Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer

|

|

|---|---|

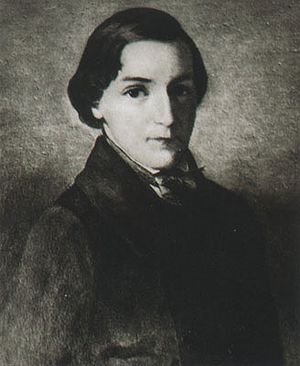

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer by his brother, Valeriano Bécquer

|

|

| Born | Gustavo Adolfo Domínguez Bastida 17 February 1836 Seville, Spain |

| Died | 22 December 1870 (aged 34) Madrid, Spain |

| Occupation | Poet, writer, journalist |

| Nationality | Spanish |

| Signature | |

Gustavo Adolfo Claudio Domínguez Bastida (born February 17, 1836 – died December 22, 1870), known as Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer, was a famous Spanish Romantic poet and writer. He mostly wrote short stories. He was also a playwright, a journalist, and a talented artist.

Today, he is seen as one of the most important people in Spanish literature. Some even say he is the most read Spanish writer after Miguel de Cervantes. He used the name Bécquer because his brother Valeriano Bécquer, who was a painter, used it too. Gustavo Bécquer was part of the romanticism movement. He wrote when realism was popular in Spain.

He was somewhat known during his life. But most of his works were published after he died. His most famous works are the Rhymes (Rimas) and the Legends (Leyendas). These are usually published together. These poems and tales are very important for studying Spanish literature. High school students in Spanish-speaking countries often read them.

Bécquer's work brought a modern touch to old poetry and themes. He is seen as the founder of modern Spanish lyricism (poetry that expresses feelings). His writing influenced many 20th-century Spanish poets. These include Luis Cernuda, Octavio Paz, Antonio Machado, and Juan Ramón Jiménez. Bécquer himself was inspired by writers like Cervantes, Shakespeare, Goethe, and Heinrich Heine.

Contents

Biography

Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer was born in 1836. His original last name was Domínguez Bastida. But he chose his father's second last name, Bécquer. This name came from his Flemish family. His father, José Domínguez Bécquer, was a well-known painter in Seville. The Bécquer family had lived in Seville since the 16th century.

José's paintings were popular, especially with tourists. His great talent influenced young Gustavo. Gustavo loved painting and drawing from a young age. He was very skilled and kept drawing throughout his life. However, art was never his main focus.

Bécquer became an orphan early in life. He lost his father when he was 5. His mother died just 6 years later. Young Gustavo started school at San Antonio Abad. In 1846, he joined San Telmo school, which was a nautical school. There, he met Narciso Campillo. They became strong friends. Bécquer and Campillo began writing together at San Telmo. This showed Gustavo's love for literature.

A year later, the school closed. Gustavo and his siblings went to live with their uncle, Don Juan de Vargas. He cared for them like his own children. Soon after, Gustavo moved in with his godmother, Doña Manuela Monahay. She had a huge library. Young Bécquer spent many hours enjoying her books. Doña Manuela was happy to let him read. Campillo remembered that Gustavo rarely left his godmother's house. He spent hours reading her many books.

Gustavo's godmother was well-educated and wealthy. She supported his interest in arts and history. But she wanted Gustavo to have a job. So, in 1850, she helped him join the studio of Don Antonio Cabral Bejarano. This was at the Santa Isabel de Hungría school. Gustavo worked there for only two years. Then he moved to his uncle Joaquin's studio. He continued to improve his art skills there. His brother Valeriano was already studying there. Gustavo and Valeriano became very close friends. They influenced each other a lot throughout their lives. Their brother Luciano also studied with them.

Studying drawing did not stop Gustavo's love for poetry. Also, his uncle Joaquin paid for his Latin classes. This helped him read his favorite poet, Horace. Horace was one of his first inspirations. Joaquin also saw that Gustavo was very good with words. He encouraged him to become a writer. This was different from what Doña Manuela wanted. Gustavo was still living with her at the time.

In 1853, when he was seventeen, he moved to Madrid. He wanted to become a famous poet. He and his friends, Narciso Campillo and Julio Nombela, had dreamed of moving to Madrid. They hoped to sell their poetry for good money. But reality was very different. Nombela was the first to go to Madrid that year with his family. After many arguments with Doña Manuela, Bécquer finally left for Madrid in October. He went alone and was quite poor. He only had a little money from his uncle. Campillo, the third friend, did not leave Seville until later.

