Geology of Minnesota facts for kids

Minnesota's geology is all about its rocks, minerals, and soils. It also covers how they formed, changed, spread out, and what they're like today.

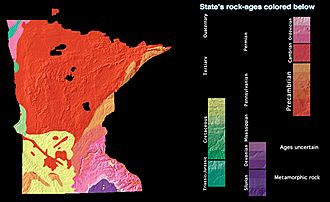

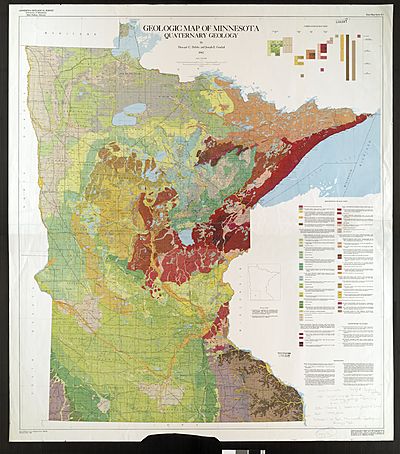

The state's geological story can be split into three main parts. The first was a very long time, from when Earth was young until about 1.1 billion years ago. During this period, Minnesota's ancient bedrock formed from volcanoes and layers of sediment. It was then shaped by cracks (faulting), bends (folding), and wearing away (erosion). In the second period, many layers of sedimentary rock formed from dirt and sand washed in by rivers and repeated times when the sea covered the land. In the third and most recent period, starting about 1.8 million years ago, glaciers scraped away old rock formations. They also left behind thick layers of rock and dirt (glacial till) over most of the state. These glaciers also created the beds and valleys of today's lakes and rivers.

Minnesota's natural resources have been key to the state's economy for a long time. Very old bedrock has been mined for metals, especially iron ore, which built the economy of Northeast Minnesota. Ancient granites and gneisses (a type of rock), and later limestones and sandstones, are quarried for building stone and monuments. Glacial deposits are mined for gravel and sand. The rock and dirt left by glaciers and old lakebeds formed the rich soil for the state's farms. Also, the many lakes created by glaciers are a big part of Minnesota's tourism. These natural treasures have shaped Minnesota's history, how people settled, and how trade routes formed along its waterways, valleys, and plains. These routes are now the state's transportation paths.

Geological History

Ancient Bedrock (Precambrian)

Minnesota has some of the oldest rocks on Earth. These are granitic gneisses that formed about 3.6 billion years ago. That's roughly 80% of Earth's age! Around 2.7 billion years ago, the first volcanic rocks that would become part of Minnesota started to rise from an ancient ocean. This formed a huge, stable piece of Earth's crust called the Superior craton. This craton later became part of the Canadian Shield, which is now part of North America. Much of the gneiss rock that is under Minnesota today formed almost a billion years earlier, but it was under the sea. Except for some islands in what is now northern Minnesota, most of the area stayed underwater.

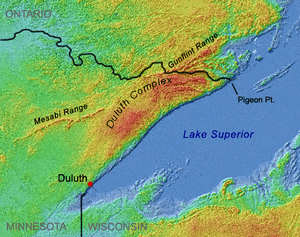

In the Middle Precambrian time, about 2 billion years ago, the land rose above the water. Heavy mineral deposits containing iron had gathered on the shores of the shrinking sea. These formed the Mesabi, Cuyuna, Vermilion, and Gunflint iron ranges. These ranges stretch from the center of the state north into Canada. These areas also show the first signs of life, as algae grew in the shallow waters.

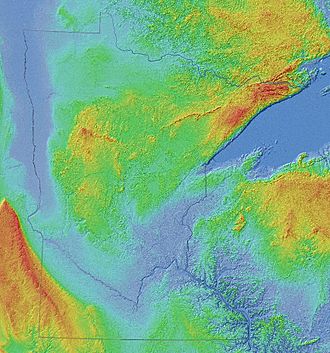

Over 1.1 billion years ago, a huge crack (rift) formed in the land. Lava poured out of cracks along the edges of this rift valley. This Midcontinent Rift System stretched from Michigan north to Lake Superior, then southwest through the lake to the Duluth area, and south through eastern Minnesota into what is now Kansas. The rifting stopped before the land could split into two separate continents. About 100 million years later, the last volcano went quiet.

Later Sedimentary Rock (Late Precambrian and Paleozoic)

The mountain-building and rifting events left high areas above the low basin of the Midcontinent Rift. Over the next 1.1 billion years, the high lands wore down, and the rift filled with sediments. These sediments formed rock that was hundreds to thousands of meters thick. While Earth's huge plates kept moving slowly, the North American craton stayed stable. Even without folding and faulting from plate movements, the region continued to experience slow sinking and rising of the land.

