George J. F. Clarke facts for kids

George J. F. Clarke (born October 12, 1774 – died 1836) was a very important and active person in East Florida during the Second Spanish Period. He was a trusted friend and helper to the Spanish governors from 1811 to 1821. He held several public jobs, including the main surveyor for the area.

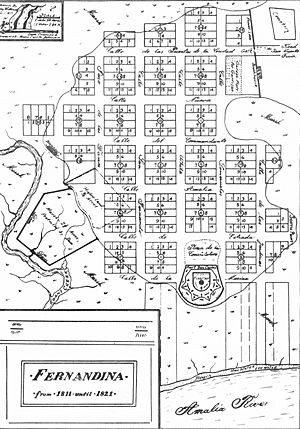

Clarke also served in the Spanish army from 1800 to 1821. He helped defend East Florida during the "Patriot War" in 1812. He also led soldiers against pirates like Gregor MacGregor and Louis-Michel Aury in 1817. In 1811, Governor Enrique White asked him to plan the town of Fernandina and build new houses there. He was key in setting up a local government in the area between the St. Marys and St. Johns rivers. This helped bring peace to that busy region during the last years of Spanish rule.

Clarke oversaw all land surveys in East Florida between 1811 and 1821. He made money by buying and selling large pieces of land, becoming one of Florida's biggest landowners. In his will, he left over 33,000 acres of land, several houses, and other properties to his family. He spoke Spanish very well. Many historians have confused his initials, but his will shows his full name was George John Frederic Clarke.

Later in his life, he invented a sawmill that was powered by horses. It worked so well that the Spanish Governor José Coppinger gave him a special "sawmill grant" of 22,000 acres of timber land. This was more than the usual 16,000 acres. Clarke also wrote articles in the local newspaper, the East Florida Herald. He shared his ideas on farming, growing fruit trees, healthy eating, old ruins (archeology), and how white settlers and Native Americans got along.

Contents

Early Life and Family

George Clarke was born in St. Augustine when it was a British colony. He later became a Spanish citizen. When Florida became part of the United States, he became an American citizen because of the Adams-Onis Treaty. He was the youngest son of Thomas Clarke, Sr., who was English, and Honoria Cummings, who was Irish. His parents were among the first British settlers in British East Florida. Records show he was born on October 12, 1774.

His father, Thomas Clarke, Sr., owned several pieces of land and houses in St. Augustine. In 1770, Governor James Grant gave him 300 acres of land near the Matanzas River. He named his farm "Worcester" after his hometown.

After his father died in 1780, his mother, Honoria, decided to stay in Florida. She became a Spanish citizen when Spain took control of Florida again in 1783. She had her children baptized in the Catholic church. Young George learned about business early. At age twelve, he started working for Panton, Leslie & Company, a British trading company that worked with Native Americans.

Life on the Matanzas River Plantation

Before 1802, George, who was now called "Jorge," helped his mother manage their property. By 1802, he was living in St. Augustine and serving in the city's army. In 1804, he bought land and buildings on Marine Street. He and his brother Charles then worked on their family's land by the Matanzas River. They cut down trees for timber and gathered oyster shells to make lime. They used flatboats to send the wood and lime to town. They supplied the government with materials for public buildings and whitewash for houses.

The brothers also grew crops like corn, peas, sweet potatoes, and pumpkins on their parts of the farm. They lived there for a few years. But as their businesses grew, especially with new chances for profit at the free port of Fernandina, they moved their families and enslaved people in 1808. They went to the growing community at the north end of Amelia Island. Four free workers were hired to work their land on the Matanzas River while they were away. In 1814, a census in Fernandina mentioned "Don Jorge Clarke," his partner Flora Leslie, and their four children, who were 7 to 15 years old.

George J. F. Clarke owned ten adult enslaved workers. Four were women, one of whom worked in his home. The other three were hired out as laundresses or house servants. The six men mostly worked in his timber business alongside rented enslaved people and free workers who earned wages. Clarke was one of the important citizens who had a family with different racial backgrounds. He lived with Flora Leslie, a woman he had freed. He made their eight children his heirs, sharing his property among them in his will. After Flora died, he had four more children with another woman named Anna or Hannah Benet. He left them and her 1,500 acres of land.

