooked Zaragoza from the south. It should have been strongly defended, but it was not. The French captured the hill easily. The Spanish commander, Colonel Vincento Falco, was later put on trial by a military court and shot.

With Monte Torrero in their hands, the French could use it to set up their siege cannons. Starting at midnight on June 30, 1808, thirty large cannons, four mortars, and twelve howitzers began firing. They shot at Zaragoza without stopping.

Second Major French Attack

The French launched a second big attack on July 2, 1808. This time, they had twice as many soldiers as in their first attack. Even though Zaragoza's defenses were badly damaged by the constant shelling, the barricades inside the city were still standing. Palafox had returned and was leading the defense.

The French managed to get into the city in several places. But they could not move any further. They were forced to retreat again. This attack became famous because of the story of the Maid of Zaragoza, Agustina Zaragoza. Her boyfriend was a cannon operator at the Portillo Gate. All the soldiers at his cannon were killed before they could fire their last shot. Agustina bravely ran forward, grabbed the burning match from her dead boyfriend's hand, and fired the cannon. The French soldiers were hit by a blast of grapeshot (small metal balls) from close range. Their attack was broken. Palafox said he saw this happen himself. Agustina was made a sub-lieutenant for her bravery.

During this attack on July 2, 1808, the French lost 200 soldiers killed and 300 wounded. Because of these losses, Verdier decided not to make any more direct attacks. He decided to continue the siege. However, he did not have enough soldiers to completely surround the city. This meant the Spanish could still get supplies from the north side of the Ebro river for most of the time.

Fighting for Convents

In the second half of July, the French focused on capturing the Capuchin and Trinitarian convents of San Jose. These buildings were to the west of Zaragoza. By July 24, 1808, the French had captured all of them.

Final French Push and Retreat

On August 4, the French started a very heavy cannon attack. They silenced the Spanish cannons and made several holes in the city walls. At 2 PM, Verdier launched a huge attack with thirteen groups of soldiers. They pushed deep into Zaragoza.

By evening, the French had taken half of the city. But the Spanish fought back hard. They pushed the French out, except for a small group of French soldiers who were surrounded by the Spanish.

By this time, the French had lost about 462 soldiers killed and 1,505 wounded. The Spanish had similar or even higher losses. But they still had more soldiers than the French.

The fighting continued for several days. But the French attack had failed. This meant the siege itself was failing. On July 19, 1808, a French army led by General Dupont was forced to surrender at Bailén. This event made both sides realize the French would have to retreat from Zaragoza. Palafox stopped his attacks, but Verdier responded by firing all the ammunition he couldn't carry away.

Finally, on August 14, 1808, Verdier blew up all the strong points he held and left. One of these strong points was the abbey of Santa Engracia, which was destroyed. This marked the end of the first siege of Zaragoza.

In total, the French had 3,500 soldiers killed, wounded, or captured during the siege. Spanish losses were reported as 2,000 at the time, but a number closer to 5,000 is more likely.

What Happened After the Siege?

The Spanish continued their fight against the French in battles like the Battle of Medina de Rioseco.

Palafox's strong defense made him a national hero. He shared this fame with Agustina Zaragoza and many other ordinary people. Zaragoza would face a second, longer, and more famous siege starting in late December. When it finally fell to the French in 1809, Zaragoza was a city of dead bodies and smoking ruins. Only 12,000 people remained from a population of over 70,000 before the war.

The sieges of Zaragoza are also important in Polish history. Along with other events, they became symbols of how Polish soldiers were sometimes used by Napoleon's France. The Poles had joined France to fight against countries like Prussia, Russia, and Austria, which had taken over parts of Poland years earlier. Having lost their own country, they felt it was wrong to fight nations that were also fighting for their freedom.

Polish General Józef Chłopicki praised Colonel Konopka for not fighting Spanish civilians and for giving up Zaragoza's downtown when the French couldn't secure it. This decision helped end the first siege. Chłopicki, who later led Polish troops during the second siege of Zaragoza, also told his soldiers not to fight Spanish civilians unless they were directly attacked. This upset French commanders. The Poles fought for France because Napoleon promised to help bring Poland back as a country. But in their hearts, they supported the Spanish people. This difficult situation for the Polish Legions has been a topic of many poems and discussions in Polish books since the early 1800s.

See also

In Spanish: Sitio de Zaragoza (1808) para niños

In Spanish: Sitio de Zaragoza (1808) para niños

Further read