GNU General Public License facts for kids

| GPLv3 Logo.svg | |

| Author | Richard Stallman |

|---|---|

| Version | 3 |

| Copyright | Free Software Foundation |

| Published | 25 February 1989 |

| DFSG compatible | Yes |

| OSI approved | Yes (applies to GPLv3-only and GPLv2-only) |

| Copyleft | Yes |

| Linking from code with a different license | Software licensed under GPL-compatible licenses only, with the exception of the LGPL, which allows all programs. |

The GNU General Public Licenses (often called GNU GPL or just GPL) are special rules for computer programs. They are like a promise that gives everyone who uses the software certain freedoms. These freedoms include being able to run, study, share, and even change the software.

The GPL was the first "copyleft" license. This means that if you use software with a GPL license and make changes to it, you must share your changes under the same rules. This helps keep the software free for everyone. Richard Stallman, who started the Free Software Foundation (FSF), wrote the first GPL for the GNU Project.

Many popular free software programs use the GPL. For example, the Linux kernel, which is a main part of many operating systems, uses the GPL. Experts like David A. Wheeler say that the GPL's "copyleft" rule was very important for Linux's success. It made sure that programmers who helped build Linux knew their work would stay free and benefit everyone.

In 2007, a newer version of the license, GPLv3, was released. It fixed some issues that had come up with the older GPLv2. Some software projects let users choose between the original GPL terms or newer versions. Other projects, like the Linux kernel, stick to GPLv2 only.

Since the 2010s, the use of GPL has slowly gone down. Some people find it a bit complicated. Others feel it might limit how much open-source software can grow and be used by businesses today.

Contents

History of the GPL

The first GPL was created by Richard Stallman in 1989. He made it for programs that were part of the GNU Project. Before this, different GNU programs had similar but separate licenses. Stallman wanted one license that could be used for all projects. This would make it easier for different programs to share their code.

GPL Version 2

| Published | June 1991 |

|---|---|

The second version, GPLv2, came out in 1991. Over the next 15 years, people in the free software world noticed some problems with GPLv2. These problems could allow companies to use GPL software in ways that went against its main idea of freedom.

Some of these issues included:

- Tivoization: This is when GPL software is put into devices that stop users from running their own changed versions of the software.

- Compatibility problems: It was hard to combine GPLv2 software with other licenses like the AGPL.

- Patent deals: Some companies made deals about patents that seemed to go against the free software community.

To fix these issues, GPLv3 was developed and officially released on June 29, 2007.

GPL Version 1 Details

| Published | 25 February 1989 |

|---|---|

Version 1 of the GNU GPL came out on February 25, 1989. It was made to stop two main ways that software companies limited user freedoms.

First, companies might only release programs that computers can understand (binary files). These files are hard for humans to read or change. GPLv1 said that if you copy and share a program, you must also make its human-readable source code available under the same rules.

Second, companies might add extra rules to the license or combine the software with other software that had different rules. This could make the combined software too restrictive. GPLv1 said that any changed versions of the software must be shared under GPLv1 rules. This meant GPLv1 software could be mixed with less strict software. But it could not be mixed with more strict software, because that would break the GPLv1 rule.

GPL Version 3 Details

| Published | 29 June 2007 |

|---|---|

The Free Software Foundation (FSF) started working on GPLv3 in late 2005. The first draft was published on January 16, 2006, and people could give their opinions. The final GPLv3 was released by the FSF on June 29, 2007. Richard Stallman wrote it with help from lawyers Eben Moglen and Richard Fontana.

Stallman said the most important changes in GPLv3 were about software patents, how well licenses work together, what "source code" means, and rules against hardware stopping software changes (like tivoization). Other changes helped with international use and how to handle license rule-breaking.

The GPLv3 also made it possible to combine software with the Apache License version 2.0. It also tried to prevent deals like the one between Microsoft and Novell that some saw as unfair to free software.

Some important Linux kernel developers, like Linus Torvalds, did not like parts of the GPLv3 drafts. They worried about rules on DRM (digital rights management) and patents. Linus Torvalds decided not to use GPLv3 for the Linux kernel.

