Glacial history of Minnesota facts for kids

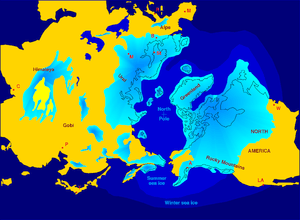

The glacial history of Minnesota is all about how giant sheets of ice, called glaciers, shaped the land. The most important changes happened during the last glacial period, which finished about 10,000 years ago. Over the last million years, huge parts of the Midwestern United States and Canada were covered by these massive ice sheets.

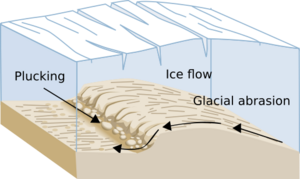

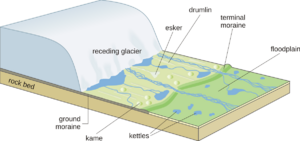

These moving glaciers completely changed the land. They scraped up huge amounts of rock and soil from where they started and dropped it along their edges. This material is called drift or till. Sometimes, this drift filled up old river valleys. Other times, it piled up into hills called terminal moraines at the glacier's edge. Glaciers also have amazing power to carve out the land by scraping and rubbing away rocks.

The glaciers changed Minnesota's landscape a lot. One of the biggest changes was how water flowed. Before the glaciers, most rainwater probably flowed quickly to the ocean. Today, much of the rain and melted snow stays in lakes. Streams wind their way from lake to lake, and only some of the water flows away in rivers. This means the land's drainage system is still quite new. Even the mighty Mississippi River has a deep valley below St. Anthony Falls, but its water doesn't flow freely because of Lake Pepin, which holds some of it back. Rivers have only been carving their paths for about 10,000 years, which is a very short time in Earth's long history!

Contents

How Glaciers Moved Through Minnesota

Minnesota has been covered by glaciers many times. The most recent ice ages were the Wisconsin Episode and Illinoian stages. Before these, ice sheets moved into and out of Minnesota many times during the Pre-Illinoian Stage.

The ice came into Minnesota from three main areas:

- The Labradorian center in northern Quebec and Labrador.

- The Patrician center, southwest of Hudson Bay.

- The Keewatin center, northwest of Hudson Bay.

The rocks and soil left behind by these ice sheets show where they came from. The Keewatin ice picked up limestones and shales from Manitoba and the Red River Valley. The Patrician and Labradorian ice moved over iron-rich, very old rocks from the Canadian Shield.

Older Glacial Periods

It's hard to find places where the older glacial deposits from the Pre-Illinoian or Illinoian stages are visible. In southeastern and southwestern Minnesota, there are large areas of these older deposits. However, they are mostly covered by loess, which is wind-blown silt. Also, the streams in these older areas have had much more time to create good drainage systems compared to areas covered by younger glacial deposits.

Rivers Changed Their Paths

As the huge ice sheets moved into the middle of North America, they blocked rivers. Rivers that used to flow from the Rocky Mountains northeast towards the Arctic Ocean found their paths filled with ice. These rivers had to find new ways around the ice. When the ice melted, the new valleys they carved kept the rivers from going back to their old paths.

The Wisconsin Glacial Period

The Wisconsin glacial episode was the most recent major ice age. It had four main parts, each with ice advancing and then retreating. In Minnesota, we mostly see evidence of the Iowan, Cary, and Mankato parts.

The Iowan deposits are found mainly in southwestern and southeastern Minnesota. These areas have very few lakes because the water has had more time to drain away.

Most of the lakes in Minnesota are found within the areas covered by the Cary and Mankato ice sheets. Let's look at these two in more detail.

The Cary Glaciers

The glaciers that came from northeastern Canada were very thick. They caused a lot of erosion in northeastern Minnesota. This ice sheet, called the "Minneapolis lobe," reached south of Minneapolis. It left behind reddish, sandy soil because it picked up red sandstone and shale from the north. You can also find pebbles of basalt, gabbro, and iron-rich rocks from northeastern Minnesota.

These glaciers created hills called terminal moraines that stretch from northwest of St. Cloud, through the Twin Cities, and into central Wisconsin. They also left reddish sands and gravels in flat areas called outwash plains.

The Mankato Glaciers

After the Patrician ice melted, the last part of the Wisconsin ice age in Minnesota began. The final big advance of the continental glacier reached as far south as Des Moines, Iowa. This glacier came from the northwest and was quite thin, so it didn't cause as much erosion.

This ice sheet, called the Des Moines lobe, created a smaller branch called the Grantsburg sublobe. Another branch, the St. Louis sublobe, also came from the main ice sheet. The soil left by these glaciers is tan to buff in color. It's rich in clay and limestone because it picked up shale and limestone rocks from the northwest. The Superior lobe also formed during this time, reaching as far west as Aitkin County, Minnesota.

The Grantsburg sublobe blocked the flow of the Mississippi River from north of St. Cloud through the Twin Cities. The water, carrying lots of sand, had to flow east around the ice. This created a sandy, triangular area called the Anoka Sand Plain, stretching from St. Cloud to the Twin Cities and northeast to Grantsburg, Wisconsin.

How Lakes Were Formed

Kettle Lakes

As glaciers moved through Minnesota, some pieces of ice got stuck and didn't melt as fast as others. The glaciers continued to drop sediments around and sometimes on top of these isolated ice blocks. When the ice blocks finally melted, they left behind holes in the ground. These holes then filled with melted snow and rain, creating kettle lakes.

