Grigori Perelman facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Grigori Perelman

|

|

|---|---|

| Григорий Перельман | |

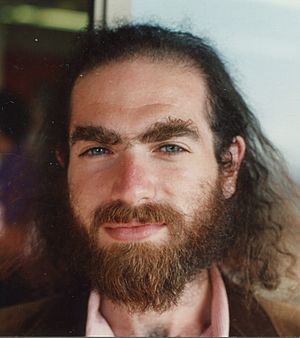

Perelman in 1993

|

|

| Born |

Grigori Yakovlevich Perelman

13 June 1966 |

| Education | Leningrad State University (PhD) |

| Known for | Proof of the soul conjecture, Poincaré conjecture and geometrization of 3-manifolds |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields |

|

| Institutions |

|

| Thesis | Saddle Surfaces in Euclidean Spaces (1990) |

| Doctoral advisor |

|

Grigori Yakovlevich Perelman (born June 13, 1966) is a Russian mathematician. He is famous for his important work in areas of math like geometric analysis and geometric topology. These fields study the shapes and sizes of objects, often in very complex ways.

In 2005, Perelman left his job at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics. In 2006, he said he had stopped working as a professional mathematician. He felt disappointed with how people acted in the math world. He now lives a quiet life in Saint Petersburg, Russia. He has not given any interviews since 2006.

In the 1990s, Perelman worked on a math idea called Alexandrov spaces. In 1994, he solved the soul conjecture, a math problem that had been unsolved for 20 years. Later, in 2002 and 2003, he developed new ways to understand something called Ricci flow. Using these new ideas, he proved the Poincaré conjecture and Thurston's geometrization conjecture. The Poincaré conjecture was a very famous unsolved math problem for over 100 years.

In August 2006, Perelman was offered the Fields Medal. This is one of the highest awards a mathematician can receive. He was offered it for his "revolutionary insights" into Ricci flow. However, he turned down the award. He said, "I'm not interested in money or fame; I don't want to be on display like an animal in a zoo." In December 2006, the science magazine Science called his proof of the Poincaré conjecture the scientific "Breakthrough of the Year." This was the first time a math discovery received this honor.

On March 18, 2010, it was announced that he had met the requirements for the first Millennium Prize. This prize came with one million dollars for solving the Poincaré conjecture. But on July 1, 2010, he also refused this prize. He felt that the decision by the Clay Institute was unfair. He believed his work was no more important than that of Richard S. Hamilton. Hamilton was another mathematician who helped develop the Ricci flow method. Perelman had also turned down a big prize from the European Mathematical Society in 1996.

Contents

Early Life and Schooling

Grigori Yakovlevich Perelman was born in Leningrad, Soviet Union (now Saint Petersburg, Russia) on June 13, 1966. His parents were Jewish. His mother, Lyubov, gave up her own math studies to raise him.

Perelman's math talent showed up when he was only 10 years old. His mother enrolled him in a special after-school math program. He then went to the Leningrad Secondary School 239. This was a special school with advanced math and physics classes. Perelman was excellent in all subjects except physical education.

In 1982, just after his 16th birthday, he won a gold medal. He was part of the Soviet team at the International Mathematical Olympiad in Budapest. He got a perfect score in the competition. He then went to Leningrad State University to study math. He didn't even need to take admission exams because he was so good.

After getting his PhD (a high-level university degree) in 1990, Perelman started working at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics. In the early 1990s, he got research jobs at several universities in the United States. In 1991, he won a prize for young mathematicians. In 1993, he accepted a special two-year research position at the University of California, Berkeley. After solving the soul conjecture in 1994, many top universities offered him jobs. But he turned them all down. He returned to the Steklov Institute in Saint Petersburg in 1995 for a research-only job.

Solving the Poincaré and Geometrization Problems

The Big Math Problems

The Poincaré conjecture was a very famous math problem. It was first suggested by mathematician Henri Poincaré in 1904. For nearly 100 years, it was one of the biggest unsolved problems in topology. Topology is a branch of math that studies shapes and spaces.

Imagine a 3-sphere. This is like the surface of a ball, but in four dimensions. On this 3-sphere, any loop you draw can be shrunk down to a single point. Poincaré wondered if the opposite was true. If a three-dimensional space has the property that any loop can be shrunk to a point, does it have to be like a 3-sphere? This was a very hard question to answer.

In 1982, William Thurston came up with a new idea. He thought the Poincaré conjecture was just a small part of a bigger theory. This theory was about how all three-dimensional spaces could be understood. His idea was called the Thurston geometrization conjecture. It suggested that any three-dimensional space could be cut into pieces. Each piece would then have a special, uniform geometric shape.

Around the same time, Richard Hamilton introduced his idea of the Ricci flow. This is a mathematical process that changes the shape of a space over time. It's a bit like how heat spreads out until everything is the same temperature. Hamilton showed that Ricci flow could make shapes more uniform. But sometimes, "singularities" would appear. These are points where the shape becomes infinitely curved. Hamilton thought that understanding these singularities could help solve Thurston's conjecture.

Perelman's Breakthrough Work

In 2002 and 2003, Perelman posted three papers online. In these papers, he explained his proof of Thurston's conjecture. His work was based on Hamilton's Ricci flow theory.

