St. Johns River facts for kids

Quick facts for kids St. Johns River |

|

|---|---|

St. Johns River near Astor

|

|

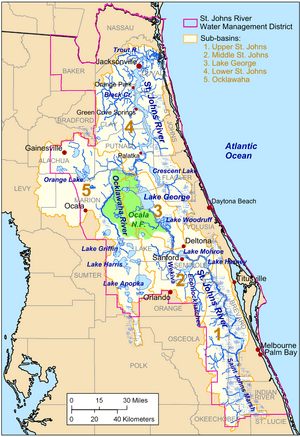

St. Johns River surrounding with corresponding watersheds designated by the St. Johns River Water Management District: 1. Upper basin, 2. Middle basin, 3. Lake George basin, 4. Lower basin, 5. Ocklawaha River basin

|

|

| Country | United States |

| State | Florida |

| Cities | Sanford, DeBary, Deltona, DeLand, Palatka, Green Cove Springs, Orange Park, Jacksonville |

| Physical characteristics | |

| Main source | St. Johns Marsh near Vero Beach, Indian River County, Florida 30 ft (9.1 m) 27°57′18″N 80°47′3″W / 27.95500°N 80.78417°W |

| River mouth | Atlantic Ocean Jacksonville, Duval County, Florida 0 ft (0 m) 30°24′05″N 81°24′3″W / 30.40139°N 81.40083°W |

| Length | 310 mi (500 km) |

| Basin features | |

| Basin size | 8,840 sq mi (22,900 km2) |

| Tributaries |

|

The St. Johns River (Spanish: Río San Juan) is the longest river in the state of Florida, USA. It's very important for both business and fun activities. The river is about 310 miles (500 km) long. It flows north and goes through or borders 12 counties.

The St. Johns River doesn't drop much in height from where it starts to where it ends. It's less than 30 feet (9 m)! This means it flows very slowly, about 0.3 mph (0.13 m/s). People often call it "lazy" because of this.

Many lakes are connected to the river or flow into it. At its widest, the river is almost 3 miles (5 km) across. But at its start, it's a narrow, marshy area in Indian River County that boats can't use. The St. Johns drainage basin (the area of land where water drains into the river) is huge, about 8,840 square miles (22,900 km2). It includes many of Florida's important wetlands.

The river is divided into three main parts, called basins. It also has two other areas that feed into it: Lake George and the Ocklawaha River. All these areas are managed by the St. Johns River Water Management District.

Florida was one of the first places in the United States where Europeans settled. But much of Florida stayed wild until the 1900s. As more people moved in, the St. Johns River, like many other Florida rivers, was changed. People built farms and towns, which led to pollution and changes in the river's path. This harmed its ecosystem (all the living things and their environment).

In 1998, the St. Johns was named one of 14 American Heritage Rivers. But in 2008, it was listed as the 6th most endangered river in America. Now, people are working hard to restore the river and its surrounding areas as Florida's population keeps growing.

Many different groups of people have lived near the St. Johns River throughout history. These include early Native American groups like the Paleo-indians and Timucua, as well as French, Spanish, and British colonists. Later, Seminoles, freed slaves, and early Florida settlers lived there. More recently, land developers, tourists, and retirees have made their homes along the river.

The St. Johns River has been written about by famous authors like William Bartram, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings. In the year 2000, about 3.5 million people lived in the areas that drain into the St. Johns River.

Contents

River's Journey: Where it Starts and Flows

The St. Johns River is Florida's main waterway for business and fun. It starts in Brevard County and flows north to the Atlantic Ocean in Duval County. The river begins in a very flat area, only about 30 feet (9.1 m) above sea level. Because it's so flat, the river has a long "backwater" area. Its water levels go up and down with the ocean tides. Interestingly, it's in the same type of land as the Kissimmee River, but the Kissimmee flows south!

Upper Basin: The River's Beginning

The St. Johns River is divided into three main sections, or basins. Since the river flows north, the "upper basin" is actually at its southernmost point. The river starts as a group of marshes in Indian River County. This area, west of Vero Beach, is called the St. Johns Marsh.

The river here is a "blackwater stream." This means it gets most of its water from swamps and marshes. Water slowly seeps through the sandy soil and gathers in a slight valley. The upper basin covers about 2,000 square miles (5,200 km2). The St. Johns becomes wide enough for boats in Brevard County. It then touches the edges of Osceola and Orange Counties. It also flows through the southeast part of Seminole County before becoming the middle basin.

In the 1920s, the upper basin's water levels were lowered a lot by the Melbourne Tillman drainage project. This project dug canals to send water eastward to the Indian River. But in 2016, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers finished a project to bring back the natural water flow to much of this area.

The river is narrowest and hardest to navigate in this part. Boat paths are often unclear. The best way to travel here is by airboat. There are about 3,500 shallow lakes in this area, usually 3 and 10 feet (1 and 3 m) deep. The river flows into many of these lakes, making navigation tricky.

One of the first lakes is called Lake Hell 'n Blazes. Its name comes from frustrated boatmen in the 1800s. They would yell when trying to get through floating islands of plants that moved with the slow current. Other lakes in this area include Washington, Winder, and Poinsett. The northern part of the upper basin has the Tosohatchee Wildlife Management Area. This area was created in 1977 to help filter water flowing downstream.

The wetlands in the upper and middle basins get their water from rainwater. This water is held by the shape of the land around them. These areas don't have much oxygen or nutrients. Plants often grow in peat, which is made from old, decaying plants. Water levels change a lot with Florida's wet and dry seasons. Plants here must be able to handle both floods and droughts.