Kettle lakes can form in the hilly areas behind the main glacier edges. They can be any size, and their shores can be made of clay, sand, or even large rocks. In very hilly areas, kettles are often small but deep. If the ice melted and left a flat area of sand and gravel (an outwash plain), kettles might form there too. These outwash kettle lakes are usually shallow and fewer in number because the sand can quickly fill them in.

Minnesota has had glaciers move in from both the northeast and northwest. This means the landscape has been shaped by overlapping glacial areas. For example, a sandy outwash plain from an older glacier might now be covered by new deposits from a younger glacier.

Most of the lakes in the world are kettle lakes formed by glaciers. In Minnesota, most kettle lakes are found in the hilly areas left by glaciers.

Lakes Carved from Bedrock

In northeastern Minnesota, the glaciers were thousands of feet thick. As they moved, they carved away huge amounts of rock. Ice itself isn't very rough, but by picking up and moving pieces of rock, it could scrape away softer materials underneath.

In the Arrowhead Region, there are tilted layers of volcanic rocks mixed with softer layers of shale. As the glaciers moved, they removed the softer shale. This created a landscape of hills (made of harder rock) and valleys (where the shale used to be). Many of these valleys are now lakes. Even though the lakes run from west to east, scratches on the rocks show that the ice actually moved from north to south, across the valleys.

Next to this area is Lake Superior. Its basin sits in a billion-year-old dip in the Earth's crust. Before the glaciers, this dip was filled with eroded shale. The thousands of feet of glacial ice scraped away a huge amount of this shale. The ice was so thick that it carved the sandstone down to depths of 700 feet below sea level. Today, Lake Superior is the largest freshwater lake in the world by area.

Glacial Lakes

About 18,000 years ago, the huge Laurentide Ice Sheet began to melt and retreat. As the Mankato ice shrank, meltwater collected in several places along the edge of the glacier. Some of these lakes were enormous, covering hundreds of thousands of square miles. They left clear marks on the land. All of them have since drained naturally or shrunk a lot from their original size.

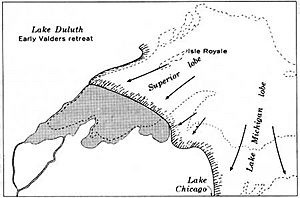

Glacial Lake Duluth

Glacial Lake Duluth was a huge body of water that formed at the southwestern edge of the Superior lobe. It was much larger than today's Lake Superior. Its shorelines were nearly 148 meters higher than Lake Superior is now.

Early on, Lake Duluth drained into the Mississippi River through the St. Croix River Valley. It had two outlets: one along the Kettle and Nemadji Rivers in Minnesota, and another to the east along the Bois Brule River in Wisconsin. Later, as the glacier retreated further northeast, Lake Duluth's waters joined with those in the Michigan and Huron basins. The southern outlets were then abandoned for a lower one on the east end of Lake Superior.

Today, the Kettle River no longer drains Lake Superior, but it flows through a very large valley that it couldn't have created with its current water flow. The Nemadji and Bois Brule Rivers now flow north towards Lake Superior. Even though a lot of water flowed over the southern edge of Lake Superior, the Bois Brule River outlet was never carved deep enough to remove a land divide at its source.

Proglacial Lakes

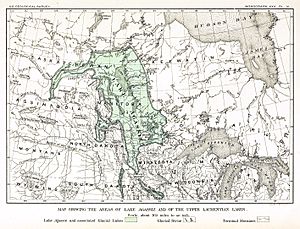

Glacial Lake Agassiz

The largest of all the proglacial lakes was Lake Agassiz. A small part of it covered the area of today's Red River Valley in Minnesota and North Dakota. Glaciers to the north blocked the natural northward flow of water. As the ice melted, a huge lake formed south of the ice.

The water overflowed a land divide at Browns Valley, Minnesota. It drained through the Traverse Gap and carved the valley of the present-day Minnesota River. The amount of water flowing out was incredible! It helped the nearby Mississippi River form a very large valley in southeastern Minnesota.

The river that drained Lake Agassiz is called the Glacial River Warren. It flowed over a ridge of glacial deposits at Browns Valley. As the water eroded these deposits, the lake level dropped. Eventually, so many large boulders were left behind that they formed a "boulder pavement," which stopped the river from carving deeper. The lake level stayed steady for a while. During this time, waves on the lake created noticeable beaches along the shoreline. Glacial material was also being deposited on the bottom of the lake.

Later, the boulders at the lake's outlet were eroded downstream. The river could then carve deeper through a mix of sediments. Again, a boulder pavement formed, and the lake level stabilized at a lower point, creating another set of beaches.

After the ice retreated further into Canada, lower outlets to Hudson Bay were uncovered. The Minnesota Valley outlet was no longer needed. The land divide at Browns Valley became the source for the north-flowing Red River of the North and the southeast-flowing Minnesota River, which is a branch of the Mississippi River.

During its existence, Lake Agassiz might have been the largest freshwater lake ever. The lakebed, made of lake muds and silts, is one of the flattest regions on Earth and is incredibly fertile. No lakes carved from bedrock exist there because the ice was too thin to erode. No kettle lakes are found on the lakebed either, because the lake deposits would have filled in any depressions.

|

| Delilah Pierce |

| Gordon Parks |

| Augusta Savage |

| Charles Ethan Porter |