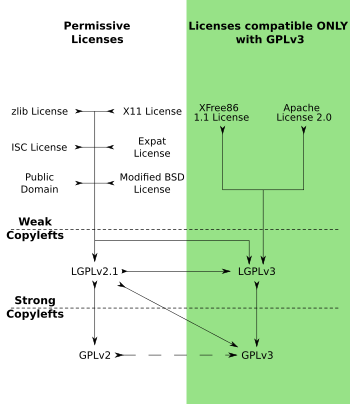

GPLv3 made it easier to work with other free software licenses. However, GPLv3 software could only be combined with GPLv2 software if the GPLv2 license included an "or any later version" option. Many projects, like the GNU Project, use this "or later" clause. But the Linux kernel does not.

What the GPL Allows

The GPL has terms and conditions that anyone receiving a copy of the software must agree to. If you follow these rules, you can change the software, copy it, and share it with others. You can even charge money for this service, or give it away for free. This is different from some licenses that stop you from selling software. The FSF believes that free software should not limit how it can be used for business.

The GPL also says that you cannot add "further restrictions" to the rights it gives. This means you cannot make people sign secret agreements or other contracts that limit their freedom with the software.

If you share programs that are already put together (like an app you download), you must also provide the source code. The source code is the human-readable version of the program. You can do this by including the source code, offering to send it, or telling people where to download it. The GPLv3 makes it even easier to share source code, like through peer-to-peer sharing.

The FSF does not own the copyright for every program released under the GPL. Usually, the person who created the software owns the copyright. Only the copyright owner can take legal action if someone breaks the license rules.

How You Can Use GPL Software

You can use software under the GPL for any purpose, even for business. You can even use GPL-licensed tools, like compilers, to create software that is not free. People or companies who share GPL software can charge money for copies or give them away for free. This is a key difference from "shareware" or "proprietary" software, which often limit copying or commercial use.

If you use GPL software only for yourself or within your company, without sharing it with others, you can change it and reuse parts without having to release your changes. But if you sell or share the software, you must make the entire source code available to others. This includes any changes you made. This is how "copyleft" works to keep the software free for everyone.

However, if you run a program on a GPL-licensed operating system (like Linux), that program itself does not have to be GPL. Its license depends on the libraries and parts it uses, not on the operating system it runs on. For example, if your program is all new code, it doesn't need to be GPL. Only if your program uses parts of GPL-licensed code and you share it, then your whole program must be shared under the GPL. The GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL) is a weaker version of the GPL. It lets you use LGPL-licensed parts in your program without making your whole program GPL.

GPLv3 also says that GPL-licensed code cannot be used to create "technical protection measures" (like DRM) that stop users from exercising their rights under the license. This means you cannot be sued for getting around DRM if you are doing so to use the software as the GPL allows.

What is Copyleft?

"Copyleft" is a special rule in the GPL. It means that if you share a GPL-licensed program that you have changed, you cannot add new rules that make it less free. The rules for sharing the whole program cannot be stricter than what the GPL allows.

This rule works because of copyright law. Normally, copyright stops people from sharing or changing software without permission. But the GPL uses copyright law in a different way. It gives everyone permission to share and change the software, as long as they also give the same freedoms to others. This helps make sure the software and all its changed versions stay free.

Many times, when you get a GPL program, the source code comes with it. Another way to follow the copyleft rule is to offer to send the source code on a CD or let people download it from the internet.

Copyleft only applies when you share the program with others. If you make changes to a GPL program and only use it yourself, you don't have to share your changes. Also, copyleft applies to the software itself, not usually to what the software creates. For example, if a website uses a GPL-licensed content management system, the website itself doesn't have to share its changes to the system, because the website is not being "redistributed."

Legal Status of the GPL

The GPL is a real and enforceable legal license. This means that if someone breaks the rules of the GPL, they can be taken to court.

One of the first known times the GPL was broken was in 1989. A company called NeXT changed the GCC compiler but didn't release their changes. After being asked, they released a public update. No lawsuit was filed then.

In 2002, a company called MySQL AB sued another company, Progress NuSphere. MySQL said NuSphere broke its copyright by using MySQL's GPL-licensed code without following the license. They settled the case later. The judge in that case made it clear that the GPL is a valid and binding license.