Trees like sweetbay (Magnolia virginiana), cypress (Taxodium), and swamp tupelo (Nyssa biflora) grow well on slightly raised land called hammocks. Trees that live in water for a long time often have wide trunks, tangled roots, or cypress knees to get oxygen. But most of the plant life here is aquatic. Common wetland plants include the American white waterlily (Nymphaea odorata), pitcher plants, and Virginia iris (Iris virginica). In the southernmost parts of the river, Cladium, or sawgrass, grows in huge wet prairies. These wetland plants are great at filtering out pollution before it reaches the river.

Middle Basin: Springs and Cities

For about 37 miles (60 km), the river flows through a 1,200-square-mile (3,100 km2) basin. This area gets its water mainly from springs and stormwater runoff. This basin covers Orange, Lake, Volusia, and Seminole Counties. It's home to the greater Orlando area, where two million people live and major tourist spots are located.

The river here sometimes has clear banks and sometimes flows into wide, shallow lakes. Two of the biggest lakes in the middle basin are formed by the river: Lake Harney and Lake Monroe. Lake Harney is shallow, about 9-square-mile (23 km2). It's fed by the narrow Puzzle Lake. Just north of it, the Econlockhatchee River joins the St. Johns, making it easier for larger boats to navigate.

The river then turns west, touching Lake Jesup before flowing into Lake Monroe near Sanford. This is where the St. Johns becomes a main shipping route. The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers keeps the channel deep, and the U.S. Coast Guard marks the way. Lake Monroe is a large lake, about 15 square miles (39 km2), with an average depth of 8 feet (2.4 m).

After Lake Monroe, the St. Johns is usually about 8-foot (2.4 m) deep and 100 yards (91 m) wide. It meets its most important tributary (a river or stream flowing into a larger river), the Wekiva River. The Wekiva is fed by springs and adds about 42,000,000 US gallons (160,000,000 L) of water to the St. Johns every day.

Forests around the Wekiva River are home to Florida's largest group of black bears (Ursus americanus floridanus). Several groups of Rhesus monkeys (Macaca mulatta) also live near the river. No one is sure how the monkeys got to Florida. Some say they were brought for Tarzan movies filmed near the Silver River in the 1930s. Others say they were for "jungle cruises" offered by a boat operator around the same time.

Florida's springs stay at a constant temperature of 72 °F (22 °C) all year. Because of this, Blue Spring is a winter home for West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris). They are protected within Blue Spring State Park. Manatees are big, slow-moving plant-eating water mammals. Their biggest dangers are human development and fast-moving boats. Many parts of the St. Johns and its smaller rivers are "no-wake zones" to protect manatees from boat propellers. People are not allowed to interact with manatees in Blue Spring State Park.

Small water animals, called invertebrates, are super important in marshes. They are the base of the food webs. Animals like apple snails (Pomacea paludosa), crayfish, and grass shrimp eat plants. This helps plants break down and provides food for fish and birds. Insect larvae use the water to grow. They eat tiny copepods and amphipods that live in microscopic algae.

Mosquitos, which are born in water, are a favorite food for 112 types of dragonflies and 44 types of damselflies in Florida. These animals are tough and can handle changes in water levels, like dry spells or floods.

Many kinds of vertebrates (animals with backbones) live in the marsh waters. These include frogs, salamanders, snakes, turtles, and alligators (Alligator mississippiensis). Most of these animals are active at night. Frog calls can be very loud, and during alligator mating season, the grunts of male alligators join in.

River otters (Lutra canadensis) live along the entire St. Johns River and its smaller streams. They live in burrows or in tree roots near the water. They eat crayfish, turtles, and small fish. Otters are usually active at night, playful but shy of people. The marshes around the upper basin are full of birds. A recent study counted 60,000 birds in one month, either nesting or feeding there.

Wading birds and water birds like the white ibis (Eudocimus albus), wood stork (Mycteria americana), and purple gallinule (Porphyrio martinicus) need the water to raise their young. They hunt small fish and tadpoles in shallow water during the dry season. In good years, their colonies can have thousands of birds. They make a lot of noise and help fertilize trees with their droppings.

- Birds found in the middle and upper St. Johns River basins

-

American white ibis (Eudocimus albus)

-

Barred owl (Strix varia)

-

Wood stork (Mycteria americana)

-

Limpkin (Aramus guarauna)

-

American black vulture (Coragyps atratus)

-

Yellow-crowned night heron (N. violacea)

-

Red-shouldered hawk (Buteo lineatus)

-

Anhinga (Anhinga anhinga)

Lake George: A Big Lake on the River

The river turns north again as it flows through a 46,000-acre (190 km2) area. This basin spreads across Putnam, Lake, and Marion Counties, and western Volusia County. Just north of the Wekiva River is Blue Spring. This is the biggest spring on the St. Johns, producing over 64,000,000 US gallons (240,000,000 L) of water every day.

Florida springs stay at a cool 72 °F (22 °C) all year. This makes Blue Spring a perfect winter home for West Indian manatees (Trichechus manatus latirostris). They are protected within Blue Spring State Park. Manatees are large, slow-moving animals that eat plants. Their main dangers are human development and getting hit by fast boats. Many parts of the St. Johns and its smaller rivers are "no-wake zones" to keep manatees safe. People are not allowed to interact with manatees in Blue Spring State Park.

Next to Blue Spring State Park is Hontoon Island State Park, which you can only reach by boat. In 1955, a very rare Timucua totem (a carved symbol) shaped like an owl was found buried in the St. Johns muck near Hontoon Island. This figure might mean its creators were part of the owl clan. Two more totems, shaped like a pelican and an otter, were found in 1978. These are the only totems found in North America outside of the Pacific Northwest.