Life in Madrid was hard for the poet. The dream of becoming rich was replaced by tough times and disappointments. Soon, Luis García Luna, another poet from Seville, joined the two friends. He had the same dreams of greatness. The three began writing and trying to become known authors. But they did not have much luck. Bécquer was the only one without a steady job. He went to live with an acquaintance of Luna, Doña Soledad. A year later, in 1854, he moved to Toledo with his brother Valeriano. Toledo was a beautiful place. There, he wrote his book: "History of the Spanish temples." The poet was interested in Lord Byron's "Hebrew Melodies" and Heine's "Intermezzo." Eulogio Florentino helped him with the translations.

The poet died on December 22, 1870. He died from tuberculosis. This illness was known as "the romantic illness." It was common during the Romantic period in Spain. Before he died, Bécquer asked his friend, Augusto Ferrán, to burn all his letters. Instead, he wanted his poems published. He believed his work would be more valuable after his death. His body was buried in Madrid. Later, it was moved to Seville, along with his brother's body.

Early career

Bécquer tried to start businesses with his friends, but they failed. Finally, he got a job as a writer for a small newspaper. But this job did not last long. Soon, Gustavo was jobless again. In 1855, Valeriano came to Madrid. Gustavo went to live with his brother. They stayed together from then on.

After more failed attempts to publish their work, Bécquer and Luna started writing funny plays for theater. This was how they made a living. They worked together until 1860. During this time, Bécquer worked hard on his project Historia de los templos de España (History of Spain's temples). The first part of this book came out in 1857. Also, during this period, he met the young Cuban poet Rodríguez Correa. Correa would later help a lot in collecting Bécquer's works after his death.

Around 1857 and 1858, Bécquer became ill. His brother and friends took care of him. Soon after, he met a girl named Julia Espín. He fell deeply in love with her. She inspired many of his romantic poems. However, his love for her was not returned.

Around 1860, Rodríguez Correa helped Bécquer get a government job. But Bécquer was soon fired. He spent his time writing and drawing instead of working.

Love life and literary career

In 1861, Bécquer met Casta Esteban Navarro. They married in May 1861. Before his marriage, Bécquer was thought to have been with another girl named Elisa Guillén. Some believe his marriage to Casta was arranged or somewhat forced by her parents. The poet was not happy in his marriage. He took every chance to travel with his brother Valeriano. Bécquer wrote very little about Casta. Most of his inspiration, like for the famous rima LIII, came from his feelings for Elisa Guillén. Casta and Gustavo had three children: Gregorio Gustavo Adolfo, Jorge, and Emilio Eusebio.

In 1865, Bécquer stopped writing for the newspaper El Contemporáneo. He had become famous there. He started writing for two other newspapers, El Museo Universal and Los Tiempos. The latter was started after El Contemporáneo closed. He also got a government job called fiscal de novelas. This meant he supervised novels and published literature. His friend and supporter, Luis González Bravo, gave him this job. González Bravo was a former President of Spain and the Spanish Minister of Home Affairs.

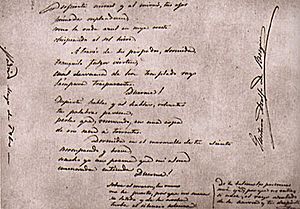

This was a good-paying job. Bécquer held it on and off until 1868. Through this job, he helped his brother Valeriano get a government payment. Valeriano received it for painting "Spanish regional folk costumes and traditions." During this time, the poet focused on finishing his poem collections. These were Rimas (Rhymes) and Libro de los gorriones (Book of the Sparrows). So, he did not publish many of his works.

A finished copy of his poems was given to Luis González Bravo for publishing. González Bravo was President of Spain again in 1868. But sadly, the manuscript was lost during the political revolution of 1868. This revolution forced President Luis González Bravo and Queen Isabella II of Spain to leave Spain for France. At this time, the poet also left Spain for Paris. But he returned not long after. By 1869, the poet and his brother went back to Madrid with Gustavo's sons. Here, he started rewriting the book that had gone missing.

Gustavo was living a free-spirited life, as his friends later said. To earn money, Bécquer went back to writing for El museo universal. Then he became the literary director of a new art magazine called La ilustración de Madrid. Valeriano also worked on this project. Gustavo's writings in this magazine were mostly short texts. They went along with his brother's drawings.

In 1870, Valeriano became ill and died on September 23. This greatly affected Gustavo. He became very sad. After publishing a few short works in the magazine, the poet also became very ill. He died in poverty in Madrid on December 22. This was almost three months after his beloved brother. The exact cause of his death is debated. His friends said he had symptoms of lung tuberculosis. But a later study suggests he might have died from liver problems. Some of his last words are said to be "Remember my children."

