Patriot War (Florida) facts for kids

The Patriot War was a secret plan in 1812 to take over Spanish East Florida and add it to the United States. This invasion and takeover of parts of East Florida was a bit like a private military adventure, but it also had support from the United States Army, Navy, and Marines. Even soldiers from Georgia and Tennessee helped out.

The idea for this rebellion came from General George Mathews. He was asked by U.S. President James Madison to accept any offer from local leaders to hand over parts of Florida to the U.S. President Madison also wanted to stop Great Britain from taking over Florida. The rebellion was supported by the "Patriot Army," mostly made up of people from Georgia.

With help from U.S. Navy gunboats, the Patriot Army took over Fernandina and parts of northeast Florida. However, they never became strong enough to attack St. Augustine. Later, U.S. Army troops and Marines were sent to Florida to help the Patriots. The U.S. occupation of parts of Florida lasted over a year. But after the U.S. military left and Seminole Native Americans joined the fight, the Patriots gave up.

Contents

Why the War Happened

Early Conflicts Over Florida

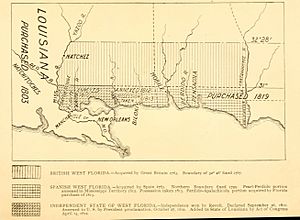

The United States and Spain had disagreements about East and West Florida even during the American Revolutionary War. American leaders hoped that all of British North America, including Florida, would become part of the U.S. But both Floridas became safe places for people loyal to Britain during the Revolution.

Spain joined France in the war to help the U.S. against Britain in 1779. Spain wanted to get Florida back and control the Mississippi River. The U.S. wanted all the land east of the Mississippi River, including Florida, and to use the Mississippi freely.

The 1783 Treaty of Paris ended the American Revolutionary War. It gave Florida back to Spain. Most British people in Florida left after this, many going to the Bahamas. Spain disagreed with parts of the treaty, closing the Mississippi to American ships in 1784. Spain also claimed larger boundaries for West Florida than the treaty stated.

Other problems between the U.S. and Spain included Florida and Louisiana welcoming American settlers. Spain also supported Native American tribes in the U.S. Finally, in 1795, the U.S. and Spain signed Pinckney's Treaty. This treaty set the boundary between the U.S. and West Florida at the 31st parallel. Spain also allowed the U.S. to use the Mississippi River and store goods in New Orleans.

In 1800, France got Louisiana back from Spain. The agreement was unclear about the exact size of Louisiana. Before 1763, France had claimed the entire Gulf of Mexico coast from the Perdido River to the Rio Grande as part of Louisiana. France wanted the area between New Orleans and Mobile Bay to be included when Louisiana was returned. France also wanted to get East Florida from Spain.

After the Louisiana Purchase

The U.S. wanted a port on the Gulf of Mexico that Americans could easily use. So, in 1803, U.S. diplomats tried to buy the Isle of Orleans and West Florida from France. When Robert Livingston asked France about buying the Isle of Orleans, France offered to sell all of Louisiana.

Even though buying all of Louisiana was more than they were told to do, Livingston and James Monroe believed the deal included the area east of the Mississippi to the Perdido River. President Thomas Jefferson later agreed, thinking the Louisiana Purchase gave the U.S. a strong claim to West Florida.

Spain disagreed that West Florida was part of the Louisiana Purchase. In 1804, the U.S. dropped plans to build a customs house at Mobile Bay because of Spain's protests. However, the U.S. still believed its claims were right. The U.S. also hoped to get all of the Gulf coast east of Louisiana. They planned to offer to buy the rest of West Florida and all of East Florida.

Later, the U.S. decided to offer to pay off Spain's debts to American citizens instead of buying the colonies. The U.S. argued that it was taking a claim on East Florida to settle these debts.

In 1808, Napoleon invaded Spain and forced King Ferdinand VII to step down. Napoleon put his brother Joseph Bonaparte on the Spanish throne. Spanish people fought back against the French invasion and formed a government. This government then allied with Great Britain against France. This alliance worried the U.S. because they feared Britain might set up bases or take over Spanish colonies like Florida. This would be a big threat to the southern U.S. border.