The St. Johns River flows into the southern part of Lake George. This is Florida's second largest lake, covering 72 square miles (190 km2). It's about 6 miles (9.7 km) wide and 12 miles (19 km) long. The land around Lake George covers 3,590 square miles (9,300 km2). This area includes Ocala National Forest and Lake George State Forest. These forests protect an ecosystem with lots of pine trees and scrub.

Flatwoods forests are common in the Lake George area. They have slash pines (Pinus elliottii), saw palmetto (Serenoa repens), and over 100 types of ground plants. These plants grow in poor, sandy soil. Flatwoods pine forests are usually dry but can handle short floods. Larger animals like wild turkeys (Meleagris gallopavo), sandhill cranes (Grus canadensis), and the largest group of southern bald eagles (Haliaeetus leucocephalus leucocephalus) in the U.S. live here. Mammals like raccoons (Procyon lotor), opossums (Didelphis virginiana), bobcats (Lynx rufus), and white-tailed deer (Odocoileus virginianus) also prefer these dry, flat areas with good cover and places to nest.

Ocklawaha River: A Major Branch

The Ocklawaha River flows north and joins the St. Johns. It's the largest river that flows into the St. Johns and has a lot of history. The Ocklawaha's drainage basin covers Orange, Lake, Marion, and Alachua Counties, totaling 2,769 square miles (7,170 km2). Cities like Ocala, Gainesville, and the northern parts of Orlando are in this basin.

The Ocklawaha River has two starting points. One is a chain of lakes, with Lake Apopka in Lake County being the largest. The other is the Green Swamp near Haines City in Polk County, which is drained by the Palatlakaha River. The Silver River, fed by one of Florida's most active springs (releasing 54,000,000 US gallons (200,000,000 L) daily), joins the Ocklawaha about halfway along its 96-mile (154 km) length.

The St. Johns River is home to 183 types of fish, with 55 found in the main part of the river. Fishermen love central Florida for its many largemouth bass (Micropterus salmoides), black crappie (Pomoxis nigromaculatus), and bluegill (Lepomis macrochirus). One fish, the southern tessellated darter (Etheostoma olmstedi), is found only in the Ocklawaha.

Some marine (ocean) fish also live in the St. Johns. They either swim upriver to lay eggs or find salty spring-fed areas. For example, a group of Atlantic stingrays (Dasyatis sabina) lives in Lake Washington in the upper basin. Ocean worms, snails, and white-fingered mud crabs (Rhithropanopeus harrisii) have also been found far upriver where tides don't usually reach.

On the other hand, American eels (Anguilla rostrata) live in the St. Johns and Ocklawaha. But they travel all the way to the Sargasso Sea in the middle of the Atlantic Ocean to lay their eggs. After living in the ocean for a year, many eels find their way back to the St. Johns to live. Then, guided by the moon, they make the long journey back to the Sargasso Sea to lay eggs and then die.

Lower Basin: The River Meets the Ocean

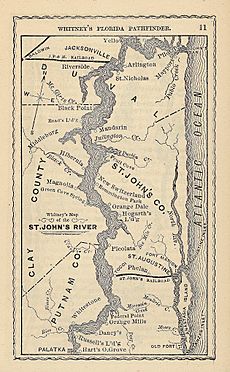

From where the Ocklawaha River joins, the St. Johns flows 101 miles (163 km) to the Atlantic Ocean. This lower basin drains 2,600 square miles (6,700 km2) in Putnam, St. Johns, Clay, and Duval Counties. Twelve smaller rivers and streams flow into the St. Johns in this area.

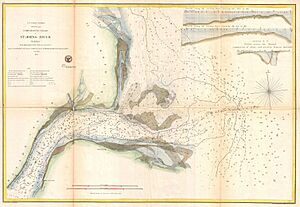

The river gets much wider north of Lake George. Between Lake George and Palatka, it's between 600 and 2,640 feet (180 and 800 m) wide. Between Palatka and Jacksonville, it widens even more, to between 1 and 3 miles (1.6 and 4.8 km). This part of the river is the easiest to navigate, and shipping is its main use. The Army Corps of Engineers keeps shipping channels at least 12 feet (3.7 m) deep and 100 feet (30 m) wide. North of Jacksonville, the channels are even bigger: 40 feet (12 m) deep and between 400 and 900 feet (120 and 270 m) wide.

The towns and cities along the lower part of the river are some of Florida's oldest. Their history is closely tied to the river. Both Palatka and Green Cove Springs were popular tourist spots in the past. Many smaller towns grew up around ferry crossings. But when railroads and later Interstate highways were built closer to the Atlantic Coast, many of these towns saw their economies decline, and the ferry crossings were forgotten.

The last 35 miles (56 km) of the river flows through Jacksonville, a city with over a million people. Much of Jacksonville's economy depends on the river. About 18,000,000 short tons (16,000,000 t) of goods are shipped in and out of Jacksonville each year. Exports include paper, phosphate, fertilizers, and citrus. Major imports include oil, coffee, limestone, cars, and lumber. The Port of Jacksonville brings in $1.38 billion to the local economy and supports 10,000 jobs.

The U.S. Navy has two bases in the Jacksonville area. Naval Station Mayport, at the river's mouth, is the second largest Atlantic Fleet operation and home port in the country. Naval Air Station Jacksonville is one of the Navy's biggest air bases. It's home to two air wings and over 150 aircraft.

Jacksonville is often called "The River City" because its culture is centered on the St. Johns. An annual footrace called the Gate River Run has 18,000 participants who run along and over the river twice. The largest kingfishing tournament in the U.S. is held on a St. Johns tributary. Sport fishers try to catch king mackerel (Scomberomorus cavalla), cobia (Rachycentron canadensis), dolphin (Corypha hippurus) and Wahoo (Acanthocybium solandri). The home stadium for the Jacksonville Jaguars football team faces the river, as does most of downtown Jacksonville. Seven bridges cross the St. Johns in Jacksonville. All of them allow tall ships to pass, though some have restricted times during heavy traffic.

