Great Plague of Marseille facts for kids

The Great Plague of Marseille was the last big outbreak of bubonic plague in Western Europe. It arrived in Marseille, France, in 1720. This terrible disease killed over 100,000 people. About 50,000 died in Marseille over two years, and another 50,000 died in nearby towns and areas to the north.

Even though the city's economy recovered quickly, it took until 1765 for Marseille's population to return to what it was before 1720.

Contents

How Marseille Prepared for Plagues

The Health Board: Keeping the City Safe

After a plague in 1580, the city of Marseille decided to take action. They created a special group called the sanitation board, or health board. This board included city leaders and doctors. Their main job was to keep the city healthy and stop diseases from spreading.

The health board made many important rules. They built Marseille's first public hospital, which had many doctors and nurses. They also checked doctors to make sure they were trustworthy, especially during a plague when false information could spread easily.

Quarantine: Stopping Ships from Spreading Sickness

The health board set up a smart system to check incoming ships. They used a three-level quarantine system. When a ship arrived, board members would inspect it. They looked at the captain's logbook, which showed all the places the ship had visited. They compared this to a list of cities known to have the plague.

They also checked the ship's cargo, crew, and passengers for any signs of sickness. If they found any signs of disease, the ship was not allowed to dock in Marseille.

If a ship had no signs of sickness but had visited a plague-affected city, it went to the second level of quarantine. This happened at islands outside Marseille's harbor. These quarantine stations, called lazarets, were built to be airy and near the sea for cleaning. They were also isolated but easy to reach.

Even ships with a "clean bill of health" (meaning no signs of sickness) had to stay in quarantine for at least 18 days. The crew would stay in the largest lazaret, which had supplies. If crew members were thought to possibly have the plague, they went to a more isolated lazaret on an island. They had to wait there for 50 to 60 days to see if they got sick.

Once the quarantine time was over, the crew could enter the city to sell their goods and enjoy themselves before leaving.

The Plague Arrives and Spreads

The Great Plague of Marseille was the last major outbreak of bubonic plague in Europe after the terrible Black Death that started in the 1300s. In May 1720, the plague arrived in Marseille. It came on a merchant ship called the Grand-Saint-Antoine from the Middle East. The ship had visited places where the plague was active.

A passenger on the ship got sick and died first, then several crew members and the ship's doctor. The ship was not allowed to dock in another port before it reached Marseille.

When the ship arrived in Marseille, it was put under quarantine at the lazaret. However, powerful merchants in the city wanted the ship's valuable cargo, like silk and cotton, for a big market. They pressured the authorities to let the ship's goods into the city, even though it was still under quarantine.

A City Overwhelmed

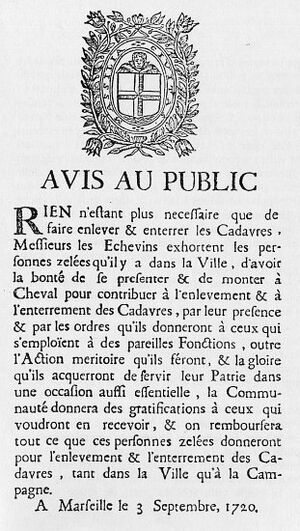

Just a few days later, the disease broke out in the city. Hospitals quickly became full, and people panicked. They even forced sick people out of their homes. Mass graves were dug, but they filled up very quickly. Soon, there were so many dead bodies that they lay scattered in piles around the city.

To try and stop the plague from spreading, the government made a strict rule: anyone traveling between Marseille and the rest of Provence could face the death penalty. To enforce this, a "plague wall," or mur de la peste, was built across the countryside. This wall was made of dry stone, about 2 meters (6.5 feet) high and 70 centimeters (2.3 feet) thick, with guard posts. Parts of this wall can still be seen today.

Chevalier Roze: A Hero of the Plague

A man named Nicolas Roze, who had experience dealing with epidemics, offered to help the city leaders. Because of his experience, he was made a special commissioner for a part of the city. He set up checkpoints to create a quarantine and even built gallows to scare away looters.

Roze also organized the digging of five large mass graves. He turned a rope-making factory into a field hospital and arranged for food and supplies to be given to the people.

On September 16, 1720, Roze personally led a group of 150 volunteers and prisoners to remove 1,200 dead bodies from a poor neighborhood. Some of these bodies were three weeks old and in terrible condition. In just half an hour, the bodies were thrown into open pits, covered with lime, and then with soil.

Out of 1,200 people who helped fight the plague, only three survived. Roze himself caught the disease but recovered, which was very lucky since most people didn't survive without modern medicine.

The Terrible Toll

Over two years, 50,000 of Marseille's 90,000 residents died. Another 50,000 people died as the plague spread north to other towns like Aix-en-Provence, Arles, Apt, and Toulon. In some areas, more than half the population died.

After the plague ended, the government made the port's defenses even stronger. They built a new quarantine station called the Lazaret d'Arenc with high walls. Ships had to be inspected at an island further out in the harbor before they could unload their goods.

Learning from the Past

In 1998, scientists from the Université de la Méditerranée dug up a mass grave of plague victims. They studied over 200 skeletons from a monastery in Marseille. By combining modern lab tests with old records, they learned new things about the 1722 epidemic. For example, they found the first historical evidence of an autopsy (a medical examination of a body after death) from that time on a 15-year-old boy. The methods used were similar to those described in a surgery book from 1708.

See also

- List of Bubonic plague outbreaks

- Plague of Justinian

- Popular revolt in late medieval Europe

- Moscow plague riot of 1771

- Second plague pandemic

- Third plague pandemic

- Nicolas Roze (chevalier)

- COVID-19 in France

| George Robert Carruthers |

| Patricia Bath |

| Jan Ernst Matzeliger |

| Alexander Miles |