Fueros de Sobrarbe facts for kids

The Fueros de Sobrarbe (pronounced FWEH-rohs deh soh-BRAHR-beh), also known as the Charters of Sobrarbe, are a legendary set of laws. People believed these laws were created around the year 850 in the Pyrenees mountains, in a valley called Sobrarbe.

The story says these laws were made by Christian people escaping the Muslim invasion of Spain. These laws were special because they put "laws before kings." This meant that even a king had to follow the laws.

For many centuries, people studied and used these Fueros to support their own rights. However, today, historians agree that the Fueros de Sobrarbe were not real. They were made up much later.

In the 1200s, cities and nobles in the kingdoms of Navarre and Aragon started using these legendary laws. They used them to prove their own legal rights and special privileges. The first time the Fueros de Sobrarbe are mentioned is in a fake version of the city charter of Tudela. This fake document was made to look like it was from 1117.

The original charter of Tudela was probably written between 1119 and 1121. But it was changed around the time Theobald I of Navarre became king (1234-1253). King Theobald I had inherited a kingdom far away from his home. He agreed to write down the laws of his new kingdom. The people of Tudela then gave him a changed version of their city charter. This version mentioned the Fueros de Sobrarbe for the first time. It said these Fueros were the basis of their historical rights.

In 1237, King Theobald I agreed to confirm this changed charter. After this, the Fueros de Sobrarbe appeared in many city charters of towns in Aragon and Navarre. They even made it into the main law books of both kingdoms: the Fueros of Navarre (1238) and the Fueros de Aragon (1283). In both, the Fueros were presented as the historical foundation of these kingdoms and their rules.

A legal historian named Jerónimo Blancas wrote about the Fueros de Sobrarbe in detail. His book, Aragonensium rerum commentarii, was published in 1587. Blancas, like others before him, used the Fueros to explain parts of Aragonese law. He especially focused on the Justicia de Aragon, a special judge, and the idea that kings had to follow laws. Today, historians believe the Fueros de Sobrarbe were a medieval fake. They think the versions described by Blancas were made up by many different writers over several centuries. This started with the Tudela charter in the mid-1200s.

The Fueros de Sobrarbe are important not because they were real, but because people believed in them for so long. Until the 1700s, they were seen as the basis for many rules in Navarre and Aragon. They also represented the important idea of "laws before kings."

Contents

Understanding the Fueros de Sobrarbe Story

Jerónimo Blancas wrote his book Aragonensium rerum commentarii in 1587. He wrote it during the time of Philip II of Spain. Blancas wanted to explain the history and importance of the Justicia de Aragon. This book tells the history of the kingdom and the role of the Justice. It starts with a Kingdom of Sobrarbe that Blancas believed existed before the Kingdom of Aragon.

A key part of this founding story is about the laws the first settlers of Sobrarbe wrote. This happened, according to Blancas, between their fourth and fifth kings. These kings were Sancho Garcés (815–832) and Íñigo Arista (868–870). Blancas said the Fueros de Sobrarbe were six basic laws. King Íñigo Arista swore to follow these laws when he became king of Sobrarbe. This showed he wanted himself and future kings to rule under the law.

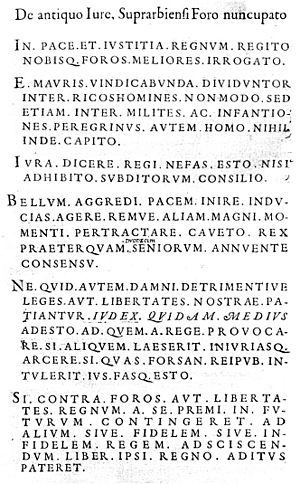

Here are some of the laws Blancas said were in the Fueros de Sobrarbe:

I. You must rule the kingdom with peace and fairness, and give us better laws.

II. Any land taken from the Moors should be shared. It should go to rich men, knights, and nobles, but not to foreigners.