Tides cause ocean water to enter the St. Johns River's mouth. This can affect the river's level all the way into the middle basin. So, much of the river in Jacksonville is part seawater, creating an estuarine ecosystem. Animals and plants in these areas can live in both fresh and salt water. They can also handle changes in saltiness and temperature from tides and heavy rain. Marine animals like dolphins and sharks are sometimes seen in the St. Johns in Jacksonville, as are manatees. Fish like mullet (Mullidae), flounder (Paralichthys lethostigma), shad (Alosa sapidissima), and blue crabs (Callinectes sapidus) travel from the ocean to freshwater springs upriver to lay eggs.

While tiny freshwater invertebrates form the base of food webs in the middle and upper river, zooplankton and phytoplankton do this job in the salty estuary. Mollusks gather in large numbers at the St. Johns estuary. They feed on the bottom of the river and ocean floors. The importance of oysters (Crassostrea virginica) is clear from the many huge shell mounds left by the Timucua people. Oysters and other mollusks are a main food source for shorebirds. The large trees that line the river from its start to south of Jacksonville begin to change into salt marshes east of the city. Mayport is home to about 20 shrimping boats that use the St. Johns' mouth to reach the Atlantic Ocean.

How the River Formed and Its Water Works

Geologic History: How Florida Was Made

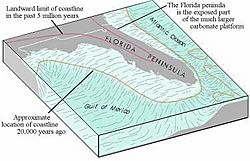

The St. Johns River flows through a coastal plain. This area was once made up of barrier islands, coastal sand dunes, and estuary marshes. The Florida Peninsula was mostly formed by ocean forces and minerals. It's so low that even small changes in sea levels can greatly affect its shape.

Florida was once part of a huge ancient continent called Gondwana. Underneath the rocks we see today is a base of igneous granite and volcanic rock. On top of this is a layer of sedimentary rock formed between 542 and 251 million years ago. During the Cretaceous period (145 to 66 million years ago), more layers of calcium carbonate and minerals from evaporated water (called evaporites) covered this base.

What we see on the peninsula today is a mix of sand, shells, and coral deposits, along with erosion from water and weather. The ocean has covered Florida at least seven times. Waves pressed sands, calcium carbonate, and shells into limestone. At the ocean's edge, beach ridges were formed by these deposits. Rivers that flow north-south, like the St. Johns, were created by these old beach ridges, which were often separated by low areas called swales. As the ocean water pulled back, lagoons formed in these swales. Acidic water then eroded them further. Also, barrier islands formed along the Atlantic Coast, creating a freshwater river by surrounding the lagoon with land.

From its start to about the Sanford area, the St. Johns flows north. Near Sanford, it takes a sharp turn west for a few miles. This is called the St. Johns River offset. But it soon turns north again. Geologists think this west-flowing part might have formed earlier than the north-flowing parts, perhaps millions of years ago. Some cracks and breaks in the earth's crust might also be responsible for this offset. While Florida doesn't have many earthquakes, a few small ones have happened near the St. Johns River.

Springs and Aquifers: Water Underground

All of Florida's fresh water comes from rain. This rain either flows into lakes and rivers or goes back into the air through evapotranspiration (evaporation and water released by plants). A lot of fresh water is also stored underground in aquifers.

There's a shallow surficial aquifer made of clay, shells, and sand. Below it is a denser layer. Wells are drilled into the shallow aquifer, which provides good quality water. Sometimes, the dense layer has cracks, allowing water to seep down and refill the deeper aquifer. The Floridan Aquifer, which is under the dense layer, is found under the entire state of Florida and parts of other states. It's easy to reach in northern Florida and provides fresh water for cities like St. Petersburg and Jacksonville.

Acidic rainwater slowly wears away the limestone, creating underground caverns. If the ground above these caverns is thin (less than 100 feet (30 m)), sinkholes can form. When the limestone or sand/clay above the aquifer dissolves and water pressure pushes out, springs form. The upper and middle basins of the St. Johns River are in an area where the aquifer system is close to the surface, so there are many springs and sinkholes.

Springs are measured by how much water they release. This depends on the season and rainfall. The biggest springs, called "first magnitude" springs, release at least 100 cubic feet (2.8 m3) of water per second. Four first magnitude springs feed the St. Johns River:

- Silver Springs in Marion County: 250 and 1,290 cubic feet per second (7.1 and 36.5 m3/s)

- Silver Glen Spring in Marion and Lake Counties: 38 and 245 cubic feet per second (1.1 and 6.9 m3/s)

- Alexander Springs in Lake County: 56 and 202 cubic feet per second (1.6 and 5.7 m3/s)

- Blue Spring in Volusia County: 87 and 218 cubic feet per second (2.5 and 6.2 m3/s)

Rainfall and Climate: Florida's Weather

The St. Johns River is in a humid subtropical climate zone. In summer, temperatures are usually between 74 and 92 °F (23 and 33 °C). In winter, they are between 50 and 72 °F (10 and 22 °C), though it can drop below freezing about a dozen times. The river's water temperature usually matches the air temperature, ranging from 50 and 95 °F (10 and 35 °C).

Where the river widens between Palatka and Jacksonville, wind can make boating tricky. You might see whitecap waves or very calm water.

Rain falls more often in late summer and early fall. Tropical storms and "nor'easters" (storms from the northeast) are common along Florida's Atlantic coast. The St. Johns River is 10 and 30 miles (16 and 48 km) inland. So, any storm hitting the counties from Indian River north to Duval will cause rain that drains into the St. Johns.

