František Palacký facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

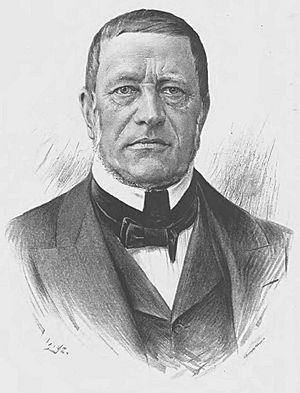

František Palacký

|

|

|---|---|

|

|

| MP of Bohemian provincial diet | |

| In office 1861–1876 |

|

| MP of Imperial Diet | |

| In office 1848–1849 |

|

| Personal details | |

| Born | June 17, 1798 Hodslavice, Moravia, Habsburg Monarchy |

| Died | May 26, 1876 (aged 77) Prague, Bohemia, Austria-Hungary |

| Nationality | Czech |

| Political party | Old Czech Party |

| Spouse | Terezie Měchurová |

| Children | Jan Křtitel Kašpar Palacký Marie Riegrová-Palacká |

| Profession | Politician Historian |

František Palacký (born June 17, 1798 – died May 26, 1876) was a very important Czech historian and politician. Many people called him the "Father of the Nation" because he was so influential during the time when the Czech people were trying to bring back their language and culture. This period is known as the Czech National Revival.

Contents

Life of František Palacký

František Palacký was born on June 17, 1798, in a village called Hodslavice in Moravia. This area is now part of the Czech Republic. His family had a special history. They were part of a group called the Bohemian Brethren. This group secretly kept their Protestant faith during times when it was not allowed.

Palacký's father was a schoolmaster and a learned man. In 1812, František went to a school in Bratislava, which was then in Hungary. There, he met a language expert named Pavel Jozef Šafárik. Palacký became very interested in Slavic languages. He learned 11 languages and knew a few others!

Becoming a Historian

After working as a private teacher for some years, Palacký moved to Prague in 1823. In Prague, he became good friends with Josef Dobrovský. Dobrovský helped protect Palacký from the government, which was often suspicious of people studying Slavic topics.

Dobrovský also introduced Palacký to Count Sternberg and his brother Francis. Both brothers were very interested in Bohemian history. Count Francis helped start the Society of the Bohemian Museum. This society collected old documents about Bohemian history. Their goal was to help people feel proud of their nation again by studying its past.

Public interest in this movement grew in 1825. This was when the new Časopis Českého musea (Journal of the Bohemian Museum) was first published. Palacký was its first editor. The journal was first printed in both Czech and German. The Czech version became the most important literary magazine in Bohemia.

Palacký got a small job as an archivist for Count Sternberg. In 1829, the Bohemian government wanted to give him the title of "historiographer of Bohemia" with a small salary. But it took ten years for the government in Vienna to agree to this.

Writing Czech History

Meanwhile, the Bohemian government agreed to pay for Palacký's most important work. This was a book called Dějiny národu českého v Čechách a v Moravě. Its title means "History of the Czech Nation in Bohemia and Moravia."

This huge book covers Czech history up to the year 1526. That year was when Czech independence ended. Palacký said he "would have to lie" if he wrote about history after 1526. He did a lot of hard work, researching in archives in Bohemia and libraries across Europe. His book is still considered a very important source of information.

The first part of the book was printed in German in 1836. Later, it was translated into Czech. The police censorship made it difficult to publish the book. They were especially strict about his parts on the Hussite movement. This was a religious reform movement in Bohemia.

Palacký was proud of his nation and his Protestant beliefs. But he was careful not to praise the reformers too much without question. However, the authorities still thought his writings were dangerous to the Catholic Church. He had to remove parts of his story. He also had to accept parts that the censors added.

After censorship ended in 1848, he published a new edition. This one was finished in 1876. In it, he put back the original parts of his work.

Entering Politics

The Revolutions of 1848 pushed Palacký into politics. He wrote a famous letter called Psaní do Frankfurtu (A Letter to Frankfurt). In it, he refused to join a German parliament meeting in Frankfurt. He said that as a Czech, he was not interested in German matters.

In June 1848, he led the Slavic Congress in Prague as its president. Later that year, he was sent to the Reichstag, which was a parliament. It met in the town of Kroměříž from October 1848 to March 1849.

At this time, Palacký wanted a strong Austrian empire. He thought it should be a group of southern German and Slavic states. Each state would keep its own rights. This idea was called Austroslavism. His ideas were considered in Vienna. Palacký was even offered a job in the government.

But the idea of a federation failed. The group that wanted strict control won in 1852. This led Palacký to leave politics for a while.

However, after some changes in 1860 and 1861, he became a member of the Austrian senate for life. His ideas did not get much support there. He stopped attending the senate from 1861 onwards, except for a short time in 1871. This was when the emperor gave hope for Bohemian self-government.

In the Bohemian Diet (which was like a local parliament), he became the main leader of the nationalist-federal party. This party wanted a Czech kingdom that included Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia. To achieve Czech self-rule, he even worked with conservative nobles and very strong Catholics. He also went to a Panslavist congress in Moscow in 1867. František Palacký died in Prague on May 26, 1876.

Legacy

Palacký is seen as one of the three "Fathers of the Nation." The first was King Charles IV. The second is František Palacký. The third is President Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk. People sometimes prefer one over the others.

When it comes to historians, no one has written a better history of Bohemia than Palacký. Even historians who focus on smaller time periods have been influenced by his work.

Works

František Palacký wrote many important works, including poetry and historical books.

Poetry

- Na horu Radhošť – a poem

- Má modlitba dne 26. července 1818 – a hymn

- Ideál říše – an ode from 1920

Other Works

- Würdigung der alten böhmischen Geschichtschreiber (Prague, 1830) – This book discussed old Bohemian historians.

- Dějiny národu českého v Čechách a v Moravě I–V (History of the Czech Nation in Bohemia and Moravia), 1836–1867 – His most famous historical work.

- Archiv český (6 vols., Prague, 1840–1872) – A collection of Czech documents.

- Urkundliche Beiträge zur Geschichte des Hussitenkriegs (2 vols., Prague, 1872–1874) – Documents about the Hussite Wars.

- Documenta magistri Johannis Hus vitam, doctrinam, causant ... illustrantia (Prague, 1869) – Documents about the life and teachings of Jan Hus.

- With Šafařík, he wrote Anfänge der böhmischen Dichtkunst (Pressburg, 1818) and Die ältesten Denkmäler der böhmischen Sprache (Prague, 1840) – Books about early Bohemian poetry and language.

- Three volumes of his Czech articles and essays were published as Radhost (3 vols., Prague, 1871–1873).

See also

In Spanish: František Palacký para niños

In Spanish: František Palacký para niños

- František Ladislav Rieger

- Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk

- Palacký University, Olomouc

| Kyle Baker |

| Joseph Yoakum |

| Laura Wheeler Waring |

| Henry Ossawa Tanner |