Perelman's first paper introduced two main ideas. One was the "noncollapsing theorem." This showed that if you control how curved a space is, you can also control its size. This was very important for using Hamilton's methods. The second big idea was the "canonical neighborhoods theorem." This helped understand how the "singularities" (the infinitely curved points) appeared in three-dimensional Ricci flow. Perelman showed that these singularities look like either a cylinder or a sphere collapsing.

In his second paper, Perelman used his new ideas to create a "Ricci flow with surgery." This method allowed him to cut out the singular parts of the space as they formed. By doing this, he could show that the Ricci flow could continue without problems. This "Ricci flow with surgery" was the key to proving the Poincaré conjecture.

To prove the full Thurston conjecture, Perelman had to analyze Ricci flows that could go on forever. He adapted Hamilton's arguments to fit his new Ricci flow with surgery. His work was a huge step forward in mathematics.

Checking the Proofs

Perelman's papers quickly got a lot of attention from mathematicians. But they were hard to understand because they were very short and didn't explain every detail. It took time for the math community to fully check his work.

In April 2003, Perelman visited several universities in the United States. He gave talks to explain his work to other experts. Over the next few years, three detailed explanations of his proof were published by other mathematicians:

- Bruce Kleiner and John Lott published notes that filled in the missing details from Perelman's papers. They said that while Perelman's proofs were "concise and, at times, sketchy," they "did not find any serious problems."

- Huai-Dong Cao and Zhu Xiping also published a complete description of the proof. They said that the work was a team effort, but Hamilton and Perelman were the main contributors.

- John Morgan and Gang Tian published a detailed presentation of Perelman's proof. In 2006, Morgan announced that Perelman's work had been "thoroughly checked."

These detailed explanations confirmed that Perelman's proof was correct.

Fields Medal and Millennium Prize

In May 2006, a group of top mathematicians decided to give Perelman the Fields Medal. This medal is like the Nobel Prize for mathematics. But Perelman refused to accept it. Sir John Ball, the head of the International Mathematical Union, even went to Saint Petersburg to try and convince him. After 10 hours of talking, Ball gave up.

Perelman explained his decision: "I'm not interested in money or fame, I don't want to be on display like an animal in a zoo. I'm not a hero of mathematics. I'm not even that successful; that is why I don't want to have everybody looking at me." He also said, "Everybody understood that if the proof is correct, then no other recognition is needed."

On August 22, 2006, at a big math conference in Madrid, Perelman was officially offered the Fields Medal. He was not there, and the presenter announced that he had declined it. This made him the only person ever to refuse the Fields Medal. He had also turned down a major prize from the European Mathematical Society in 1996.

On March 18, 2010, Perelman was awarded a Millennium Prize for solving the Poincaré conjecture. This prize came with one million dollars. But on June 8, 2010, he did not go to the ceremony to accept the money. In July 2010, he officially refused the prize. He felt that the Clay Institute's decision was unfair because they didn't share the prize with Richard S. Hamilton. Perelman said, "the main reason is my disagreement with the organized mathematical community. I don't like their decisions, I consider them unjust."

The Clay Institute later used Perelman's prize money to create a special position for young mathematicians in Paris.

Life After Mathematics

Perelman left his job at the Steklov Institute of Mathematics in December 2005. His friends have said that he finds math a difficult topic to talk about now. By 2010, some even thought he had completely stopped doing mathematics.

In a 2006 article, Perelman said he was disappointed with the ethical standards in the field of mathematics. He felt that some mathematicians were not honest and that others tolerated this behavior. He said, "It is not people who break ethical standards who are regarded as aliens. It is people like me who are isolated."

This feeling, along with the possibility of getting the Fields Medal, led him to say he had quit professional mathematics by 2006. He explained, "As long as I was not conspicuous, I had a choice. Either to make some ugly thing or, if I didn't do this kind of thing, to be treated as a pet. Now, when I become a very conspicuous person, I cannot stay a pet and say nothing. That is why I had to quit."

It's not clear if he completely stopped his math research after leaving his job. Another Russian mathematician, Yakov Eliashberg, said that Perelman told him in 2007 he was working on other things. Perelman has also shown interest in the Navier–Stokes equations, which are important in physics.

In 2014, some news reports said Perelman was working in nanotechnology in Sweden. However, he was later seen back in his hometown of Saint Petersburg. It is thought that he might visit his sister in Sweden sometimes, but he mostly lives in Saint Petersburg and takes care of his elderly mother.

Perelman and the Media

Perelman has always avoided journalists and the media. Masha Gessen, who wrote a book about him, could not meet him. When one reporter called him, he said, "You are disturbing me. I am picking mushrooms."

In 2011, a Russian documentary about Perelman was released. It was called "Maverick: Perelman's Lesson." In this film, several leading mathematicians discuss his work.

In April 2011, a film producer claimed to have interviewed Perelman. He said Perelman explained why he refused the million-dollar prize. However, many journalists believe this interview was likely fake. They pointed out things Perelman supposedly said that didn't make sense.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Grigori Perelmán para niños

In Spanish: Grigori Perelmán para niños

- 50033 Perelman

- Poincaré conjecture

- Thurston geometrization conjecture

| Frances Mary Albrier |

| Whitney Young |

| Muhammad Ali |