HeLa facts for kids

The HeLa cell line is the oldest human cell line used in molecular biology research. Every cell in a cell line has the same genes. Scientists have been using HeLa cells to study cancer, radiation poisoning, and infectious diseases. Like most cancer cells, HeLa cells have more DNA than normal cells.

HeLa cells can also divide forever without help from scientists. Normal, non-cancerous cells can only divide for a little while. This is because their telomeres get too short, and the cell cannot divide anymore. HeLa cells have a special type of active telomerase that keeps their telomeres long during division.

Contents

How HeLa Cells Started

In 1951, these cells were found in a cervical tumor from Henrietta Lacks. She was 30 years old. A doctor named George Gey took a sample of the tumor during Lacks' stay at Johns Hopkins Hospital. He did this without telling her. Henrietta Lacks died later that year. Neither she nor her family were told about the cells until many decades later.

HeLa Cells in Science

HeLa cells have been used for many important discoveries. One famous use was when Jonas Salk used these cells to test his vaccine. This vaccine now protects many people against polio.

More recently, HeLa cells helped Harold zur Hausen create a Human papillomavirus vaccine. He won a Nobel Prize in 2008 for this work. HeLa cells were also important for telomerase research, which won Elizabeth Blackburn a Nobel Prize in 2009. Scientists have also used HeLa cells to develop new chemotherapy treatments for cancer. They also test how nuclear radiation changes cells.

The Discussion Around HeLa Cells

The use of HeLa cells has caused some debate. This is because Henrietta Lacks did not know that a piece of her tumor had been taken. When Lacks was identified nearly twenty years later, it brought up many questions about medical consent. Consent means giving someone permission for something to happen.

Today, there are rules to protect people involved in scientific research. These rules also apply to research samples. Samples can be used as long as the patient's care is good and their identity is kept private. One paper says that if Henrietta Lacks were alive today, doctors might not need to ask for her consent to take the sample.

Some people are still concerned that Henrietta Lacks was not asked for permission. Many modern science methods use DNA sequencing. This means that when experiment results are published, the genetic information of the person whose sample was used can be seen. This is less of a problem when the person's identity is fully protected. But it is troubling in Henrietta Lacks' case. This is because looking at a full genome sequence can show personal information like a person's background and family history.

In 2013, the full genome sequence of the HeLa cell line was made public. This happened without the permission of Lacks' family. Even though parts of the HeLa genome had been sequenced before, it was still possible to find genetic sequences that are often passed down together in families. This could reveal information about Lacks' family. Critics say this was a serious breach of privacy for the Lacks family. Since then, a new National Institutes of Health rule requires researchers to ask for special permission to access the full genome sequence.

Images for kids

-

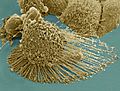

Scanning electron micrograph of an apoptotic HeLa cell. Zeiss Merlin HR-SEM.

-

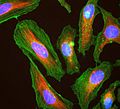

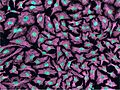

Multiphoton fluorescence image of cultured HeLa cells with a fluorescent protein targeted to the Golgi apparatus (orange), microtubules (green) and counterstained for DNA (cyan). Nikon RTS2000MP custom laser scanning microscope.

-

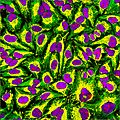

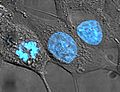

Immunofluorescence of HeLa cells showing microtubules in green, mitochondria in yellow, nucleoli in red and nuclear DNA in purple

-

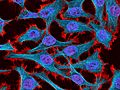

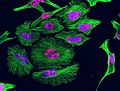

HeLa cells grown in culture and stained with antibody to tubulin (green), antibody to Ki-67 (red) and the blue DNA binding dye DAPI. The tubulin antibody shows the distribution of microtubules and the Ki-67 antibody is expressed in cells about to divide. Preparation, antibodies and image courtesy of EnCor Biotechnology.

-

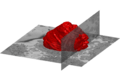

A volumetric surface render (red) of the nuclear envelope of one HeLa cell. The cell was observed in 300 slices of electron microscopy, the nuclear envelope was automatically segmented and rendered. One vertical and one horizontal slice are added for reference.

-

Plasma Membrane and Nuclear Envelope of one Hela Cell displayed as a volumetric surface rendering. Left and centre show the plasma membrane in blue colour with transparency and the nuclear envelope with a solid cyan colour. Right show the plasma membrane without transparency and the same angle of view as the centre. The membranes have been segmented from data acquired with Electron Microscopy.

See also

In Spanish: HeLa para niños

In Spanish: HeLa para niños

| Ernest Everett Just |

| Mary Jackson |

| Emmett Chappelle |

| Marie Maynard Daly |