In 2004, a project called netfilter/iptables won a court case in Germany against Sitecom Germany. Sitecom was sharing Netfilter's GPL software but not following the license rules. The court said that breaking the GPL rules was a copyright violation. This was an important ruling because it showed that the GPL is legally binding in Germany.

Since then, there have been other cases where the GPL has been upheld in court. For example, in 2006, the gpl-violations.org project won a case against D-Link Germany for using parts of the Linux kernel without following the GPL. In 2008, the Free Software Foundation sued Cisco Systems, Inc. for not following the GPL with their Linksys products. Cisco settled the case by agreeing to follow the GPL rules and making a donation to the FSF.

These cases show that the GPL is a serious legal document. Companies and individuals who use GPL-licensed software must follow its rules, or they could face legal action.

How GPL Works with Other Licenses

Software licensed under the GPL can often be combined with code that has other licenses. This works as long as the combined rules don't add more limits than the GPL allows.

Here are some key points:

- If you want to combine code from different GPL versions, it usually works only if the older GPL version says "or any later version." For example, a library with GPLv3 cannot be used by a program that is "GPLv2-only."

- Code under the LGPL can usually be linked with any other code, no matter its license. However, the LGPL does add some extra rules for the combined work.

- The FSF keeps a list of licenses that are "GPL-compatible." This list includes many common licenses like the MIT License, the BSD license, and the Artistic License 2.0.

Some businesses use "multi-licensing." This means they offer their software under the GPL, but also sell a special license for companies that want to combine it with their own secret code. Examples include MySQL AB and Digia PLC (with Qt framework).

GPL for Text and Other Media

The GPL can also be used for text documents or other types of media. But for manuals and textbooks, the FSF usually suggests using the GNU Free Documentation License (GFDL) instead. However, some groups, like Debian developers and the FLOSS Manuals foundation, prefer to use the GPL for their documentation because the GFDL can be harder to combine with GPL software.

If the GPL is used for computer fonts, it can get a bit tricky. Sometimes, documents or images made with these fonts might also need to be shared under the GPL. This depends on how copyright laws treat fonts in different countries. To avoid this problem, the FSF provides a special GPL font exception.

How Popular is the GPL?

Historically, the GPL has been one of the most popular software licenses for free and open-source software (FOSS).

In 1997, a survey showed that about half of the software in a large archive used the GPL. By 2000, about 53% of the source code in Red Hat Linux 7.1 was under the GPL. In 2003, about 68% of projects on SourceForge.net used the GPL. By August 2008, the GPL family made up 70.9% of the free software projects listed on Freecode.

After GPLv3 came out in June 2007, some big projects decided not to switch to it. For example, the Linux kernel, MySQL, and MediaWiki stayed with GPLv2. However, two years later, Google reported that 50% of GPL-licensed open-source projects on Google Code had moved from GPLv2 to GPLv3.

By 2011, data showed that GPLv2 was still very popular (42.5% of open-source projects), while GPLv3 was used by 6.5%. Some analysts suggested that "copyleft" licenses were becoming less common, and "permissive" licenses (which have fewer rules) were becoming more popular.

In 2015, the MIT license became more popular than GPLv2, making GPLv2 second place. GPLv3 dropped to fourth place. However, in 2016, an analysis of the Fedora Project showed that the GNU GPLv2 or later was still the most popular license there.

By April 2018, a study of the FOSS world showed that the MIT license was most popular (26%), followed by Apache 2.0 (21%), GPLv3 (18%), and GPLv2 (11%). This shows that while the GPL is still widely used, other licenses have become more common in recent years.

Other Things to Know

- Criticism of copyright

- Multi-licensing

- European Union Public Licence (EUPL)

- GNU Lesser General Public License (LGPL)

- GNU Affero General Public License (AGPL)

- GPL font exception

- GPL linking exception

- Comparison of free and open-source software licenses

- Free-software license

- Category:Software using the GNU General Public License

- Public information licence

See also

In Spanish: GNU General Public License para niños

In Spanish: GNU General Public License para niños

| Dorothy Vaughan |

| Charles Henry Turner |

| Hildrus Poindexter |

| Henry Cecil McBay |