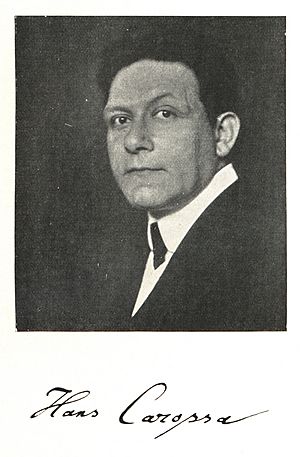

Hans Carossa facts for kids

Hans Carossa (born December 15, 1878, died September 12, 1956) was a German writer and poet. He is best known for his books that tell stories from his own life. During the time of Nazi Germany, he practiced "inner emigration", which meant he stayed in Germany but quietly disagreed with the government.

He studied medicine and worked as a doctor in the army from 1916 to 1918. He received important awards for his writing, like the Swiss Gottfried Keller Prize in 1931 and the Goethe Prize in 1938.

Contents

Hans Carossa's Life Story

His Family and Early Years

Hans Carossa's family originally came from northern Italy, but by the time he was born in 1878, they were considered German. His father was a well-known doctor who specialized in lung problems. He was a calm and kind person. Hans's mother was very religious and sensitive.

Hans was born in Bad Tölz, a town in southern Bavaria. His family moved several times, which made young Hans feel a bit unsure. He went to different schools and started to love poetry at a young age. However, his family also had a tradition of medicine. This made him wonder if he should be a poet or a doctor.

He studied medicine at three different universities: Munich, Würzburg, and Leipzig. But he spent most of his free time with other writers. Around 1900, when he was 24, Carossa started working as a doctor in Passau. In 1907, he married Valerie Endlicher and moved to the countryside.

Starting His Writing Career

Hans Carossa's first poem, Stella Mystica, was published in 1907. This poem showed a theme he would often write about: believing that good will always win over bad. It wasn't as polished as his later work, but it showed his promise.

In 1908, Carossa almost stopped being a doctor to focus on writing. His first collection of poems, called Gedichte, came out three years later. This also started his long relationship with the Insel publishing company.

Being a doctor, especially dealing with very sick patients, was hard for him. He tried to write about these difficult feelings, just like his favorite writer Goethe did. Carossa's book Doktor Bürgers Ende (1913) was similar to Goethe's work. It helped Carossa find his own writing style. He wrote about his feelings for his patients: "The lost ones are closest to my heart now, those I know I will not save."

Before World War I, Carossa was very interested in literature. He took notes, planned books, and looked for advice from other writers like Rilke and Hofmannsthal.

World War I Experiences

In 1914, Carossa volunteered to be an army doctor, even though he was a bit old for it. During his time in the military, he wrote down his childhood memories, which later became the book Eine Kindheit. He also kept a diary of his war experiences, published as Rumänisches Tagebuch. These notes also helped him write Führung und Geleit.

Carossa served as a doctor on both the French and Romanian fronts. He was involved in the Second Battle of Oituz in Romania. In 1918, he was wounded in the shoulder in France, which ended his time in the army.

Life After the War

After the war, Munich, which Carossa remembered as a lively city, was sad and quiet. He felt he wasn't a great poet yet, and his main path was still to be a doctor.

He met the poet Rilke while buying new medical tools, and Rilke became his first patient when he started practicing medicine again in Passau. Carossa worked hard to improve his medical skills. He later moved to Munich, hoping to become a full-time writer, but it wasn't possible yet.

Still, Carossa found time for writing. In 1922, he published the first part of his autobiography, Eine Kindheit. This book was very successful and made him excited about writing again. His income from writing slowly grew, making him less dependent on his medical practice. In 1923, he published a larger version of his Gedichte and his war diary, Rumänisches Tagebuch. This book was very popular and helped him financially.

His success allowed him to visit Italy in 1925, a trip that was very important to Goethe. However, the world was changing. Italy had become a Fascist country, and Germany was seeing the rise of the National Socialist German Workers' Party. Carossa didn't seem too worried by these political changes. When he returned from Italy, he mostly focused on writing, only treating old friends as patients. Soon after, he published the second part of his autobiography, Verwandlung einer Jugend (1926). That same year, his friend Rilke passed away.