West Florida's Independence

By 1810, during the Peninsular War in Europe, the French army had largely taken over Spain. Rebellions against Spanish rule broke out in many of Spain's American colonies. In the western part of West Florida, settlers met in Baton Rouge in the summer of 1810. They wanted to keep order and prevent French control. At first, they tried to create a local government loyal to the Spanish king.

But after finding out that the Spanish governor had asked for military help to stop an "uprising," the local militia took over the Spanish fort in Baton Rouge. On September 26, the convention declared West Florida independent.

The leaders of this new republic asked the U.S. to take over the area and provide money. On October 27, 1810, President James Madison announced that the area was now part of the U.S. because of the Louisiana Purchase. He said the U.S. had waited to remove Spanish officials peacefully. At the same time, Governor William C. C. Claiborne of the Territory of Orleans was told to occupy the area and govern it.

Settlers in West Florida and the nearby Mississippi Territory also started organizing in the summer of 1810. They wanted to seize Mobile and Pensacola, even though Pensacola was outside the area the U.S. claimed. U.S. officials stopped these unauthorized military actions. The Spanish governor of West Florida, Juan Vicente Folch y Jaun, hoped to avoid fighting. He removed customs duties on American goods at Mobile. He also offered to surrender all of West Florida to the U.S. if he didn't get help or orders from Havana by the end of the year.

Secret Agents and Plans

U.S. officials were worried that France would take over all of Spain. This could mean that Spanish colonies would fall under French control or be seized by Great Britain. On June 20, 1810, Secretary of State Robert Smith wrote to Georgia Senator William H. Crawford. He asked Crawford to find someone to go to East Florida. This person would gather information and spread the word that if settlers rebelled against Spain, they would be welcomed into the U.S. Crawford chose General George Mathews for this job.

In January 1811, President Madison asked Congress to pass a law. This law would let the U.S. "temporarily possess" any land next to the U.S. east of the Perdido River. This included the rest of West Florida and all of East Florida. The U.S. would be allowed to accept land from "local authorities" or occupy it to stop any foreign power other than Spain from taking it. The law also set aside $100,000 for "expenses as the President shall deem necessary." Congress passed this secret law on January 15, 1811.

Under this law, General Mathews and Colonel John McKee were given special tasks. They were asked to help bring Florida under U.S. control. George Mathews was a hero from the Revolutionary War and a former Governor of Georgia. Colonel John McKee was a soldier and a U.S. agent to the Choctaw Native Americans. He also carried letters between Governor Folch and the U.S. government.

During his trips in East Florida, Mathews tried to see if settlers wanted to break away from Spain. He secretly met with five important East Florida settlers. These men had military and money influence in the area. Mathews believed these meetings showed that settlers in East Florida would rather join the U.S. than be ruled by Britain or Napoleon.

One of these five men was John Houston McIntosh. He was a rich landowner and later a leader of the rebel Patriot group. McIntosh and other southerners were very worried that Spanish Florida was a safe place for runaway enslaved people. He believed that Florida needed to be taken over to prevent this.

In September 1811, the British ambassador in Washington, Augustus Foster, wrote to President Madison's cabinet. He protested American actions in East Florida. He wanted an explanation for Mathews' actions against the Spanish government. Secretary of State James Monroe replied two months later. Monroe said the U.S. could not allow East Florida to fall into the hands of another country. He did not mention General Mathews at all in his letter.

When the newspapers published the letters between Monroe and Foster, Mathews took Monroe's words as approval. He began to gather a group of soldiers to attack Spanish Florida. This group called themselves the Patriots.

The Patriots Take Fernandina

Even before Mathews formed his Patriot group, there were signs of trouble in East Florida. In early January 1811, a letter from George J. F. Clarke, a Spanish official, described "invaders" from Georgia. They had crossed the border and camped near Fernandina. Their goal was to cause problems in the region.

It was discovered that these invaders were working for Major Lt. Col. Thomas Adam Smith. He was the U.S. officer in charge at Point Peter, a military post in Georgia near Amelia Island, Florida. It was openly admitted that they were working with the Patriots and were part of Mathews' plans for Florida. This direct link between the U.S. military and the Patriots showed early U.S. intentions in the area.

