Henry Williamson facts for kids

Quick facts for kids

Henry Williamson

|

|

|---|---|

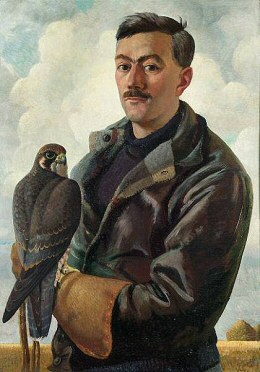

Portrait by Charles Tunnicliffe, c. 1935

|

|

| Born | 1 December 1895 Brockley, London, England

|

| Died | 13 August 1977 (aged 81) Twyford Abbey, London, England

|

| Nationality | English |

| Known for | Nature writing (Tarka the Otter), Ruralist books |

Henry William Williamson (born December 1, 1895 – died August 13, 1977) was an English writer. He wrote many books about wildlife, English history, and country life. He won a special award called the Hawthornden Prize in 1928 for his famous book, Tarka the Otter.

Henry was born in London. He grew up in an area that was still quite natural, which helped him love nature and writing about it. He fought in World War I. After seeing the Christmas truce and the terrible conditions of trench warfare, he wanted to find ways to prevent future wars. He later moved to Devon and became a farmer and writer. He wrote many more novels. Henry was married twice. He passed away in a hospice in London in 1977 and was buried in North Devon.

Contents

Growing Up

Henry Williamson was born in Brockley, a part of south-east London. His father, William Leopold Williamson, worked at a bank. His mother was Gertrude Eliza. When Henry was very young, his family moved to Ladywell. He went to Colfe's School, which was a grammar school. The area where he lived was still quite rural back then. This meant he could easily explore the countryside in Kent. He grew to love nature very much during his childhood.

World War I Experience

On January 22, 1914, Henry Williamson joined the army as a rifleman. He was part of the 5th (City of London) Battalion of the London Regiment. When Germany declared war on August 5, 1914, he was called to serve.

In November 1914, he went to France with his battalion. He entered the trenches on the Western Front near Ypres Salient. There, he saw the famous Christmas truce where British and German soldiers stopped fighting to celebrate Christmas together. In January 1915, he had to leave the trenches because he got trench foot and dysentery. He was sent back to Britain to recover.

After getting better, he became a second lieutenant in the 10th (Service) Battalion of the Bedfordshire Regiment in April 1915. He later joined the Machine Gun Corps in January 1916. In May 1916, he was in the hospital in London due to anaemia and got two months of medical leave. He returned to the Western Front in February 1917. In June 1917, he was gassed while moving supplies to the front line. He was sent back to the UK to recover in military hospitals.

By September 1917, he was assigned to duties away from the front lines because of the effects of the gas. He tried to get back to active fighting, even applying to join the Royal Air Force and the Indian Army. However, his medical condition prevented him. The war ended, and his transfer orders were cancelled. He spent a year helping soldiers leave the army. He was officially discharged from the army on September 19, 1919.

The war deeply affected Williamson. He felt it was pointless and caused by greed. He became determined that Germany and Britain should never fight again. He was also moved by the strong friendships he saw between soldiers from different sides in the trenches.

Starting His Writing Career

Henry wrote about his war experiences in books like The Wet Flanders Plain (1929) and The Patriot's Progress (1930). He also included them in his long series of 15 books called A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight (1951–1969).

After the war, he read a book by Richard Jefferies called The Story of My Heart. This book inspired him to become a serious writer. In 1921, he moved to Georgeham, Devon, and lived in Skirr Cottage. In 1925, he married Ida Loetitia Hibbert. They had six children together. One of their daughters, Margaret, was the first wife of the famous musician Julian Bream.

In 1927, Williamson published his most famous book, Tarka the Otter. This book won him the Hawthornden Prize in 1928. The money he earned from Tarka helped him buy a small wooden hut near Georgeham. He wrote many of his later books there, sometimes spending 15 hours a day alone. This wooden writing hut was later recognized as a historically important building in 2014. Tarka also led to a friendship with T. E. Lawrence, who shared similar ideas about needing lasting peace in Europe.

In 1936, Henry bought a farm in Stiffkey, Norfolk. He wrote about his first years of farming there in his book The Story of a Norfolk Farm (1941).

Life and Writing After the War

After World War II, Henry and his family left the farm. In 1946, Williamson moved to live alone at Ox's Cross, Georgeham in North Devon. He built a small house there just for writing. In 1947, Henry and Loetitia divorced. Henry then married Christine Duffield, a young teacher, in 1949.

He started writing his big series of fifteen novels, A Chronicle of Ancient Sunlight. In 1950, his only child with Christine, Harry Williamson, was born. During this time, Henry also edited a collection of poems and stories by James Farrar, a promising young poet who had died in World War II. From 1951 to 1969, Henry wrote almost one novel each year. He also wrote regularly for newspapers like the Sunday Express and The Sunday Times. In 1968, Christine and Henry divorced.

In 1974, he began working on a script for a film about Tarka the Otter. However, his script was very long and not used for the movie. The film, Tarka the Otter, was released in 1979 and narrated by Peter Ustinov.

Later Years and Death

After a small operation, Henry Williamson's health quickly got worse. One day he was active, and the next he had severe memory loss and didn't recognize his family. He moved into a hospice at Twyford Abbey in Ealing. He passed away there on August 13, 1977. By chance, this was the same day the final scene of the Tarka the Otter film was being shot.

His body was buried in the churchyard of St George's Church, Georgeham, in North Devon. A special service was held in his memory at St Martin-in-the-Fields church. The famous poet Ted Hughes gave a speech there.

Henry Williamson Society

The Henry Williamson Society was started in 1980. This group helps keep his memory and writings alive. His first wife, Loetitia, supported the society until she passed away in 1998. His son, Richard, is now the president of the society.