Five hundred fifty million years ago, Minnesota was repeatedly covered by shallow seas that grew and shrank in cycles. The land mass of what is now North America was near the equator, and Minnesota had a tropical climate. Small sea creatures like trilobites, coral, and snails lived in the sea. Their shells sank to the bottom and are now preserved in the limestones, sandstones, and shales from this time. Later, creatures like crocodiles and sharks swam through these seas. Fossil shark teeth have even been found on the high lands of the Mesabi Range. During later eras, other land animals appeared as the dinosaurs vanished. However, much of the evidence from this time has been scraped away or buried by recent ice ages. The rocks remaining in Minnesota from this period are from the Cambrian and Ordovician ages.

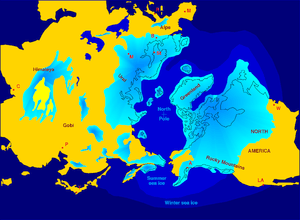

Ice Ages

In the most recent period, starting about two million years ago, huge glaciers grew and shrank across the region. The ice melted away for the last time about 12,500 years ago. Melting glaciers formed many of Minnesota's lakes and carved out its river valleys. They also formed several lakes (proglacial lakes) that shaped the state's land and soils. The biggest of these was Lake Agassiz, a giant lake as big as all the present Great Lakes combined. This lake was blocked by the northern ice sheet, and its huge flow found an outlet in the glacial River Warren. This river drained south across the Traverse Gap through the valleys now used by the Minnesota and Mississippi Rivers. Eventually, the ice sheet melted, and the Red River gave Lake Agassiz a northern outlet toward Hudson Bay. As the lake drained, its bed became peatlands and a fertile plain. Similarly, Glacial Lake Duluth, in the Lake Superior basin, was blocked by a glacier. It drained down the ancient path of the Midcontinent Rift to the St. Croix River and the Mississippi. When the glaciers left, the lake could drain through the Great Lakes to the Saint Lawrence River.

Giant animals roamed the area. Beavers were the size of bears, and mammoths were 14 feet (4.3 m) tall at the shoulder and weighed 10 tons. Even buffalo were much larger than today. The glaciers kept melting, and the climate became warmer over the next few thousand years. The giant creatures died out about 9,000 years ago.

This glaciation drastically changed most of Minnesota. All but two of the state's regions are covered with thick layers of glacial till. The "driftless area" of Southeastern Minnesota was not touched by the most recent glaciation. Because there was no glacial scraping or till, this region has many deep valleys and hills, unlike other parts of the state. Northeastern Minnesota was affected by glaciers, but its very old, hard rocks were more resistant to glacial erosion than the softer sedimentary rocks found elsewhere. So, glacial till is quite thin there. While glaciers clearly eroded the land and left some till, older rocks and landforms are still visible and exposed across much of the region.

Minnesota Today

Today, Minnesota is much quieter geologically than in the past. Outcrops of old lava flows and magma are the only remaining signs of the volcanoes that stopped erupting over 1.1 billion years ago. Being in the middle of the continent, the state is far from the seas that once covered it. The huge continental glacier has completely melted from North America. Minnesota's landscape is mostly flat; its highest and lowest points are only about 518 meters (1,700 feet) apart in elevation.

While the state no longer has true mountain ranges or oceans, it does have a good amount of regional variety in its landforms and geological history. This has affected how Minnesota was settled, its human history, and its economic growth. These different geological regions can be grouped in several ways. The way they are grouped here mostly comes from Sansome's Minnesota Underfoot - A Field Guide to Minnesota's Geology, but also from Minnesota's Geology by Ojakangas and Matsch. These experts generally agree on the borders of the areas.

Northeastern Minnesota: Ancient Bedrock

Northeastern Minnesota is an oddly shaped region. It includes the northeasternmost part of the state north of Lake Superior, the area around Jay Cooke State Park, and much of the area east of U.S. Highway 53. This area is mostly the same as the Northern Superior Uplands Section of the Laurentian Mixed Forest.

Known as the Arrowhead for its shape, this region shows the clearest signs of the state's violent past. You can see rocks that first formed from volcanic activity about 2.7 billion years ago. These include Ely greenstone (a type of rock), which are volcanic rocks that were changed by heat and pressure and folded. There are also Proterozoic formations created about 1.9 billion years ago that gave the area most of its mineral wealth. More recent rocks like gabbro, basalt, and rhyolite formed from magma and lava that rose up and hardened about 1.1 billion years ago during the Midcontinent Rift. The ancient bedrock formed by this activity has been worn away but remains at or near the surface over much of the area.