III. The king cannot make laws without asking his people what they think.

IV. King, you must not start a war, make peace, or agree to a truce without the council of older, wise people.

V. To protect our laws and freedoms, a special Judge will watch over us. People can appeal to this Judge if the King harms anyone. The Judge can also stop the King from doing harm to the public.

Blancas said King Arista himself added a sixth law:

VI. If the King ever rules the kingdom like a tyrant, against our laws or freedoms, the kingdom can choose another king. This new king could even be a pagan.

This story allowed Blancas to connect the Justice and the Fueros to the very beginning of the Kingdom of Aragon. It made them seem as old as the kingdom itself.

How the Fueros Story Was Created

The historical story Blancas told developed over five centuries. It came from two main sources. The first was the Fuero of Tudela (Charter of Tudela). The second was the writings of medieval Aragonese lawyers who worked with the Justicia de Aragon. Blancas's story of early Aragon, including a Kingdom of Sobrarbe and its kings, was questioned even in his own time. It seems to have come from attempts to combine older, even stranger stories.

The Tudela Charter's Role

The first time the Fueros of Sobrarbe are mentioned is in the city charter that King Alfonso I gave to the city of Tudela. The document we have today is dated 1117. This was the year the city was taken from the Arabs. The original document, likely from 1119 to 1124, is now lost.

The copies of the Tudela charter we have start by talking about the Fueros of Sobrarbe. They describe how Spain was lost and how some knights hid in the mountains of Sobrarbe. These knights started arguing about how to share what they took from raids. To stop fighting, they asked for advice from a religious leader named Apostolic Aldebrano. He told them to choose a king and write their laws first. So they wrote their laws, then chose Don Pelayo as king. Before he became king, they made him swear to several laws. These included always improving their laws, sharing conquered lands with nobles (not foreigners), not appointing foreign officials, and always asking his nobles before making big decisions like war or peace.

The Tudela charter mentions Sobrarbe like this:

... I give and grant to all the people living in Tudela, and also in Cervera and Gallipienzo, those good laws of Sobrarbe, so that they may have them like the best nobles of my whole kingdom ...

Historians today believe this part, mentioning the Fueros de Sobrarbe, was added later. It was likely put into the original charter around the 1230s. During the reign of Sancho VII the Strong (1157-1234), the city of Tudela in Navarre had lost some land to the king. The king lived in the city, and new taxes were put on the city to pay for his wars and court.

When King Sancho VII died, the throne of Navarre went to his nephew, Teobaldo I (1201-1253). When Teobaldo I became king, he had to make deals with the nobles and cities of Navarre. He agreed to write down their traditional laws. This led to the first Fueros of Navarre, approved in 1238.

Taking advantage of the new king, the city of Tudela changed its charter after 1234. They did this to claim more rights and limit the king's power. They finally reached an agreement with Teobaldo I in 1237. This agreement mostly confirmed the changed Tudela charter. The main changes were the claim that Tudela's citizens had inherited the Fueros de Sobrarbe. These Fueros supposedly gave the city the right to appoint its own Justicia to stop royal orders. They also claimed tax breaks and large land rights for Tudela. This included control over Cervera and Gallipienzo, as mentioned above.

There is proof that the Tudela charter was faked. The existing charter has confusing dates. Later mentions suggest it was issued between 1119-1124, but the charter itself is dated 1117. Also, the original copy of the Tudela charter is lost. All copies we have are from after 1234. The charter uses the royal title Aldeffonsus, rex Aragonie et Nauarre ("Alfonso, king of Aragon and Navarre"). This title only started to be used about 50 years after King Alfonso's reign, during the time of Sancho VII the Strong.

Also, the charter supposedly gave Tudela control over towns like Cervera and Gallipienzo. But these towns were still under Arab control in 1117. Other towns like Corella and Cabanillas, which Tudela wanted in the 1230s, actually got their own separate charters in 1120 and 1124.

Other evidence against the Fueros de Sobrarbe being real comes from the charters of Alquézar (1075) and Barbastro (1100). These towns were conquered and settled by people from Sobrarbe itself. But neither of their charters mentions the Fueros of Sobrarbe. This would be strange, as new territories usually inherited older laws. The rights in these charters are also different from those supposedly in the Fueros de Sobrarbe.

