Tarka the Otter facts for kids

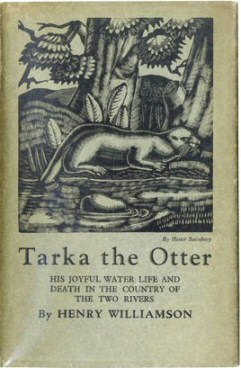

First edition; woodcut after Hester Sainsbury

|

|

| Author | Henry Williamson |

|---|---|

| Country | England |

| Subject | European otter |

| Genre | Natural history novel |

| Publisher | G.P. Putnam's Sons |

|

Publication date

|

1927 |

Tarka the Otter: His Joyful Water-Life and Death in the Country of the Two Rivers is a famous novel written by Henry Williamson. It was first published in 1927. The book won an important award called the Hawthornden Prize in 1928. Since then, it has always been available to read, showing how popular it is.

The story is all about the life of an otter named Tarka. It also gives a lot of details about the places where otters live. These places are in North Devon, England, especially around the River Taw and River Torridge. These two rivers are why the book calls the area "the Country of the Two Rivers." The name "Tarka" means "Wandering as Water," which perfectly describes the otter's journey. Even though some people now see it as a children's book, Tarka has inspired many famous writers like Ted Hughes and Rachel Carson.

Contents

The Story of Tarka the Otter

The book is split into two main parts: "The First Year" and "The Last Year." It tells the exciting journey of Tarka, an otter born in a cozy den by the River Torridge.

Tarka's Early Life and Adventures

Tarka's story begins just before he is born in an otter den, also known as a holt. This holt is near a special water bridge called the Rolle Canal aqueduct. After he is born, Tarka learns how to swim and hunt for food. During this time, he sadly loses one of his brothers or sisters in a trap.

Later, Tarka gets separated from his mother. He then travels all alone across North Devon. His first partner is an older otter named Greymuzzle. Sadly, Greymuzzle is killed during Tarka's first winter, which is very cold and difficult.

Tarka's Family and Main Enemy

In his second year, Tarka has baby otters, called cubs, with his second partner, White-tip. Throughout the book, Williamson shows Tarka's life alongside the local otter hunt. This hunt is Tarka's main enemy. The most important hound in the hunt is a dog named Deadlock. Deadlock is known as the best tracking dog in the "Country of the Two Rivers."

The book ends with a huge, long hunt for Tarka. This hunt lasts for nine hours! It all leads to a final face-off between Tarka and Deadlock.

Places Tarka Explores

Tarka's journey takes him to many real places in Devon. These include Braunton Burrows, the clay pits at Marland, and Morte Point. He also visits Hoar Oak Water and the Chains. The story starts and finishes near the town of Torrington.

How Henry Williamson Wrote the Book

Henry Williamson wrote Tarka the Otter in a very special way. His writing style is often called poetic. This means he used words beautifully, almost like a poem.

A Poetic and Realistic Style

The famous poet Ted Hughes once said that Williamson was "one of the truest English poets of his generation." This shows how much people admired his writing. Williamson's writing is also very realistic. He doesn't make the animals seem too human. He tries to show their natural behaviors and instincts. He avoids making them act or think like people.

Why Tarka the Otter is Important

Even many years after it was written, Tarka the Otter is still a very important book. It has inspired many people and even led to new things in England.

Inspiring Other Writers

The famous nature writer Rachel Carson said that Williamson's books had a "deep influence" on her. She even said that Tarka the Otter would be one of the few books she would take to a desert island! Ted Hughes, another well-known writer, often talked about how important reading Tarka was for him. The author Roger Deakin loved the "beauty and ice-clear accuracy" of Williamson's writing. He called Tarka a "great mythic poem."

Other nature writers, like Kenneth Allsop and Denys Watkins-Pitchford, also found the book very meaningful. Watkins-Pitchford even called it "the greatest animal story ever written."

Tarka's Legacy in Devon

The book has also led to real-world things in Britain. There is now a walking and cycling path called the Tarka Trail in North Devon. The book also helped create the Tarka Country Tourism Authority. This group helps people visit and enjoy the beautiful area where Tarka's story takes place.

Tarka the Otter on Screen and Audio

The story of Tarka has been brought to life in other ways, too!

Audiobook Version

In 1978, the famous naturalist Sir David Attenborough narrated an audiobook version of the story. It was released as a double audio cassette, letting people listen to Tarka's adventures.

Film Adaptation

Tarka the Otter was also made into a movie called Tarka the Otter, which came out in 1979. Henry Williamson himself started working on a script for the film in 1974. He had turned down offers from Walt Disney before. But he finally agreed to let English wildlife filmmaker David Cobham make the movie because he trusted him.

The movie was narrated by Peter Ustinov. The screenplay, or script, was written by Gerald Durrell. Some of Henry Williamson's own family members, his son Richard and daughter-in-law, even appeared in the film! The movie was voted the 98th greatest family film in a Channel 4 poll. The music for the film was created by David Fanshawe and played by Tommy Reilly.

Different Editions of the Book

Tarka the Otter has been published many times over the years. Here are some of the notable editions:

- 1927, UK, G. P. Putnams Sons, Hardback

- 1937, UK, Penguin Books, Paperback

- 1962, UK, Revised edition, Puffin Books, Paperback

- 1965, UK, Bodley Head, Hardback

- 1971, UK, Puffin Books ISBN: 0-14-030060-0, Paperback (C.F. Tunnicliffe, Illustrator)

- 1981, USA, Nelson Thornes ISBN: 0-333-30602-3, Hardcover (C.F. Tunnicliffe, Illustrator)

- 1982, USA, Salem House Publishers ISBN: 0-370-30919-7, Paperback

- 1990, USA, Beacon Press ISBN: 0-8070-8507-3, Paperback (Concord Library Series)

- 1995, UK, Puffin Books ISBN: 0-14-036621-0, Paperback (Annabel Large, Illustrator)

- 2009, UK, Penguin Modern Classics ISBN: 0-141-19035-3, Paperback (Jeremy Gavron, Introduction)

| Bayard Rustin |

| Jeannette Carter |

| Jeremiah A. Brown |