For example, Tropical Storm Fay in 2008 dropped 16 inches (410 mm) of rain in five days, mostly near Melbourne. The St. Johns near Geneva in Seminole County rose 7 feet (2.1 m) in four days, which was a record. The river near Sanford rose 3 feet (1 m) in 36 hours. Fay caused serious flooding in the middle basin because of the heavy rain and the river's flat slopes.

Usually, the St. Johns basin gets between 50 and 54 inches (1,300 and 1,400 mm) of rain each year, with half of it in the summer. The amount of water that goes back into the air through evapotranspiration is similar, between 27 and 57 inches (690 and 1,450 mm) a year, mostly in the summer.

Flow Rates and Water Quality

The entire river is in a very flat area, so it only drops about 0.8 inches (2.0 cm) per mile (km). It's one of the flattest major rivers on the continent. Because it's so close to the ocean in its lower part, its water levels and saltiness are affected by tides. Tides regularly change water levels as far south as Lake George. With strong winds, tidal effects can reach Lake Monroe, 161 miles (259 km) away, and sometimes even Lake Harney.

Tides usually raise the river level about 1.2 feet (0.37 m) at Jacksonville. This decreases to 0.7 feet (0.21 m) at Orange Park where the river widens. Then it increases back to 1.2 feet (0.37 m) at Palatka as it narrows. Because of tides, measuring how much water flows out in the lower basin can be tricky.

However, the estimated flow rate between the Ocklawaha River and central Jacksonville is between 4,000 to 8,300 cubic feet (110 to 240 m3) per second. At the mouth of the river at Mayport, the average flow without tides is 15,000 cubic feet (420 m3) per second. But with tides, it can go over 50,000 cubic feet (1,400 m3) per second. After heavy rains combined with tides, it can even reach over 150,000 cubic feet (4,200 m3) per second.

Farther upriver, the flow rate is between 1,030 cubic feet (29 m3) per second near Lake Poinsett and 2,850 cubic feet (81 m3) per second near DeLand. Many springs, the Econlockhatchee River, and the Wekiva River all join the St. Johns. This causes the average flow to increase by 940 cubic feet (27 m3) per second between Lake Harney and DeLand. This is the biggest average yearly increase in flow along the St. Johns.

The farther you go from the ocean, the less salty the river water becomes. Ocean water is usually 35 parts per thousand (ppt) or more salty, while fresh water is below 2 ppt. Water in between is called "brackish." Near the center of Jacksonville, the average saltiness is about 11.40 ppt. Farther south at the Buckman Bridge, it drops to 2.9 ppt. At the Shands Bridge near Green Cove Springs, it falls even more to 0.81 ppt.

Dissolved oxygen in fresh water is important for the health of plants and animals. Oxygen gets into the water from the air and from aquatic plants making food (photosynthesis). Water pressure and temperature also affect it. If a lot of dead plants and animals break down quickly, the amount of dissolved oxygen in the river will go down. Also, nutrients from wastewater treatment runoff or fertilized farm fields can lower oxygen levels.

The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency and the State of Florida recommend at least 5 mg of oxygen per liter. In the 1990s and early 2000s, several places on the St. Johns or its smaller rivers had oxygen levels at or below this minimum. These included the mouth of the Wekiva River, the St. Johns near Christmas, Blue Spring, and Blackwater Creek. If oxygen levels stay low for too long, it can cause algal blooms, which can lower oxygen even more.

Like all blackwater streams in Florida, most of the St. Johns River is dark. This is because of tannins from decaying leaves and plants. However, streams fed by springs are very clear, and you can see the bottom even if the water is many feet deep.

Human History Along the St. Johns

Early People: Living by the River

Humans first arrived in Florida about 12,000 years ago. At that time, ocean levels were much lower, and Florida was twice its current size. These first people, called Paleo-Indians, were hunters and gatherers. They followed large animals like mastodons, horses, and bison. Much of the land was dry, with few trees, mostly grasslands.

Around 9,000 years ago, the climate got warmer. Ice caps melted, making the environment wetter and covering half of Florida's land. Since people didn't have to travel far for water, their camps became more permanent villages. Archeologists found many tools from this time, showing a shift to Archaic people. They made tools from bone, animal teeth, and antlers. They also wove fibers from plants.

Burial sites, like the Windover Archaeological Site near Titusville, show that Archaic people had burial rituals. They buried their dead in shallow peat marshes, which helped preserve human remains. Between 5,000 and 3,000 years ago, more climate changes led to the Middle Archaic period. Evidence suggests that people first lived near the St. Johns River during this time. The number of native people grew a lot, and many settlements from this era have been found near the St. Johns. The riverbanks are covered with middens (mounds of shells) filled with thousands of freshwater snails and oysters.

Around 500 BCE, people started making different types of pottery and stone tools from flint or limestone. The Archaic people became settled groups across Florida. From central Florida north along the Atlantic Coast, people lived in the St. Johns culture, named after the river. Around 750 CE, the St. Johns culture learned to grow corn. This added to their diet of fish, game, and gourds. Archeologists believe this farming led to a population increase.

When European explorers arrived in north Florida, they met the Timucua people, who numbered about 14,000. They were the largest native group in the area. Later, the Seminole people called the river Welaka or Ylacco. These names might come from a word meaning "big water" or "water coming," possibly because of the river's slow flow and tidal effects. The name is sometimes translated as "Chain of Lakes."

In 1955, a very rare Timucua totem shaped like an owl was found buried in the St. Johns muck near Hontoon Island. This figure might mean its creators were part of the owl clan. Two more totems, shaped like a pelican and an otter, were found in 1978. These are the only totems found in North America outside of the Pacific Northwest.

