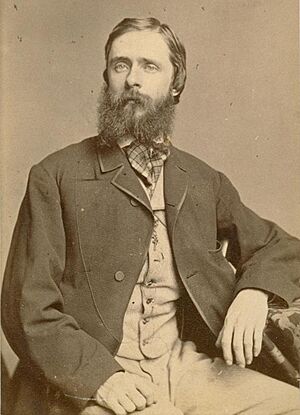

Fitz Hugh Ludlow facts for kids

Fitz Hugh Ludlow (born September 11, 1836 – died September 12, 1870) was an American writer, journalist, and explorer. He wrote about his travels across America, including trips to Yosemite and the forests of California and Oregon, in his book The Heart of the Continent. This book also included his thoughts on the early Mormon settlement in Utah.

Ludlow also wrote many short stories, essays, and articles about science and art. He passed away at the age of 34.

Contents

Early Life

Fitz Hugh Ludlow was born in New York City on September 11, 1836. His father, Henry G. Ludlow, was a minister who strongly supported the abolitionist movement, which worked to end slavery. This was a brave stance at a time when anti-slavery ideas were not always popular, even in northern cities.

His father was also involved with the Underground Railroad, a secret network that helped enslaved people escape to freedom. When Fitz Hugh was a young boy, he misunderstood the term "Underground Railroad" and thought it was a real train underground!

Fitz Hugh's mother, Abigail Woolsey Wells, passed away when he was twelve years old. Her struggles with health may have influenced his thoughts on life and the human spirit.

College Years

Ludlow started his studies at the College of New Jersey, which is now Princeton University, in 1854. He joined a literary and debating club there. After a fire damaged the main building, he moved to Union College. At Union, he joined the Kappa Alpha Society, a social club.

He also took classes in medicine at Union. A very important class for Ludlow was taught by the college president, Eliphet Nott. This class focused on philosophy and writing. Nott was very impressed with Ludlow's writing talent.

In fact, President Nott asked Ludlow to write a song for the graduation ceremony in 1856. Ludlow wrote the lyrics to the tune of an old drinking song. This song, called Song to Old Union, became the school's official song and is still sung at graduations today! Ludlow wrote several popular college songs during his time there.

Becoming a Writer in New York

When Ludlow was twenty-one, his autobiographical book The ... Eater was published. The book was very successful and was printed many times. Even though he published it anonymously at first, Ludlow became well-known because of it.

He briefly studied law and passed the bar exam in New York in 1859. However, he decided not to become a lawyer and instead chose to focus on his writing career.

The late 1850s were an exciting time for writers in New York City. Older magazines were closing, and new ones like the Atlantic Monthly and Vanity Fair were starting up. Ludlow became an editor at Vanity Fair. Through his work, he became part of the lively literary scene in New York, where he met famous writers like Walt Whitman.

Ludlow loved New York City because it was a place where many different kinds of people lived and shared ideas. He wrote that it was like a "bath of other souls" where people could influence each other. New York was also very accepting of unique individuals.

Ludlow wrote for many different publications, including Harper's magazines, the New York World, and the Atlantic Monthly. George William Curtis, an editor at Harper's New Monthly Magazine, described Ludlow as a "slight, bright-eyed, alert young man" who seemed like a boy, even though he was already a successful writer.

Rosalie

Ludlow's fictional stories often included events from his own life. He married Rosalie Osborne in 1859. She was eighteen at the time.

The couple traveled to Florida for the first half of 1859. Ludlow wrote a series of articles called "Due South Sketches" about his experiences there. He described Florida as having a wonderful climate and beautiful scenery. After Florida, they moved back to New York City and became very active in the literary social scene.

The Heart of the Continent

In 1863, Albert Bierstadt was a very famous landscape artist in America. Ludlow admired Bierstadt's paintings and often praised them in his role as an art critic for the New York Evening Post.

Bierstadt wanted to go back West to find new scenes for his paintings, and he asked Ludlow to come with him. Ludlow wrote about their journey in articles for newspapers and magazines, which were later collected into a book. These writings helped make Bierstadt even more famous as an artist who captured the beauty of the American West.

During their journey, they stopped in Salt Lake City, Utah. Ludlow was surprised to find the settlers there to be hardworking and sincere. He had arrived with some negative ideas about the Mormons, but his opinions changed as he met them. He wrote about his impressions, which were read with great interest back East, especially during the American Civil War. Many people in the East saw Utah as a rebellious place, similar to the Southern states. Ludlow's observations became an important part of his book about his travels.

Ludlow wrote that the Mormon community was very organized and strong. He also spent time with Orrin Porter Rockwell, a well-known figure in Salt Lake City. Ludlow wrote a description of Rockwell that is still considered one of the best by those who met him.

Ludlow believed that the Mormons were very sincere in their beliefs, even if others disagreed with them. He saw their leaders as dedicated and passionate.

San Francisco

While in San Francisco, Ludlow stayed with Thomas Starr King, a young and inspiring preacher.

Ludlow discovered another lively group of writers in San Francisco, centered around a newspaper called The Golden Era. This paper published early works by famous authors like Mark Twain and Bret Harte. Mark Twain was not yet widely known at the time. Ludlow wrote that Mark Twain was a unique and funny writer who didn't imitate anyone else. Twain was pleased by Ludlow's praise and even asked him to look at some of his work.

From San Francisco, Bierstadt and Ludlow traveled to Yosemite and then to Mount Shasta before going into Oregon. In Oregon, Ludlow became very ill with pneumonia, which stopped their journey for about a week.

After Ludlow returned to New York City in late 1864, his marriage ended. Rosalie later married Albert Bierstadt. Ludlow then married Maria O. Milliken.

New York Stories

Fitz Hugh Ludlow was a very versatile writer. He wrote stories for magazines, poetry, political comments, and reviews of art, music, and drama. He also wrote about science and medicine. As a newspaper writer, he even translated articles from foreign newspapers.

Most of his stories were light-hearted romances, often featuring funny characters and silly problems that the main character had to overcome to be with a beautiful young woman.

Final Years

In June 1870, Ludlow traveled to Europe with his sister Helen, who had always supported him, and his wife Maria, and one of her sons. They stayed in London for about a month and a half before moving to Geneva, Switzerland, because Ludlow's health was getting worse.

He passed away the day after his thirty-fourth birthday.

See also

In Spanish: Fitz Hugh Ludlow para niños

In Spanish: Fitz Hugh Ludlow para niños

- Fitz Hugh Ludlow Memorial Library

| Emma Amos |

| Edward Mitchell Bannister |

| Larry D. Alexander |

| Ernie Barnes |