Harry Glicken facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Harry Glicken

|

|

|---|---|

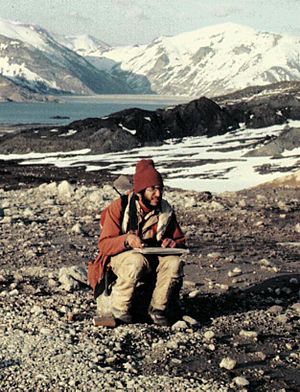

Glicken at work, 1980s

|

|

| Born | March 7, 1958 |

| Died | June 3, 1991 (aged 33) Mount Unzen, Japan 32°45′09.5″N 130°20′14.1″E / 32.752639°N 130.337250°E)

|

| Cause of death | Killed in a pyroclastic flow |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | |

Harry Glicken (March 7, 1958 – June 3, 1991) was an American volcanologist. A volcanologist is a scientist who studies volcanoes. Harry Glicken studied Mount St. Helens in the United States. He worked there before and after its huge eruption in 1980.

Harry was very upset about the death of another volcanologist, David A. Johnston. Johnston was Harry's teacher and boss at Mount St. Helens. Harry was supposed to be at the observation post just before the eruption. But he was called away the night before.

In 1991, Harry was doing research on Mount Unzen in Japan. He was studying avalanches of rock and debris. Sadly, Harry and two other volcanologists, Katia and Maurice Krafft, were killed. They were caught in a pyroclastic flow. This is a super-hot, fast-moving cloud of gas and volcanic rock. Harry's remains were found four days later. He and David Johnston are the only American volcanologists known to have died in volcanic eruptions.

Harry really wanted to work for the United States Geological Survey (USGS). This is a government science agency. But he couldn't get a permanent job there. This was because of a hiring freeze when he finished his PhD. Instead, he got money from groups like the National Science Foundation. This allowed him to become an expert in volcanic debris avalanches. He wrote important papers on this topic. His main paper was about the huge landslide at Mount St. Helens in 1980. This paper made many scientists interested in these types of events.

After his death, Harry's friends published his full report in 1996. Many other studies on debris avalanches have used his work. People who knew Harry praised him for his love of volcanoes. They also admired his strong dedication to his field.

Contents

Harry's Life and Work

Early Years and Mount St. Helens

Harry Glicken was born in 1958. He finished college at Stanford University in 1980. Later that year, he was a student at the University of California, Santa Barbara. The United States Geological Survey (USGS) hired him temporarily. His job was to help watch Mount St. Helens in Washington state. Mount St. Helens had been quiet since the 1840s. But it started to become active again in March 1980.

As the volcano became more active, USGS scientists got ready. They set up observation posts to watch for an eruption. Harry watched the volcano for two weeks. He stayed in a trailer about 5 miles (8 km) from the volcano.

On May 18, 1980, Harry took a day off. He had been working for six days straight. He went to meet his professor, Richard Virgil Fisher, for a school interview. His mentor, David A. Johnston, took his place at the observation post. Johnston was worried about how safe the post was.

A Close Call and a Sad Loss

At 8:32 a.m., a magnitude 5.1 earthquake hit right under the volcano. This caused the north side of the volcano to slide away. Mount St. Helens then erupted. David Johnston was killed instantly. He was caught in fast-moving pyroclastic flows. These flows rushed down the mountain at super-fast speeds.

After the eruption, Harry went to a relief center. He joined a helicopter crew to look for Johnston. They searched for nearly six hours but found nothing. Harry was very upset and couldn't believe Johnston was gone. His friend Don Swanson had to comfort him.

In mid-1980, the USGS decided to create a new observatory. It was named the David A. Johnston Cascades Volcano Observatory (CVO). This observatory would watch volcanoes in Oregon, Washington, and Idaho. Harry went back to Mount St. Helens. He wanted to study what was left after the eruption. But other scientists were already working there.

Instead, Harry worked with Barry Voight, an expert in landslides. Harry focused on his work to help deal with his sadness over Johnston's death. He also hoped to get a job at the USGS. Harry and his team mapped the huge area covered by debris from the volcano's collapse. This debris was about a quarter of the volcano's original size. They carefully studied every piece of debris.

Harry's group created an important study about volcanic landslides. They showed that tall volcanoes often collapse. This study was praised for its new ideas and careful details. It made other volcanologists look for similar debris piles at volcanoes worldwide. Harry became known as the first geologist to explain how these "hummock fields" form near tall volcanoes.

Research After St. Helens and Death

Even though Harry became famous, he still couldn't get a job at the USGS. Some senior scientists found his personality a bit unusual. Activity at Mount St. Helens slowed down. The USGS cut the observatory's budget. Harry kept helping the USGS until 1989. He also worked as a research assistant at the University of California at Santa Barbara.