Colonial Era: European Settlers and Conflicts

The first European contact in Florida was in 1513 with Juan Ponce de León. But Europeans didn't settle the north Atlantic coast until 1562. Early Spanish explorers called the river Rio de Corientes (River of Currents). The St. Johns River became the first place colonized in the region and its first battleground.

In 1562, French explorer Jean Ribault put up a monument south of the river's mouth to show French presence. This worried the Spanish, who had been exploring the southern and western coasts for decades. In 1564, René Goulaine de Laudonnière arrived to build Fort Caroline at the mouth of the St. Johns River. They called the river Rivière de Mai because they settled it on May 1. An artist named Jacques LeMoyne drew what he saw of the Timucuan people in 1564. He showed them as strong and well-fed.

Fort Caroline didn't last long. Some French settlers left, and those who stayed were killed in 1565 by the Spanish, led by Pedro Menéndez. The Spanish marched north from St. Augustine and captured Fort Caroline. They renamed the river San Mateo. Capturing Fort Caroline helped the Spanish control the river.

The French and Spanish continued to fight over the land and native peoples. The Timucua, who had been friendly with the French, didn't become Spanish allies. By 1573, the Timucua were openly rebelling, forcing Spanish settlers to leave farms and forts. The Spanish couldn't stop the Timucua from attacking them.

Over a hundred years later, missionaries had more success, setting up posts along the river. Spanish Franciscan missionaries gave the river its current name, St. Johns, based on San Juan del Puerto (St. John of the Harbor). This was the name of the mission built at the river's mouth after the French fort was destroyed. The name first appeared on a Spanish map between 1680 and 1700.

The Timucua and other native groups in Florida began to decline by the 1700s. A tribe from Georgia and Alabama, called the Creeks, helped with this. In 1702, they attacked some Timucua, forcing them to seek protection from the Spanish, who then enslaved them. The Creeks started to include other people and spread south. By 1765, the British called them Seminoles, a term meaning "runaways" or "wild ones." The Seminoles spoke different languages from the people the Creeks had taken in. Between 1716 and 1767, the Seminoles slowly moved into Florida and became their own tribe. The St. Johns River became a natural border, separating European colonies on the east bank from native lands on the west.

After Florida became part of Great Britain in 1763, two naturalists, John and William Bartram, explored the river. They published journals describing their travels and the plants and animals they saw. King George III asked them to find the source of the river. They measured its width and depth and took soil samples.

William Bartram returned to Florida from 1773 to 1777 and wrote another journal. He collected plants and became friends with the Seminoles, who called him "Puc Puggy" (flower hunter). William traveled as far south as Blue Spring. He wrote about the clear spring water: "The water is perfectly clear, and here are continually a huge number and variety of fish; they appear as plain as though lying on a table before your eyes, although many feet deep in the water." Bartram's journals caught the attention of important Americans like James Madison and Alexander Hamilton. Other naturalists, like André Michaux, were inspired to explore the St. Johns. Michaux sailed from Palatka south to Lake Monroe in 1788 and named some of the plants Bartram described. Later explorers, including John James Audubon, used William's book Travels Through North & South Carolina, Georgia, East & West Florida as a guide.

In 1795, Florida was given back to Spain. Spain offered cheap land to Americans. Zephaniah Kingsley, a planter and slave trader, bought land near what is now Doctors Lake, close to the St. Johns River. He built a plantation called Laurel Grove. Three years later, Kingsley bought a 13-year-old girl named Anna Madgigine Jai from Cuba. She became his common-law wife and managed Laurel Grove while Kingsley traveled. The plantation grew citrus and sea island cotton. In 1814, they moved to a larger plantation on Fort George Island, where they lived for 25 years. Kingsley also owned other plantations and homes in what is now Jacksonville and on Drayton Island. Kingsley later married three other freed women. Spanish-controlled Florida allowed marriages between different races. Many white landowners along the river were married to or had relationships with African women.

Florida Becomes a State: Growth and Conflict

After Florida became part of the United States in 1821, there were violent conflicts between white settlers and Seminoles. Seminole groups often included runaway African slaves. The towns and landmarks along the St. Johns are named after people involved in these clashes.

Even before Florida was officially part of the U.S., Major General Andrew Jackson forced the Alachua Seminoles west of the Suwannee River in 1818. He either killed them or made them move south. Jackson's actions led to the First Seminole War. As a reward, a wide crossing of the St. Johns near the Georgia border, once called Cowford, was renamed Jacksonville.

After the Seminole Wars, trade and population slowly grew on the St. Johns. This was possible because of steamship travel. Steamboats were very popular and, before railroads, were the only way to reach inland parts of Florida. People in Jacksonville enjoyed watching steamboat races. By the 1860s, weekly trips between Jacksonville, Charleston, and Savannah carried tourists, lumber, cotton, and citrus. The soil along the St. Johns was known for growing very sweet oranges.

Florida's role in the U.S. Civil War was small compared to other Confederate states because it had fewer people. Florida sent supplies to the Confederacy using steamboats on the St. Johns. However, the U.S. Navy blockaded the river and the Atlantic coasts.

One event in Florida's Civil War history was the sinking of the USS Columbine. This was a Union paddle steamer used to patrol the St. Johns and stop supplies from reaching the Confederate Army. In 1864, near Palatka, Confederate forces led by Capt. John Jackson Dickison captured, burned, and sank the USS Columbine. This might make her the only Union ship captured by the Confederacy. In the same year, farther downriver, Confederates sank another Union boat, the Maple Leaf. It hit a floating barrel filled with explosives and sank into the muck near Julington Creek, south of Jacksonville. Part of the shipwreck was found in 1994. Many Civil War items, like old photographs and wooden matches, were preserved in the river muck.