Other nearby city charters from before Tudela's, like the Fuero de Estella (1076-1084) or the Fuero de Jaca (1063 or 1076-1077), also do not mention the Fueros de Sobrarbe. Finally, it seems unlikely that a charter like the Fuero de Sobrarbe, supposedly from the 800s for a small village, would grant rights fit for 13th-century nobles and cities.

The Tudela addition of the Fueros de Sobrarbe was then copied into many later medieval charters in Navarre and Aragon. The Fuero General de Navarra of 1238 already included them. This introduction, likely based on the Tudela charter, describes a legendary Kingdom of Sobrarbe. It combines different stories, some possibly from the Liber regum. This seems to be where three of the first four Fueros of Sobrarbe came from. This is important because it built the legend of "laws before kings." It described how the laws were written before the king was chosen.

After the 1200s, lawyers and historians started using the Fueros of Sobrarbe in legal documents. They used them to justify the power of certain medieval institutions in Navarre and Aragon. These included the Justicia, the bailiffs, and the regular meetings of their parliaments. They claimed these institutions were based on the old, lost Fueros de Sobrarbe.

Old Stories and New Explanations

The traditional story of the Fueros of Sobrarbe was mostly set by the 1400s. However, this story had many parts that did not make sense. For example, how could Don Pelayo have approved laws for a valley in the Pyrenees? This valley was hundreds of miles from his own land in Asturias. Also, he would have been dead for almost a century by then.

In the mid-1400s, Gualberto Fabricio de Vagad tried to make the story more believable. He used historical documents like De rebus Hispaniae and the Chronicle of San Juan de la Peña. Vagad said the early kings of Aragon and Navarre were only small kings ruling the valley of Sobrarbe. So, the origins of both Navarre and Aragon would be in the mythical Kingdom of Sobrarbe.

In Vagad's story, the first true king of Aragon was Ramiro I (1007-1063). The first king of Sobrarbe was García Jiménez (late 800s). Vagad claimed the office of the Justicia was created during García Jiménez's rule. According to Vagad, when Iñigo Arista (around 790–851) became king of Sobrarbe, he allowed his people to rebel if he broke the fueros. This showed he intended to rule by law. His successor, García Jiménez, supported this right by creating the Justicia. This meant the Justicia would have existed since the 800s to protect against kings abusing their power.

This explanation by Vagad, which Blancas largely accepted, has problems. Arista ruled from Pamplona, and García Jiménez likely from Álava, not Sobrarbe. Also, even though the Fueros de Sobrarbe were mentioned in Navarre (Arista's kingdom) and Aragon, Navarre's rules were very different. Navarre did not have a powerful office like the Justicia of Aragon. This seems to have been an Aragonese idea.

However, Vagad did make the Fueros de Sobrarbe story seem more possible. He replaced Pelagius with Iñigo Arista, who was more likely to be active in the Sobrarbe area. Even though the real Arista was probably dead when the Fueros were supposedly made, Vagad linked them more strongly to his successor, García Jiménez.

Carlos, Prince of Viana, who was heir to the crowns of Aragon and Navarre, wrote a Chronicle of the kings of Navarre in the mid-1400s. This chronicle also used De rebus Hispaniae and the Chronicle of San Juan de la Peña. This chronicle changed the founding story of Navarre and Aragon in Sobrarbe. It named Pope Hadrian instead of Apostolic Aldebrano. It made the knights both Navarrese and Aragonese mountain people, not Visigothic knights. It also removed Don Pelayo and put Iñigo Arista in his place. This new story aimed to fix the old story's mistakes and make it more official. It explained the constitutional beginning of the Navarrese and Aragonese monarchies.

The Justice of Aragon and Martin Sagarra's History

According to the list of Justices of Aragon in Jerónimo Blancas's book, Martin Sagarra was a Justice after Fortún Ahe (appointed 1275 or 1276) and before Pedro Martínez de Artasona (Justice in 1281). Blancas admitted he wasn't sure when Sagarra was Justice. But he said if Sagarra was a Justice, it was before Jimén Pérez de Salanova, who took the job in 1294. Other writers doubt Sagarra was a Justice. They think he was a lawyer who might have been a deputy to the Justice, and who lived decades later.

