Henry Ritchie facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Ritchie

|

|

|---|---|

Henry Peel Ritchie VC

|

|

| Born | 29 January 1876 Edinburgh, Scotland |

| Died | 9 December 1958 (aged 82) Edinburgh |

| Buried |

Warriston Crematorium, Edinburgh

|

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ |

|

| Years of service | 1890 – 1917 |

| Rank | Captain |

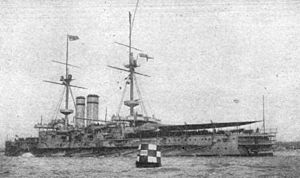

| Unit | HMS Goliath |

| Battles/wars | World War I

|

| Awards | Victoria Cross |

Henry Peel Ritchie (born January 29, 1876 – died December 9, 1958) was a brave officer in the Royal Navy. He received the Victoria Cross (VC), which is the highest award for bravery in the face of the enemy. This medal can be given to members of the British and Commonwealth armed forces.

Ritchie earned the first Victoria Cross given to a naval person during World War I. This was for his actions during a raid on the German port of Dar-es-Salaam in November 1914. He was seriously wounded during this raid.

Even though he was very brave, Ritchie was not immediately put forward for the Victoria Cross. There was a delay because the British Admiralty (the navy's headquarters) discussed which medal he should get. Finally, on April 24, 1915, almost six months later, he received the medal. Ritchie never fully recovered from his injuries. He had to retire early from the navy the next year. He lived for another 41 years but never commanded a ship at sea again.

Contents

Henry Ritchie was born in Edinburgh, Scotland. His parents were Mary Ritchie and Dr. Robert Peel Ritchie. He grew up at 1 Melville Crescent, a nice area in Edinburgh.

Henry went to George Watson's College and Blairlodge School. When he was 14, in 1890, he joined the navy's training ship, HMS Prince of Wales. He quickly moved up in the navy because he was smart and strong. Six years later, he became a lieutenant. For the next 15 years, he worked as a junior officer at the Sheerness Gunnery School.

In 1900, Ritchie became the armed forces lightweight boxing champion. He was also the runner-up the next year. In July 1902, he was sent to the battleship HMS Sans Pareil. This ship was docked in the Medway as part of the Reserve squadron.

While he was stationed at Sheerness, he met and married Christiana Lilian Jardine. They had two daughters together.

His time working on land ended in March 1911. He was then sent to the battleship HMS Goliath as a senior lieutenant. Later that year, he was promoted to commander. He was in charge of the ship's gunnery training and procedures. At this time, Goliath was part of the Channel Fleet in British waters. One of his junior officers said that "Ritchie had the reputation of being very strict, but I always found him most fair."

World War I Service

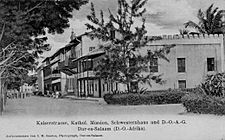

When World War I began, Goliath was sent to the Indian Ocean. Its job was to lead a blockade of German East Africa, a German colony. The main target was the port of Dar-es-Salaam. The British navy was worried that German ships, like the cruisers SMS Emden (1906) and Königsberg, might use these ports. These German ships were known to be in the Indian Ocean.

The concern grew because Königsberg had operated from Dar-es-Salaam. It had even sunk the British cruiser HMS Pegasus. Several German cargo ships were still in Dar-es-Salaam's large natural harbour. These ships could be used to resupply the trapped German cruiser.

Even though the German Governor said the port would not be used for military purposes, the British decided to stop the ships in the port from being used. The Germans had already sunk a ship in the port's entrance channel. This was to stop Goliath and other heavy British warships from entering the harbour. Since they couldn't shell the city from close range, the British put together attack teams. These teams were made up of volunteers from the blockading ships.

Their mission was to make sure the German cargo ships in the port could not be used. Commander Ritchie was given command of this attack. He took two small auxiliary gunboats, Dupleix and Helmuth, to carry his raiding parties.

The Raid on Dar-es-Salaam

The day before the raid, the British decided to warn the Germans. This was to give them time to leave the target ships and avoid injuries. The Germans asked the British to carry out their actions under a white flag, but this was refused. Ritchie was told he could start his attack on the morning of November 28, 1914.