Serving Spanish East Florida

Clarke's first known public job, outside of the army, was as a temporary public surveyor. He likely worked as a deputy surveyor before this. The main surveyor, Juan Purcell, was away for a long time. So, on May 8, 1811, acting Governor Estrada made Clarke the Surveyor General of East Florida. Spain was busy with the Napoleonic invasion and had little control over Florida. Clarke was in charge of surveying land grants. He surveyed many land grants for free Black people and helped them keep these grants when the United States took over Florida in 1821. After the East Florida revolution in 1812, U.S. troops took over Fernandina. Spanish citizens, including Clarke, had to leave, and their homes and businesses were damaged.

The United States Congress passed the Embargo Act of 1807 and stopped importing enslaved people in 1808. That same year, Fernandina was declared a free port. It started shipping a lot of Florida cotton and lumber. It also became a place for smuggling. The town grew very quickly, with fancy houses and simple shacks built next to each other. Gardens were planted everywhere, and the streets were just winding paths. Governor White was worried about Fernandina's messy and unhealthy state. On May 10, 1811, he told Clarke to plan the town so that streets were straight and lots were even.

During the Patriot War of 1812, George J. F. Clarke and his brother Charles strongly opposed the American invaders. George was in charge of one of the two Spanish defenses at Fernandina. On March 14, his brother Charles reported that rebels were gathering to attack Fernandina.

On March 16, eight American gunboats, led by Commodore Hugh Campbell, lined up in the harbor and aimed their guns at the town. Clarke and George Atkinson were sent to meet Commodore Campbell and find out what he wanted. But Campbell was unsure. General George Mathews ordered his colonel to demand that Justo Lopez, the commander of Fort San Carlos and Amelia Island, surrender. Lopez agreed because the American force was stronger. He told Clarke to go to John H. McIntosh and Colonel Lodowick, who were leaders of the "Republic of Florida," with a flag of surrender. This meant giving the port and town to the Patriot forces. George, along with Justo Lopez, George Atkinson, and Charles W. Clarke, signed the surrender papers on March 17. American forces held Amelia Island for Spain until the next spring. They closed Fernandina harbor to foreign ships to stop the smuggling.

After the Patriot War, Clarke's main business was buying and selling land in Fernandina and other parts of Florida. He usually bought land or got it as a grant, then found buyers. Sometimes he worked as an agent, like when he helped sell Fort George island in 1816 to Zephaniah Kingsley.

Clarke's last job for Spain was as Deputy Governor of East Florida. The Spanish government in Florida had been unstable. This was partly due to events in Europe, like the Napoleonic invasion of Spain. Spain's money was gone, and its government was weak. Conditions in Florida were also unsettled with Native American uprisings, the Patriot War, and then the MacGregor invasion and Louis Aury's takeover. Spain's main worry was that the United States wanted to take over Florida.

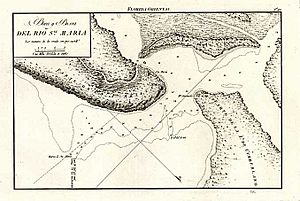

In May 1813, U.S. troops left Florida. Governor Kindelán gave local self-government to the people in the areas along the St. Johns and St. Marys rivers and Amelia Island. This was under the new Spanish Constitution of 1812. But it did little to stop the chaos in the area, especially around the St. Marys River, where the "Patriots" wanted to keep their "Republic of Florida." There were many civil problems, and the rebellion continued. In 1816, Governor Coppinger sent Clarke, Zephaniah Kingsley, and Henry Yonge, Jr. to talk with the unhappy people and make a deal for peace.

The three men met 40 people near the St. Marys River. They arranged a bigger meeting for the men of the region. Clarke and the others offered a "plan for peace and order." They suggested that the people accept Spanish rule under a plan that divided the area between the St. Marys and St. Johns into three self-governing districts. These were Upper St. Marys, Lower St. Marys, and Nassau (Amelia Island). Each district would have a court and its own local army, with officers chosen by the people. The group accepted these terms, and Clarke's plan was adopted.

Governor Coppinger approved these actions. He offered Clarke a job to oversee the new districts. Clarke accepted, but only for Upper and Lower St. Marys, not Amelia Island. Clarke was then named Capitan del partido Septentrional de la Florida del Esta (Captain of the Northern District of East Florida). His obituary called him "Lieutenant Governor of East Florida." He later wrote that during his five years in this job, there was only one appeal and one complaint sent to St. Augustine.

As "Captain" of the "Northern Division" and Lieutenant of the Urban Militia, Clarke helped Florida greatly during the MacGregor and Aury period. He was key in keeping his area loyal to Spain. He led three companies of soldiers, mostly Black citizens, called by the governor to defend Amelia Island.

