Golden Frinks facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Golden Asro Frinks

|

|

|---|---|

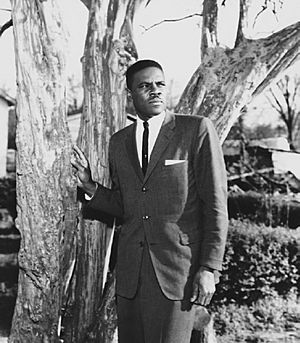

Golden Frinks as a field secretary of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, 1964

|

|

| Born | August 15, 1920 |

| Died | July 19, 2004 (aged 83) Edenton, North Carolina, US

|

| Organization | Southern Christian Leadership Conference |

| Spouse(s) | Mildred Ruth Holley |

| Children | Goldie Frinks Wells |

| Parent(s) |

|

Golden Asro Frinks (born August 15, 1920 – died July 19, 2004) was an American civil rights activist. He worked as a field secretary for the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). Frinks was a key leader in the civil rights movement in North Carolina during the 1960s.

He was also a veteran of the United States Army, fighting in World War II. After his military service, he started working to promote equality for African Americans. Frinks helped bring early civil rights victories to North Carolina. His use of nonviolent direct action helped start similar movements in Edenton and other towns.

As an SCLC field secretary, Frinks became close with Martin Luther King Jr.. He often worked with King to organize efforts to end segregation. Frinks' work helped begin a new era for civil rights in North Carolina. It also helped end segregation across the American South.

Contents

Golden Frinks' Early Life

Golden Asro Frinks was born on August 15, 1920. His parents, Mark and Kizzie Frinks, lived in Wampee, South Carolina. He was the tenth of eleven children in his family. His mother named him "Golden" after a special "golden text" she heard at church just before he was born.

When he was nine, Frinks moved to Tabor City, North Carolina. This small town was where he spent most of his childhood. His father worked as a millwright. His mother, Kizzie Frinks, worked as a helper for the town's mayor. After his father died, his mother raised the large family alone. She taught her children to fight for the changes they wanted to see. This lesson greatly influenced Frinks' desire to fight for racial equality.

Another important person in Frinks' childhood was Fannie Lewis. She was the wife of the town mayor. Mrs. Lewis had lost her own son and treated Frinks like her own. She helped him learn about the white community in Tabor City. This gave him ideas and knowledge that most black children did not get. At that time, Jim Crow laws were common in the South. These laws kept public places separate for black and white people. Frinks learned about these unfair laws from Mrs. Lewis. He also learned about black leaders who were fighting for change. This made him want to rebel against Jim Crow Laws from a young age.

Early Civil Rights Work and the Edenton Movement

At age sixteen, Frinks left Tabor City. He joined the United States Navy in Norfolk, Virginia. He later got a job at the U.S. naval base there. In Norfolk, he first learned about the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP). He learned about it from the active black community in the city.

In 1942, Frinks returned to Edenton. He married Mildred Ruth Holley, and they had a daughter named Goldie Frinks. Soon after, Frinks served briefly in the United States Army during World War II. After the war, he moved to Washington D.C. in 1948 to find new jobs. There, he had his first experience with civil rights protests.

In 1953, Frinks saw his boss at Waylie's Drug Store refuse to serve black teenagers lunch. This unfair act deeply bothered him. He then joined a six-month protest campaign at the drug store. Frinks led the protest daily, bringing others together to demand the store end segregation. His persistence showed him that protests could weaken Jim Crow Laws. The Supreme Court later ruled that segregated eating places in Washington, D.C., were illegal. This small victory showed Frinks the power of protest. It made him even more committed to fighting segregation.

Frinks soon left D.C. and returned to Edenton. He became active in the Chowan County Branch of the NAACP. He served as the chapter's secretary. During this time, Frinks noticed that some black leaders were afraid to protest. At a 1960 NAACP meeting, the local president refused to support black children's request to desegregate a theater. He feared losing his property.

The next day, Frinks resigned from the NAACP. He then organized his own protest with children from the NAACP Youth Council. He used what he learned from his D.C. protest. The theater protest was a success. This victory helped spread Frinks' name as a civil rights activist in North Carolina.

The local NAACP's hesitation pushed Frinks to take direct action. He started what became known as the Edenton Movement. This was a series of protests in the early 1960s to desegregate public places in Edenton. Frinks led young activists in town. Their efforts successfully ended segregation at places like the courthouse, library, and John A. Holmes High School.