Before reaching the harbour, Dupleix broke down. So, Ritchie had to start his attack with only Helmuth and a few small boats. There were no signs of life on the target ships as Ritchie's boats moved into the port. The shoreline looked "utterly deserted."

Shortly after 10:00 AM, the raiders placed explosives on the abandoned German cargo ships Konig and Feldmarschall. However, the port's commanding officer then challenged them. He questioned their right to be there. He demanded to watch their actions so he could make a report. In a meeting aboard Helmuth, Ritchie explained that British orders were to disable German assets in the harbour. He added that, since they were at war, his permission was not needed.

After some talk, the German officer left. Ritchie then took Helmuth further downriver to look for other ships. But the small ship got stuck on a sandbar. Assuming the way was blocked, he returned to the two cargo ships in a small launch. It was then, while doing a final check, that he found many empty ammunition cases and used bullets in the cargo ships. He realized the German crew had armed themselves before leaving their ships. He suspected they were planning an ambush when his force tried to leave the harbour.

Despite this discovery, Ritchie decided to continue as ordered. He sent Helmuth to the harbour entrance to cover their retreat. He also gathered several small boats in the harbour. He tied these around his launch. This would help his boat stay afloat if it was badly damaged during the fight he expected.

With preparations done, one of Ritchie's boats moved to the harbour entrance. There, it was met with heavy gunfire from the shore. The hidden German crews and town soldiers had been waiting. Helmuth was also attacked. Despite serious damage, both boats managed to get to safety, carrying several wounded men. From outside the harbour, the British ships Fox and Goliath fired back. They destroyed several streets in the town, including the Governor's Palace.

Ritchie, on the only remaining British boat in the harbour, tried to pick up one of his officers. This officer had gone aboard the German hospital ship Tabora for a medical check. This attempt failed. As Ritchie's launch left the harbour, it came under heavy fire from machine guns, rifles, and light artillery.

Most of his crew were wounded. But Ritchie refused to leave his place at the helm (steering wheel) until he had guided his boat to safety. He was found "simply smothered in blood and barely conscious" by Goliath's crew. They went to help him in the battleship's small boat. Ritchie was rushed to the sick bay. It was found that he had been hit in eight different places. The raid cost the British one dead, 14 seriously wounded, and 12 captured. The raiders had stopped three large merchant ships from being used. They also destroyed several buildings on shore and took 35 prisoners.

Two days later, the wounded were in hospital in Zanzibar. Goliath and Fox returned to Dar-es-Salaam. They destroyed most of the seafront and set fire to other parts of the town. This attack made the local people, who had been neutral, turn against the British. Both sides were angry after the raid. The British said that white flags on shore should have stopped any German attack. The Germans said the British tried to capture their merchant crews despite promises not to. It is believed that both sides had planned to break their agreements during the operation.

Retirement and the Victoria Cross

Ten people were honored for their part in the operation. Seven received Distinguished Service Medals. Two received the Conspicuous Gallantry Medal. And one, the badly wounded Ritchie, received the Victoria Cross. Ritchie was not first recommended for this award. The recommendation came later from someone in the Admiralty. Some believe the Admiralty changed its mind to boost morale. However, Ritchie's bravery during the action was never doubted.

The shrapnel and bullet wounds he got in the raid were severe. He had injuries to his forehead, left thumb, left arm (twice), right arm, right hip, and a badly broken right leg from two large machine gun bullets.

Ritchie spent six weeks in hospital in Zanzibar. Then he was well enough to be taken home. In England, he recovered during the spring of 1915 at Plymouth Hospital, with his family. Although he was judged fit in late February, Ritchie was given light duties. He was not sent back to Goliath. This turned out to be lucky for him. Goliath was sunk off the Dardanelles in May 1915 by the Turkish destroyer Muavenet. Five hundred lives were lost.

His Victoria Cross was presented by King George V at Buckingham Palace in April 1915. He was promoted to acting captain. He retired in 1917 because his wounds made him unfit for more service.

After retiring, Ritchie settled with his family back in his home city of Edinburgh. He lived a quiet life. He was not involved in any official way during World War II. He died at his home in 1958. Ritchie was cremated at Warriston. There are no memorials or headstones dedicated to him today. His Victoria Cross is not on public display.

Images for kids

| Isaac Myers |

| D. Hamilton Jackson |

| A. Philip Randolph |