Martin Sagarra is named as Justice of Aragon in the Glossa de Observantis Regni Aragonum. This work was written by Johan Antich de Bages between 1450 and 1458. Blancas likely used this as a source. In this detailed collection of Aragonese legal writings, Antich says the Justice's office was created at the same time as the king's. He quotes a work by Sagarra.

According to Sagarra, Iñigo Arista was chosen as king only if he agreed to appoint a judge. This judge would settle disagreements between the king and his people. The king had to keep this office forever. If he didn't, his people could remove him and choose another king, even a pagan. Antich then says this was the Privilege of the Union, which was ended in 1348. This privilege meant the Justice had to be involved in any case about the privilege. It also allowed rebellion if the king did not follow the privileges. When the privilege was removed, Peter IV ordered all copies destroyed. He also forbade anyone from copying or owning them. However, at least one copy survived. It ended up with Jerónimo Zurita, and later with Blancas himself. Ralph Giesey thought Sagarra must have written his work after 1348. He believed Sagarra was describing the Privilege of the Union, not some ancient fueros. But the privilege might have put an old oral tradition into writing.

Later writers, like Fabricio de Vagad, connected the two sources of the Fueros of Sobrarbe. He added the fueros described by Antich to the list in the Fuero de Tudela. Vagad described the first Navarrese-Aragonese kings as kings only of Sobrarbe. This was until Ramiro I, who also appears as the first king of Aragon. In his version of history, the first king of Sobrarbe is García Jiménez. The first Justice already served during his reign. When Íñigo Arista accepts the crown, he offers the right to rebellion if he breaks the fueros. This was to show he would rule according to the law.

The New Compilation of the Fueros and Observancias, published in 1552, included a mention of the Fueros de Sobrarbe for the first time. It called them the ancient fueros of the kingdom of Aragon. It described the early history of the kingdom similar to the Fuero de Tudela. But it only featured Aragonese people and did not name kings. It also stated that in Aragon, "first there were laws rather than kings." However, the compilation did not list what those first fueros were.

Jerónimo Blancas's Important Work

Jerónimo Blancas started making a list of the Justices of Aragon he knew about in 1578. He wanted to write a commentary on each of them. By 1583, his work, written in Latin, had grown a lot. Blancas called it Commentarios in Fastos de Iustitiis Aragonum (Commentaries on the Justices of Aragon).

Blancas asked the Council of Aragon for permission to publish it, but they said no. However, King Philip II of Spain changed their decision. He allowed Blancas to publish it, but only if he made some changes. The Council thought the book praised the Justicia too much. So, Blancas had to remove the legendary oath of the kings of Aragon and the text of the Privilege of the Union. The book was finally published in 1587. It was called Aragonensium rerum Commentarii (Commentaries on the things of Aragon).

At this time, relations between the king's court and the Aragonese institutions were tense. There was a rebellion in Ribagorza. Aragonese people also disliked the growing power of the Inquisition and the Royal Court. This conflict would later lead to the Alteraciones de Aragón, a major uprising.

In this book, Blancas combined the two sources of the legendary Fueros de Sobrarbe. Blancas changed the founding story created by Carlos de Viana. He made the knights only Aragonese this time. He clearly called the original fueros Fueros de Sobrarbe. Blancas listed them as six separate fueros. He added a first fuero that he invented himself. He also translated them into Latin, like the Law of the XII Tables, to make them seem more important. He also made the role of the rich men smaller, mentioning them only once. He put them on the same level as knights and nobles. Blancas's publication of the Fueros de Sobrarbe gave them a lot of credibility. It took centuries for people to start questioning them.

See also

In Spanish: Fueros de Sobrarbe para niños

In Spanish: Fueros de Sobrarbe para niños

| Aurelia Browder |

| Nannie Helen Burroughs |

| Michelle Alexander |