The Edenton Movement brought national attention to the small town. But it also brought anger from the white community. Frinks faced threats and hate. Once, people burned a cross in his yard. They also left a dead rabbit with a message saying he would "end up like this rabbit" if he didn't stop protesting. Frinks later said he feared for his life and family. But he "kept praying and kept marching," showing his strong commitment.

Joining the Southern Christian Leadership Conference

In 1962, Frinks was arrested for the first time during the Edenton Movement. He was protesting at a theater and refused to stop. This was the first of his many arrests for civil rights protests. His direct methods often annoyed police, earning him the nickname "The Great Agitator."

During one protest in 1962, Frinks and several teenagers were arrested. The NAACP agreed to pay Frinks' bail but not the teenagers'. News of this reached Martin Luther King Jr., who was president of the Southern Christian Leadership Conference (SCLC). The SCLC is a major African-American civil rights group. It worked to end segregation in the South. King sent money to bail all the protesters out of jail. This is how Frinks' relationship with the SCLC began.

King and other SCLC leaders noticed Frinks' passion for civil rights. In 1963, the SCLC needed a field organizer in North Carolina. King asked Frinks to meet him in Norfolk. Frinks brought his pastor and a friend to speak for him. King then hired Frinks as one of the twelve national SCLC Field Secretaries. As a field secretary, Frinks oversaw efforts to end segregation in North Carolina. He also traveled to other states like Louisiana and Alabama to prepare for King's visits.

In his role, Frinks worked closely with King. He constantly organized civil rights activities. He also started campaigns in his hometown of Edenton and other rural areas of North Carolina.

The Williamston Freedom Movement

In the summer of 1963, King learned that garbage was not being collected in black communities in Williamston. This town was forty miles south of Edenton. King knew Frinks was familiar with eastern North Carolina. So, he sent Frinks to lead the black community in addressing this and other unfair issues. This effort became known as the Williamston Freedom Movement.

On June 30, 1963, Frinks and another activist, Sarah Small, led the first march on the Williamston town hall. This march lasted for twenty-nine days. Before the protest, Frinks met with other civil rights leaders. He passionately spoke about their plans to challenge Jim Crow Laws. One historian noted that Frinks' "streaks of wildness" helped him win civil rights victories. It also gained him support from other activists.

Frinks led several important protests in Williamston. On July 1, 1963, he led a protest to desegregate Watts Theater. This led to the first arrests of the movement. Other events included:

- A sit-in at Shamrock Restaurants.

- A march to protest segregation at S&V Food Store.

- A campaign to desegregate schools in Martin County. This also aimed to get equal resources for black students.

Frinks brought the black community together. A protester named Marie Robertson said, "The togetherness of the black people was something they were not accustomed to." Frinks' leadership helped unite people to fight inequality.

Information about Frinks' protests sometimes leaked to the white community. It even reached the local Ku Klux Klan. This was a big risk for Frinks. Some black people did not support Frinks' protests. This was often because they depended on white businesses for money. Many black people worked on tobacco farms for wealthy white owners. They feared losing their jobs if they protested. Frinks understood this problem. He used it to his advantage by leading boycotts of white businesses in Williamston. He encouraged black customers to shop elsewhere. This "power of the purse" helped weaken Jim Crow Laws. The boycotts hurt the local economy and gave the black community more power in talks about desegregation.

Death and Legacy

When Martin Luther King Jr. received the Nobel Peace Prize in 1964, he mentioned people like Frinks. He said, "I am always mindful of the many people who make a successful journey possible — the known pilots and the unknown ground crew." Frinks was not famous nationally, but he was vital to the civil rights movement. He played a big part in King's success.

In 1977, Frinks officially left his job with the SCLC. But he continued to support their work. In 1978, he said he was happy with his role in the fight for equality. He planned to continue his life's goal, even if he was no longer actively protesting. He stated, "If my people call, I will be ready to answer."

Frinks' dedication earned him many awards. These included:

- A resolution from the Georgia General Assembly.

- Recognition from the National SCLC.

- The Chowan County NAACP Achievement award.

- The Edenton Movement Service Award.

- The Rosa Parks Award.

- The North Carolina Black Leadership Caucus Award.

Golden Asro Frinks died on July 19, 2004, in Edenton, North Carolina. He was 84 years old. His lifelong commitment to civil rights inspired many others to fight for social justice and equality.

See also