The entire area is the raw southern edge of the Canadian Shield. The topsoil is thin and poor, and it comes from the rock beneath or nearby, not from thick glacial till. Many of this region's lakes are in dips formed by different parts of the Canadian Shield rock wearing away at different speeds. The cracks that formed then filled with water, creating many of the thousands of lakes and swamps in the Superior National Forest.

After the glaciers melted, Northeastern Minnesota was covered by forest, broken only by these connected lakes and wetlands. Much of the area has not been changed much by people, as there are large forest and wilderness preserves, like the Boundary Waters Canoe Area and Voyageurs National Park. In the rest of the region, lakes offer recreation, forests are managed for wood pulp, and the bedrock below is mined for valuable ores deposited in ancient times. While copper and nickel ores have been mined, the main metal is iron. Three of Minnesota's four iron ranges are in this region, including the Mesabi Range. This range has provided over 90% of the state's iron output, including most of the pure ores that could be used directly in furnaces. The state's iron mines have produced over three and a half billion metric tons of ore. While high-grade ores are now used up, lower-grade taconite still supplies a large part of the nation's needs.

Northwestern Minnesota: Glacial Lakebed

Northwestern Minnesota is a huge, flat plain that was once the bed of Glacial Lake Agassiz. This plain stretches north and northwest from the Big Stone Moraine, beyond Minnesota's borders into Canada and North Dakota. In the northeast, the Glacial Lake Agassiz plain turns into the forests of the Arrowhead. This region includes the lowlands of the Red River watershed and the western half of the Rainy River watershed within the state.

The bedrock in this region is mainly very old (Archean), with small areas of older Paleozoic and younger Mesozoic sedimentary rocks along the western border. By the last ice age (Wisconsinan times), this bedrock had been covered by clayey glacial drift. This drift was scraped and carried from sedimentary rocks in Manitoba. The bottomland is flat and smooth, but it slowly slopes down from about 400 meters (1,300 feet) at the southern beaches of Lake Agassiz to 335 meters (1,100 feet) along the Rainy River. There is almost no change in height, except for benches or beaches where Glacial Lake Agassiz stayed at a certain level before it shrank. In the western part of the region, in the Red River Valley, fine-grained glacial lake deposits and decayed organic materials up to 50 meters (160 feet) deep form rich, well-textured, and moist soils (mollisols). These soils are perfect for farming. To the north and east, much of the land is poorly drained peat, often in unique patterns known as patterned peatland. At slightly higher elevations within these wetlands are areas of black spruce, tamarack, and other water-tolerant trees.

Southwestern Minnesota: Glacial River and Glacial Till

Southwestern Minnesota is in the areas where water flows into the Minnesota River, the Missouri River, and the Des Moines River. The Minnesota River lies in the bed of the glacial River Warren, a much larger river that drained Lake Agassiz when outlets to the north were blocked by glaciers. The Coteau des Prairies divides the Minnesota and Missouri River valleys. It's a striking landform created where different parts of the glacier split and moved. On the Minnesota side of the coteau is a feature called Buffalo Ridge, where wind speeds average 16 mph (26 km/h). This windy plateau is being used for commercial wind power, helping the state rank third in the nation for wind-generated electricity.

Between the river and the plateau are flat prairies on top of varying depths of glacial till. In the far southwest part of the state, outcrops of Sioux Quartzite (a very hard rock) are common. Less common are layers of a changed mudstone called catlinite. Pipestone, Minnesota, is where Native Americans historically quarried catlinite, which is also known as "pipestone." Another notable outcrop in the region is the Jeffers Petroglyphs, a Sioux Quartzite outcrop with many ancient carvings that may be up to 7,000–9,000 years old.

Drier than most of the rest of the state, this region is a transition zone between the prairies and the Great Plains. It was once rich in wetlands known as prairie potholes. However, 90%, or about three million acres (12,000 km²), have been drained for farming in the Minnesota River basin. Most of the prairies are now farm fields. Because of the geology of the region and less rain, groundwater resources are not as plentiful or widespread as in most other areas of the state. Because of this, this rural area has a large network of water pipelines that carry groundwater from the few areas with good wells to much of the region's population.

Southeastern Minnesota: Bluffs, Caves and Sinkholes

Southeastern Minnesota is separated from Southwestern Minnesota by the Owatonna Moraine. This is the eastern branch of the Bemis Moraine, which is an end moraine from the Des Moines lobe of the last Wisconsin glaciation. This moraine runs south from the Twin Cities. Southeastern Minnesota is mostly the same as the Paleozoic Plateau region.