Confederate Captain John William Pearson named his militia the Ocklawaha Rangers after the Ocklawaha River. Before the Civil War, Pearson ran a successful health resort in Orange Springs. After the war, his resort became less popular because of the growing interest in nearby Silver Springs in the early 1900s.

Poet Sidney Lanier called the Ocklawaha "the sweetest waterlane in the world" in a travel guide he published in 1876. The river gave Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings access to the St. Johns from her home at Orange Lake. The area was a major fishing spot until water quality declined in the 1940s. Since then, the river and its sources have become even more polluted. In particular, Lake Apopka became Florida's most polluted lake after a chemical spill in 1980. It has also had ongoing algal blooms from citrus farm fertilizer and wastewater runoff.

Even though Spain had colonized Florida for two centuries, it remained the last part of the U.S. east coast to be developed. After the Civil War, Florida was too much in debt to build roads and railroads. In 1881, Florida Governor William Bloxham asked Hamilton Disston, a businessman from Pennsylvania, for help. Disston was first asked to build canals to improve steamboat travel through the Caloosahatchee River. Later, he was asked to drain lands in central Florida for farming.

Disston was convinced to buy 4,000,000 acres (16,000 km2) of land in central Florida for $1 million. At the time, this was said to be the largest land purchase in human history. Disston's drainage efforts were not fully successful. However, his investment started the tourist industry and made it possible for railroad builders Henry Flagler and Henry Plant to build rail lines down Florida's east coast. This included a rail link between Sanford and Tampa. Disston was responsible for creating the towns of Kissimmee, St. Cloud, and others on Florida's west coast.

A New York Times story in 1883 reported on Disston's progress. It said that before Disston's purchase, the only places worth seeing in Florida were Jacksonville and St. Augustine, maybe with an overnight trip on the St. Johns River to Palatka. By 1883, tourist attractions had spread 250 miles (400 km) south. More attention was given to the St. Johns as the population grew. Florida was seen as an exciting place that could cure illnesses with its water and citrus. The region started to be featured in travel writings.

To help his bronchitis, Ralph Waldo Emerson stayed briefly in St. Augustine. He called north Florida "a strange region" that was being taken over by land speculators. Emerson also disliked the public sale of slaves. After the Civil War, famous author Harriet Beecher Stowe lived near Jacksonville and traveled up the St. Johns. She wrote about it with love: "The entrance of the St. Johns from the ocean is one of the most unique and impressive passages of scenery that we ever passed through: in fine weather the sight is magnificent." Her book Palmetto Leaves, published in 1873, was a collection of her letters home. It was very important in attracting people from the north to Florida.

One unexpected problem from more people coming to Florida was huge. Water hyacinths, possibly brought in 1884 by Mrs. W. W. Fuller, grew so thick that they became a serious invasive species. By the mid-1890s, these purple-flowered plants covered 50,000,000 acres (200,000 km2) of the river and its smaller waterways. The plants make it impossible for boats to pass, stop fishing, and block sunlight from reaching the river's depths. This harms both plant and animal life. The Florida government found the plants so annoying that it spent almost $600,000 between 1890 and 1930 trying to get rid of them, but it was unsuccessful.

Modern Era: Development and Restoration

An Englishman named Nelson Fell came to Florida in the 1880s, hoping to make a fortune. He was an engineer and bought 12,000 acres (49 km2) near Lake Tohopekaliga to create a town called Narcoossee. By 1888, it had over 200 English immigrants. After some bad luck, Fell invested in projects in Siberia. But he returned in 1909 with ideas to develop wetlands in central Florida. He was encouraged by Governor Napoleon Bonaparte Broward's promise to drain the Everglades during his 1904 campaign.

In 1910, Fell bought 118,000 acres (480 km2) of land for $1.35 an acre. In 1911, he started the Fellsmere Farms Company to drain the St. Johns Marsh and send water into the Indian River Lagoon. He promoted his canals as amazing ways to create land for a huge city. Some progress was made, including the town of Fellsmere, where land sold for $100 an acre. But sales slowed due to a scandal about land fraud and incorrect drainage reports from the Everglades. The company then ran out of money due to poor management. Heavy rains broke the new levees and dikes, forcing the company into financial trouble by 1916. Fell left Florida in 1917.

Marjorie Kinnan Rawlings used the St. Johns as a setting in her books South Moon Under and The Yearling, and in several short stories. In 1933, she took a boat trip on the St. Johns. In the upper basin, she noted how hard it was to tell which way the river was flowing. In her book Cross Creek, she wrote that watching the floating hyacinths was the best way to figure out the direction. Rawlings wrote, "If I could have, to hold forever, one brief place and time of beauty, I think I might choose the night on that high lonely bank above the St. Johns River."

In the 1900s, Florida saw a huge number of people move into the state. Undeveloped land sold quickly, and draining wetlands was often done without much control, even encouraged by the government. The St. Johns headwaters shrank from 30 square miles (78 km2) to one between 1900 and 1972. Much of the land was used for cities, but farming also caused problems. Fertilizers and runoff from cattle farms washed into the St. Johns. Without wetlands to filter these pollutants, the chemicals stayed in the river and flowed into the Atlantic Ocean. Boaters even used dynamite to destroy floating islands of muck and weeds in the upper basin, which caused lakes to drain completely.

One of the most serious human impacts on nature in central Florida could have been the Cross Florida Barge Canal. This project, first approved in 1933, aimed to connect Florida's Gulf and Atlantic coasts by channeling the Ocklawaha River. The canal was planned to be 171 miles (275 km) long, 250 feet (76 m) wide, and 30 feet (9.1 m) deep. Building the canal was a top engineering priority in Florida. By 1964, the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers began construction. Flood control was the main reason for its construction, but the overall purpose and whether it was truly needed were unclear.