Not much is known about Carossa's life between the mid-1920s and early 1930s. He was concerned about his wife's illness and started a relationship with Hedwig Kerber, with whom he had a child in 1930. The difficult German economy might have made him return to his medical practice more. He did rewrite Doktor Bürger in 1929 and was honored by Munich with a poetry prize.

In 1931, Carossa published Der Arzt Gion. This was his first major book written about a character in the third person, not himself. It showed a hopeful and mature outlook, which was unusual for Europe at that time, as it faced economic problems and the rise of dictators. After this, Carossa mostly stopped practicing medicine to focus entirely on writing. His last book before the Nazi regime began was Führung und Geleit (1932), which looked back at his life.

During Nazi Germany

After the Nazis took power in 1933, Carossa chose "Inner emigration". This meant he stayed in Germany but didn't support the Nazi government. He refused to join the German Academy of Poetry. However, in 1938, he accepted the Goethe Prize. In 1941, he became the president of the European Writers' League, which was started by Joseph Goebbels, a high-ranking Nazi official.

Carossa even contributed a poem to a book called "To the Leader. Words by German poets". In this poem, he wrote:

- " ... Encouraged we return to our own task

- and wish to the brave one,

- to the fighter and leader who bears all our destiny

- the best and good luck."

The next year, he avoided similar events. Even though he kept a distance from the Nazi regime, Carossa was one of the most promoted writers. In 1944, during the final part of World War II, Adolf Hitler included Carossa on a special list of the six most important German writers.

Carossa received awards and honors from neutral and friendly countries, and his income grew a lot. He used his position to help others. For example, in 1941, he helped the writer Alfred Mombert, who was in danger because he was Jewish, to leave Germany for Switzerland.

Just before Germany surrendered in 1945, Carossa wrote a letter to the mayor of Passau, asking him to surrender the city without a fight. Because of this, he was sentenced to death in his absence. However, the quick arrival of the US Army saved him.

After 1945

After the war, Carossa thought about his role during the Nazi era. His book Ungleiche Welten (Unequal Worlds) from 1951 was criticized because some felt it made his actions seem less serious and presented him as someone who couldn't resist the Nazis.

In West Germany, he became popular again, just like he was in the 1920s and 1930s. The German President, Theodor Heuss, even visited him at his home in 1954.

Many places are named after Hans Carossa today. These include the Hans-Carossa-Gymnasium schools in Landshut and Berlin, elementary schools in Pilsting and Passau, a hospital in Stühlingen, and many streets across Germany.

Awards and Special Honours

- 1928: Poetry prize from the city of Munich

- 1928: Prize from the city of Eisenach

- 1931: Gottfried Keller Preis

- 1938: Goethe Prize from the City of Frankfurt

- 1939: San Remo Prize

- 1948: Honorary citizen of Passau and Landshut

- 1950: Member of the German Academy for Language and Literature

- 1953: Grand Cross of Merit of the Federal Republic of Germany

- Commemorative plaque for Hans Carossa in Munich

His Books

- Gedichte (1910) - Poems

- Eine Kindheit (1922) - Autobiography, translated as A Childhood

- A Romanian Diary (1924) - About his time as a military doctor in World War I

- Verwandlungen einer Jugend (1928) - Autobiography

- Doctor Gion (1931)

- Führung und Geleit (1933) - Essays

- Geheimnisse des reifen Lebens (1936) - Secrets of Mature Life

- Das Jahr der schönen Täuschungen (1941) - Autobiography

- Der volle Preis (1945) - The Full Price

- Aufzeichnungen aus Italien (1946) - Notes from Italy

- Ungleiche Welten (1951) - Unequal Worlds

- Tagebuch eines jungen Arztes (1955) - Diary of a Young Doctor

See also

In Spanish: Hans Carossa para niños

In Spanish: Hans Carossa para niños