The bedrock here is made of older Paleozoic sedimentary rocks, with limestone and dolomite especially common near the surface. The land is very cut up, and local rivers flowing into the Mississippi have carved deep valleys into the bedrock. It is an area of karst topography (a landscape with caves and sinkholes), with thin topsoils lying on top of porous limestones. This leads to the formation of caverns and sinkholes. The last glaciation did not cover this region (it stopped at the Des Moines end lobe mentioned above). So, there is no glacial drift to form subsoils, giving the region the name "Driftless Area." Since the topsoils are shallower and poorer than those to the west, dairy farming, rather than growing crops, is the main farming activity.

Central Minnesota: Knob and Kettle Country

Central Minnesota is an oddly shaped region that includes:

- The area where water flows into the St. Croix River.

- The area where water flows into the Mississippi River above where it meets the Minnesota River.

- Parts of the Minnesota and Red River areas on the higher glacial lands that divide those two areas from the Mississippi.

- The Owatonna Moraine on a strip of land running from western Hennepin County south to the Iowa border.

- The upper valley of the Saint Louis River and the valley of its main branch, the Cloquet River. These rivers once flowed to the Mississippi but were "captured" by another river, and their waters were sent through the lower Saint Louis River to Lake Superior.

Glacial landforms are the common features of this region. The bedrock ranges in age from very old Archean granites to younger Mesozoic Cretaceous sediments. Under the eastern part of the region (and the southern extension to Iowa) are the Late Precambrian Keweenawan volcanic rocks of the Midcontinent Rift, covered by thousands of meters of sedimentary rocks.

At the surface, the entire region is "Moraine terrain." This means it has many different shapes left by glaciers, like hills (moraines, drumlins, kames), ridges (eskers), and flat areas (outwash plains, till plains). In the many dips formed by glaciers are wetlands and many of the state's "10,000 lakes," which make the area a popular vacation spot. The glacial deposits are a source of gravel and sand. Underneath the glacial till are high-quality granites that are quarried for buildings and monuments.

East Central Minnesota: Bedrock Valleys and Outwash Plain

The subregion of East Central Minnesota is the part of Central Minnesota near where three of the state's great rivers meet. It includes Dakota County, eastern Hennepin County, and the region north of the Mississippi but south of an east-west line from Saint Cloud to the St. Croix River on the Wisconsin border. It includes much of the Twin Cities metropolitan area. This region has the same types of glacial landforms as the rest of Central Minnesota, but it is special because of its bedrock valleys, both active and buried.

The valleys now hold three of Minnesota's largest rivers, which join here. The St. Croix joins the Mississippi at Hastings. Upstream, the Mississippi is joined by the Minnesota River at historic Fort Snelling. When River Warren Falls moved upstream past where the much smaller Upper Mississippi River joined, a new waterfall was created where that river entered the much lower River Warren. The new falls moved upstream on the Mississippi, traveling eight miles (13 km) over 9,600 years to where Louis Hennepin first saw it and named St. Anthony Falls in 1680. Because it was a great source of power, this waterfall determined where Minneapolis would be built. One river flowing from the west, Minnehaha Creek, moved back only a few hundred yards from one of the Mississippi's channels. Minnehaha Falls remains as a beautiful and interesting reminder of River Warren Falls. You can easily see the limestone-over-sandstone rock layers in its small gorge. At St. Anthony Falls, the Mississippi dropped 50 feet (15 m) over a limestone ledge. These waterfalls were used to power the flour mills that helped the city grow in the 1800s.

Other bedrock valleys lie deep beneath the till left by the glaciers that created them. But you can trace them in many places by the Chain of Lakes in Minneapolis and lakes and dry valleys in St. Paul.

North of the metropolitan area is the Anoka Sandplain (a flat, sandy area) from the last ice age. Along the eastern edge of the region are the Dalles of the St. Croix River, a deep gorge cut by water from Glacial Lake Duluth into ancient bedrock. Interstate Park here has the southernmost surface exposure of the Precambrian lava flows of the Midcontinent Rift, giving a peek into Minnesota's volcanic past.

- Wright, W. E. (1990). Geologic History of Minnesota Rivers. Minnesota Geological Survey, Educational Series 7. St. Paul: University of Minnesota. ISSN 0544-3083.

Images for kids

-

Limestone bluffs cut by the Root River in Olmsted County

| Audre Lorde |

| John Berry Meachum |

| Ferdinand Lee Barnett |