The Army Corps of Engineers was also building hundreds of miles of canals in the Everglades at the same time. By the 1960s, they were accused of wasting tax money on unnecessary projects. In 1969, the Environmental Defense Fund sued in federal court to stop the canal. They argued it would cause permanent harm to Florida's waterways and the Floridan Aquifer, which is central and north Florida's fresh water source. The project was eventually stopped.

A separate canal, the St. Johns-Indian River Barge Canal, was planned to link the St. Johns River with the Intracoastal Waterway. This project never started and was canceled soon after the Cross Florida Barge Canal was stopped.

Restoration Efforts: Helping the River Heal

When railroads replaced steamboats, the river became less important to the state. Many new people moving to Florida settled south of Orlando, which negatively affected the wetlands there. However, in the last 50 years, cities in northern and central Florida have grown a lot. In the upper basin, the population grew by 700 percent between 1950 and 2000.

Nitrates and phosphorus from lawn and crop fertilizers wash into the St. Johns. Broken septic systems and runoff from cattle farms also pollute the river. Stormwater flows directly from street drains into the river and its smaller streams. In the 1970s, the Econlockhatchee River received 8,000,000 US gallons (30,000,000 L) of treated wastewater every day. Wetlands were drained and paved over, so they couldn't filter pollutants from the water. This problem was made worse by the river's slow flow.

Algal blooms, fish kills, and fish with deformities or sores happen regularly in the river from Palatka to Jacksonville. Even though most of the pollution comes from the southern parts of the river, the Jacksonville area produces about 36 percent of the pollutants found in the lower basin.

In 1987, the State of Florida started a program called Surface Water Improvement and Management (SWIM). This program helps clean up rivers, especially from nonpoint source pollution. This is pollution that enters the river by soaking into the ground, not from a direct pipe. SWIM helps local governments buy land to restore wetlands. The St. Johns River Water Management District (SJRWMD) is in charge of restoring the river.

The first step in restoration, especially in the upper basin, is buying public lands along the river. Ten different reserves and conservation areas have been created for this purpose around the St. Johns headwaters. Around Lake Griffin in the Ocklawaha Chain of Lakes, the SJRWMD bought 6,500 acres (26 km2) of land that was once used for farming. More than 19,000 acres (77 km2) have been bought along Lake Apopka to restore its wetlands. The SJRWMD has also removed nearly 15,000,000 pounds (6,800,000 kg) of gizzard shad (Dorosoma cepedianum), a fish that stores phosphorus and adds to algae problems. The SJRWMD also sets minimum water levels for the lakes and streams in the St. Johns area. This helps them monitor water use and declare water shortages when needed.

To help clean up the river and get funds for water quality improvements, Jacksonville Mayor John Delaney started a campaign in 1997. He wanted the St. Johns to be named an American Heritage River. This designation by the Environmental Protection Agency helps federal agencies work together to improve natural resources, protect the environment, boost the economy, and preserve history and culture.

The campaign was debated because the mayor was asking for federal help. He wrote, "Other rivers have relied heavily on federal help for massive environmental clean-ups. It's the St. Johns' turn now." Twenty-two towns along the St. Johns and many environmental, sporting, and educational groups supported the idea. However, some politicians worried about more federal rules and limits on private property along the river. The Florida House of Representatives even passed a resolution asking President Bill Clinton not to include the St. Johns. Despite this, Clinton named the St. Johns one of only 14 American Heritage Rivers in 1998. It was chosen for its important ecological, historic, economic, and cultural value.

The growing population in Florida has led urban planners to believe that the Floridan Aquifer won't be able to provide enough water for people in north Florida in the future. By 2020, it was predicted that 7 million people would live in the St. Johns basins, which is double the number from 2008. Proposals to use 155,000,000 US gallons (590,000,000 L) of water a day from the St. Johns, and another 100,000,000 US gallons (380,000,000 L) from the Ocklawaha River, for fresh water are controversial. This led a private group called St. Johns Riverkeeper to nominate it to the list of the Ten Most Endangered Rivers by American Rivers. In 2008, it was listed as #6. This was welcomed by Jacksonville's newspaper, The Florida Times-Union, but met with doubt from the SJRWMD.

The St. Johns River is still being considered as an extra water source for growing public needs. In 2008, the river's Water Management District started a study on how water withdrawals would affect the river. They asked the National Research Council to review the science behind the study. This led to four reports that looked at the impact of water withdrawal on river levels and flow, potential effects on wetland ecosystems, and overall thoughts on the District's study.

The National Research Council found that the District did a good job explaining the expected environmental changes from the proposed water withdrawals. However, the report noted that the District's final report should also consider important issues like future sea-level rises, population growth, and urban development. Even though the District predicted that changes in water management would increase water levels and flows, these predictions have high uncertainties.

The report also raised concerns about the District's idea that water withdrawals would have few harmful effects on the environment. This idea was based on models that showed increased flows from upper basin projects and from changes in land use (more paved areas) largely made up for the impacts of water withdrawals. While the upper basin projects are good because they return land to the basin (and water to the river), the same cannot be said for increased urban runoff, which is known to be of poor quality.

See also

In Spanish: Río St. Johns (Florida) para niños

In Spanish: Río St. Johns (Florida) para niños

- List of lakes of the St. Johns River

- List of crossings of the St. Johns River

- List of Florida rivers

- List of rivers of the Americas by coastline

- South Atlantic-Gulf Water Resource Region

| Jackie Robinson |

| Jack Johnson |

| Althea Gibson |

| Arthur Ashe |

| Muhammad Ali |