The Spanish officer leading the expedition ordered a retreat, which disappointed Clarke's men. Even so, Clarke worked to stop the invaders from moving into Florida. He also tried to prevent the movement of enslaved people and other illegal goods to and from Fernandina.

Under Governor Coppinger's orders, Clarke explored Fernandina in August and September 1817. He reported on the enemy's soldiers, weak points in their forts, the number of ships in the harbor, and rumors of more troops coming. He also reported that the enemy planned to take enslaved people from nearby farms to fix the fort. Clarke told the governor that his soldiers were ready to fight.

In his report on September 1, Clarke said that MacGregor had left. He then suggested a plan for Spanish troops to attack the enemy forces still in Fernandina. After MacGregor left, the pirate Louis Aury took control of the island. He declared Florida part of the Republic of Mexico. On December 23, the United States government, which had been watching, moved in, and Aury surrendered. The American flag was raised over Fort San Carlos. This was the fifth flag in five years to fly over Fernandina. United States troops stayed on Amelia Island until November 30, 1819. Meanwhile, the U.S. and Spain finished their talks about the treaty to transfer Florida.

Clarke lived in Fernandina from 1808 until MacGregor took the town in 1817. He then moved to St. Marys, Georgia, and rented a house. One of his achievements was setting up regular mail service from that town through East Florida. Soon after, he became the Spanish vice consul for the Carolinas and Georgia. He held this job until Florida changed flags.

When the United States took control of Florida in 1821, Clarke's services were not needed. From 1823 to 1825, he often had to appear as a witness before the Board of Commissioners for East Florida. This board was set up to check and approve land claims from former Spanish citizens. The commissioners were Davis Floyd, William F. Blair, and Alexander Hamilton Jr.. Hamilton thought Clarke's claims were sometimes "extravagant" and "inconsistent." The commissioners were often doubtful of Clarke's surveys, which were sometimes messy or incomplete. They usually rejected claims that had no other proof.

Later Life and Contributions

Clarke was living in St. Marys, Georgia, when Florida became part of the United States. But he returned to St. Augustine before the spring of 1823. With the change of flags, Clarke's public service mostly ended. He spent the rest of his life in St. Augustine. He focused on taking care of his properties, trying new things in farming and fruit growing, and writing articles for the East Florida Herald newspaper. He also tried to get money from the U.S. government for properties he lost during the Patriot War.

Local farmer Gen. Joseph M. Hernández mentioned Clarke's gardening work in a speech to the Agricultural Society of St. Augustine. He said that Clarke and Col. Murat had brought many valuable plants from northern states. He noted that both were doing experiments that could be very important for the area.

Clarke wrote many articles for the St. Augustine newspaper, the East Florida Herald, from 1823 to 1832. He shared what he learned from his gardening observations and experiments. He talked about using fertilizers correctly, growing fruits, vegetables, and tobacco, keeping bees, using wild plants, and the need to grow different kinds of crops. He believed in self-sufficient farming. He also thought sweet oranges should be grown more than sour ones. He said that unused lands could be made profitable by planting fruit trees. In a letter from August 10, 1830, he described how Jesse Fish carefully picked and handled oranges from his farm. These oranges were shipped safely to London and were liked for their sweetness. He strongly believed that people in Florida should grow more vegetables. He also thought growing maguey for making drinks would be profitable.

He wrote a long article about growing and preparing tobacco for cigars. He also discussed how the roots of "comtee" (coontie), a wild plant in Florida and Georgia, could be used to make a starchy flour called Florida arrowroot. This idea came true later as a business in Florida.

Death and Burial

About four years before he died, Clarke published his thoughts on education. After his death, the East Florida Herald published a letter from Clarke in seven parts. This letter was written to Rev. Jedidiah Morse on July 1, 1822, from St. Marys. It talked about the Florida Native Americans: their traits, customs, language, looks, use of plants for medicine, spiritual beliefs, burial methods, practice of slavery, how they treated enemies, and about chiefs Secoffee (Cowkeeper) and his son King Payne. Clarke said he got much of his information from a Native American woman named 'Mary,' who he said died in 1802 at age 100.

The exact date of Clarke's death is not certain, and no one knows where he is buried.

Records from the Cathedral archives for 1831–1844 are missing. But according to Louise Biles Hill, October 20, 1836, is most likely the correct date. Clarke was probably buried in St. Augustine in the Tolomato Catholic cemetery. This cemetery is now on Cordova street. However, no graves or headstones with his name have been found there. There is also no record of his burial in the Bosque Bello cemetery in Old Town Fernandina.

| William L. Dawson |

| W. E. B. Du Bois |

| Harry Belafonte |