From 1989 to 1991, Harry continued his volcano studies in Japan. He worked at the Earthquake Research Institute in Tokyo. He got money from the U.S. National Science Foundation. Later, he became a research professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University. There, he started working on Mount Unzen. This volcano had been quiet for 198 years. But it started erupting again in November 1990. The government moved people away from the volcano in May 1991.

On June 2, 1991, Harry visited Mount Unzen with Katia and Maurice Krafft. The next day, they went into a dangerous area near the volcano. They thought that any pyroclastic flows would turn and miss them. But a lava dome collapsed later that day. It sent a large flow down the valley at 60 mph (97 kph). The flow split into two parts. The hotter, upper part reached the scientists' spot, killing them instantly.

In total, 41 or 42 people died in this event. This included reporters who were watching the scientists. The volcano also burned down 390 houses. The flow stretched about 2.5 miles (4 km) long. Harry's remains were found four days later. They were cremated as his parents wished. Harry Glicken and David Johnston are still the only American volcanologists known to have died in a volcanic eruption.

Harry's Posthumous Report

When he died, Harry was trying to publish his main doctoral paper. He had already published parts of it as shorter articles. He had set the rules for finding debris avalanches on volcanoes. Don Swanson called him one of the top experts in this area. After the 1980 Mount St. Helens eruption, more scientists studied debris avalanches. Harry's work on the flows at Mount St. Helens is still seen as the most complete study.

His full report was published in 1996 by his friends. It was called "Rockslide-debris Avalanche of May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens Volcano, Washington". The report included his detailed lab and field work. It also had photos of the eruption. It described Mount St. Helens before the eruption. Jon Major, one of his colleagues, wrote that the Mount St. Helens debris would "never be mapped in such detail again."

Remembering Harry Glicken

Many of Harry's friends thought he had a unique personality. He was chatty and very sensitive. But he also paid very close attention to details. One friend said, "Harry was a character his whole life. ... Everyone who knew him was amazed he was such a good scientist."

Harry's father said in 1991 that his son died doing what he loved. He said Harry was "totally absorbed" in studying volcanoes. Don Peterson, a USGS co-worker, said Harry was very excited about his observations. He praised Harry's achievements as a student and scientist. His mentor, Richard V. Fisher, wrote that what happened at St. Helens "troubled [Glicken] deeply." He thought it made Harry even more dedicated to his work.

Associate Robin Holcomb said Harry was "very enthusiastic, very bright, and very ambitious." Many studies have used Harry's rules for recognizing volcanic landslides. Many papers about avalanches have mentioned his 1996 report. USGS employee Don Swanson called Harry "a world leader in studies of volcanic debris avalanches."

Harry had a strong connection to the University of California, Santa Barbara. He earned his doctorate and did research there. To remember him, the Earth Science Department gives out the "Harry Glicken Memorial Graduate Fellowship" each year. This award helps students who want to study volcanic processes.

Selected Publications

Most of Harry Glicken's published work is about the 1980 eruption of Mount St. Helens. He also wrote papers with other volcanologists about debris avalanches. Colleague Jon Major noted that "The full scope of Harry's work ... has never been published."

- "The 1980 eruptions of Mount St. Helens, Washington". USGS Professional Paper No. 1250 (United States Geological Survey): 347–377. 1981.

- Meyer, William; Sabol, M.A; Glicken, H.X; Voight, Barry (1981). "The effects of ground water, slope stability, and seismic hazards on the stability of the South Fork Castle Creek blockage in the Mount St. Helens area, Washington". USGS Professional Paper No. 1345. Professional Paper (United States Geological Survey). doi:10.3133/pp1345. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/pp1345.

- "The effects of ground water, slope stability, and seismic hazard on the stability of the South Fork Castle Creek blockage in the Mount St. Helens area, Washington". USGS Open File No. 84–624 (United States Geological Survey). 1984.

- Glicken, Harry X.; Meyer, William; Sabol, Martha A. (1989). "Geology and ground-water hydrology of Spirit Lake blockage, Mount St. Helens, Washington, with implications for lake retention". USGS Bulletin No. 1789 (United States Geological Survey). doi:10.3133/b1789. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/b1789.

- Glicken, Harry (1996). "Rockslide-debris avalanche of May 18, 1980, Mount St. Helens Volcano, Washington". USGS Open File No. 96-677. Open-File Report (United States Geological Survey): 98. doi:10.3133/ofr96677. https://pubs.er.usgs.gov/publication/ofr96677.

| Georgia Louise Harris Brown |

| Julian Abele |

| Norma Merrick Sklarek |

| William Sidney Pittman |