In the summer of 1811, Mathews met with John Houston McIntosh. They discussed a plan to set up a temporary local government in Spanish Florida. This temporary government would then transfer its land to the United States. This way, the U.S. could gain parts of East Florida without appearing to directly attack Spain.

To hide their true intentions, and because few Floridians wanted to rebel, Mathews mostly recruited soldiers from north of the St. Mary's River. This kept the Spanish government in St. Augustine from knowing about the growing threat. Many of the men were volunteers from Camden County, Georgia and soldiers from General John Floyd's militia.

By early March 1812, the group had about 125 men. Besides the Georgian volunteers, there were also some men from Tennessee and possibly a few Spanish soldiers who had left their army. This group called themselves the Patriots.

To make his force stronger, Mathews planned for U.S. troops at the Florida/Georgia border to join the Patriots. Mathews would then forgive these soldiers for leaving their posts and give them back their military rank after the rebellion. These troops were from the garrison at Point Peter. They were under the temporary command of Major Jacint Laval while their commanding Colonel Thomas A. Smith was away. Laval and Mathews did not get along, and Laval refused to give Mathews troops or weapons.

It wasn't until March 16 that Colonel Smith returned to Point Peter. He agreed to provide Mathews with what he asked for. The next day, 50 soldiers joined the Patriots to march on Fernandina. On that same day, March 16, the Patriots chose John Houston McIntosh as their leader.

Mathews also asked the Navy for help. He sent a request to Commodore Hugh G. Campbell, who commanded the naval forces at St. Mary's. Mathews asked for weapons and help from gunboats. Campbell said he never agreed with Mathews' mission and that his ships had no orders to fire. However, five gunboats did anchor on the St. Mary's River and aimed their guns at the city while the Patriot group captured Fernandina on March 17, 1812.

A Temporary Government

On March 17, 1812, the same day the Patriots marched into Fernandina, they took down the Spanish flag and raised the Patriot flag. One of the Patriot officers gave a speech offering the town to the U.S. Colonel Smith, who was there, accepted the land for the U.S. and promised to protect the city.

The officer's speech was part of a treaty between the Spanish and Mathews. The treaty had six articles. Besides the promise that the U.S. would govern and "protect" Fernandina, it also said the U.S. would respect existing Spanish land grants. It also offered jobs in the U.S. army to any Spanish soldiers who wanted to switch sides. The agreement also stated that East Florida's ports would remain open to Great Britain until at least May 1813. This was likely done to keep local merchants and plantation owners happy, as their income depended heavily on trade with England.

In the following weeks, the Patriot group marched towards St. Augustine. Colonel Smith and his soldiers followed behind. At each town they stopped at, they repeated what they did in Fernandina. They would take the place in the Patriot's name and then immediately hand the land over to the U.S. By late March or early April, Mathews and his group had captured Fort Mose, just outside St. Augustine, and set up their headquarters there.

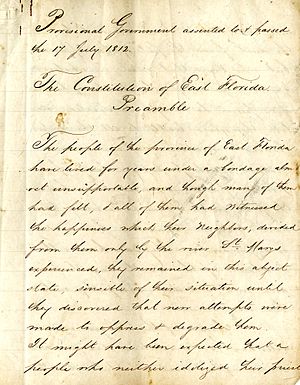

On July 17, 1812, the temporary government published a constitution. Fourteen members of the Patriot group signed it, with John Houston McIntosh as President.

In January 1814, a group of soldier-settlers built a two-story blockhouse and named it Fort Mitchell. Historians today are not sure exactly where Fort Mitchell was located. It was probably in Alachua County, possibly near the modern town of Micanopy.

General Buckner F. Harris declared Fort Mitchell to be the capital of the Republic of East Florida. After building the fort, they sent a request to the U.S. Congress. They asked to add the "District of Elotchaway [Alachua] in the Republic of East Florida" as a territory to the U.S. They also offered to send soldiers to fight the British, as the War of 1812 was happening at the time.

Besides building the fort, Harris also took farmland from nearby Paynes Prairie. The Patriots wanted this land because of its rich soil. However, the capital did not last long. The fort was abandoned by May 1814 after General Buckner Harris was killed by Seminole Native Americans.