After his death, his friend Rodríguez Correa worked with Campillo, Nombela, and Augusto Ferrán. They collected and organized his writings to publish them. This was a way to help the poet's wife and children. The first edition of their work came out in 1871. A second book was published six years later. More updated versions were released in 1881, 1885, and 1898.

Bécquer's prose tales like El Rayo de Luna, El Beso, and La Rosa de Pasión show the influence of E.T.A. Hoffmann. As a poet, he is similar to Heine. His work is not always finished or perfect. But it is very honest and sweet. It does not have the flowery language common in his home region of Andalusia. He also wrote letters, like Cartas desde mi Celda, written during his trips to Veruela's Monastery. He also wrote La Mujer de Piedra and short plays like La novia y el pantalón. Many people do not know that he was an excellent artist. Most of his work focused on the natural feeling of love and the quietness of nature. His work, especially his Rimas, is considered some of the most important in Spanish poetry. It greatly influenced later writers. These include Antonio Machado and Juan Ramón Jiménez. It also influenced writers from the Generation of '27, like Federico García Lorca and Jorge Guillén. Many Latin American writers, like Rubén Darío, were also influenced.

Works

Rhymes (Rimas)

Bécquer's poems were memorized by people of his time. They greatly influenced later generations. Bécquer's 77 Rimas were written in short stanza forms. They total a few thousand lines. They are seen as the start of modern Spanish poetry. Luis Cernuda wrote: 'Bécquer has a key quality as a poet: he expresses things with a clarity and strength that only classic writers have... Bécquer plays a role in our modern poetry similar to Garcilaso's in our classic poetry: he created a new tradition that he passed on to others.' His book was put together after his death from many sources. The main source was a manuscript by Bécquer himself, called The Book of Sparrows.

Birds often appear in Bécquer's writings. For example, in "Rima LIII" (Rhyme 53), swallows show the end of a passionate relationship.

|

Volverán las oscuras golondrinas |

The dark swallows will return |

The line "¡Esas... no volverán!" appears in the 20th-century novel Yo-Yo Boing! by Puerto Rican poet Giannina Braschi. She uses Bécquer's swallows to describe the sadness of a broken romance.

In Rhymes (Rhyme 21), Bécquer wrote one of the most famous poems in Spanish. The poem can be seen as an answer to a lover who asked what poetry was:

|

¿Qué es poesía?, dices mientras clavas |

What is poetry? you ask, while fixing |

Legends

The Legends are a collection of romantic tales. As the name suggests, most of them have a legendary feel. Some describe supernatural and religious events. Examples include The Mount of the Souls, The Green Eyes, The Rose of the Passion (which mentions the Holy Child of la Guardia), and The miserere (a religious song). Other legends cover more normal events from a romantic point of view. These include The Moonlight Ray and Three Dates.

The Leyendas (Legends) are:

- El caudillo de las manos rojas, 1858.

- La vuelta del combate, 1858. (Continued: El caudillo de las manos rojas).

- La cruz del diablo, 1860.

- La ajorca de oro, 1861.

- El monte de las ánimas, 1861.

- Los ojos verdes, 1861.

- Maese Pérez, el organista, 1861.

- Creed en Dios, 1862.

- El rayo de luna, 1862.

- El Miserere, 1862.

- Tres fechas, 1862.

- El Cristo de la calavera, 1862.

- El gnomo, 1863.

- La cueva de la mora, 1863.

- La promesa, 1863.

- La corza blanca, 1863.

- El beso, 1863.

- La Rosa de Pasión, 1864.

- La creación, 1861.

- ¡Es raro!, 1861.

- El aderezo de las esmeraldas, 1862.

- La venta de los gatos, 1862.

- Apólogo, 1863.

- Un boceto del natural, 1863.

- Un lance pesado.

- Memorias de un pavo, 1865.

- Las hojas secas.

- Historia de una mariposa y una araña.

- La voz del silencio, 1923, Released by Fernando Iglesias Figueroa.

- La fe salva, 1923, Released by Fernando Iglesias Figueroa.

- La mujer de piedra, Unfinished.

- Amores prohibidos.

- El rey Alberto.

Narrative

He also wrote some prose stories called "Narraciones." These stories are full of imagination and unlikely events. One example is "Memorias de un Pavo" (Memoirs of a Turkey). In this story, a turkey describes its journey from a farm to the city. It tells how it was bought to be eaten. Its writings are found inside its cooked body.

Images for kids

See also

In Spanish: Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer para niños

In Spanish: Gustavo Adolfo Bécquer para niños